*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 76906 ***

Footnotes have been collected at the end of the text, and are

linked for ease of reference.

Illustrations have been moved to appear at paragraph breaks. Full page

lithographsa and woodcuts were included in the pagination, including

a verso blank page.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

I

II

NICARAGUA;

ITS

PEOPLE, SCENERY, MONUMENTS,

RESOURCES, CONDITION, AND PROPOSED CANAL;

WITH

ONE HUNDRED ORIGINAL MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

By E. G. SQUIER,

FORMERLY CHARGE D’AFFAIRES OF THE UNITED STATES

TO THE REPUBLICS OF CENTRAL AMERICA.

“HIC LOCUS EST GEMINI JANUA VASTA MARIS.”—OVID

A REVISED EDITION

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,

FRANKLIN SQUARE.

1860.

IIIEntered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1860, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court for the Southern District of New York.

v

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I.—The Brig Francis—Departure from New York—San Domingo—The Coast of Central America—Monkey Point—Shrewd Speculations—A Naked Pilot—Almost a Shipwreck—San Juan de Nicaragua—Music of the Chain Cable—A Pompous Official—Delivering a Letter of Introduction—Terra Firma again—“Naguas” and “Guipils”—The Town and its Laguna—Snakes and Alligators—Practical Equality—Celt vs. Negro—A Wan Policeman—The British Consul General for Mosquitia—“Our House” in San Juan—An Emeute—Pigs and Policy—A Viscomte on the Stump—A Serenade—Mosquito Indians—A Picture of Primitive Simplicity, |

17 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER II.—The Port of San Juan de Nicaragua; its Position; Climate; Population; Edifices of its Inhabitants; its Insects; The Nigua; The Scorpion, etc.; its Exports and Imports; Political Condition; Importance, Present and Prospective; Seizure by the English, etc.—Mouth of the River San Juan—The Colorado Mouth—The Tauro—Navigation of the River—Bongos and Piraguas—Los Marineros—Discovery and early History of the Port of San Juan, |

41 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER III.—The Magnates of San Juan—Captain Samuel Shepherd—Royal Grants—Vexatious Delays—Imposing Departure—Entrance of the River San Juan—“Peeling” of the Marineros—Character of the Stream—The Juanillo—An Immemorial Stopping-place—Bongos and their Equipments and Stores—Meals—Esprit du Corps among the Boatmen—The “Oracion”—Queer Caprices—Medio—Our Accommodation—A Specimen Night on the River—Morning Scenes and Impressions—Bongo Life—The Colorado Mouth—Change of Scenery—The Iguana—A Solitary Establishment—Tropical Ease—The Rio Serapiqui—Fight between the Nicaraguans and the English—“A famous victory”—The Rio San Francisco—Remolino Grande—Picturesque River Views—The Hills and Pass of San Carlos—Thunder Storms—The Machuca Rapids—Melchora Indians—Rapids of Mico and Los Valos—Rapids of the Castillo—Island of Bartola—Capture by Lord Nelson—The “Castillo Viejo,” or Old Castle of San Juan—“A Dios California!”—Ascend to the Ruins—Strong Works—Capture of the Fort by the English in 1780—Failure of the Expedition against Nicaragua; a Scrap of History—Passage of the Rapids—Different Aspect of the River—A Black Eagle—Ninety Miles in Six Days—The Port of San Carlos—Great Lake of Nicaragua—Land at San Carlos—The Commandante—Hearty Welcome—Novel Scenes—Ancient Defences—View from the Fort—The Rio Frio—The Gnatosos Indians—A Paradise for Alligators—Some Happy Institutions of theirs, |

55 |

| |

|

| viCHAPTER IV.—San Carlos—Dinner at the Commandante’s—Introduction to “Tortillas y Frijoles”—A Siesta—News of the attempted Revolution—Anticipating Events, and what happened to the Commandante after we left—Departure under a Military Salvo—View of San Carlos from the Lake—Lake Navigation—Card Playing—Gorgeous Sunset—A Midnight Storm—San Migueleto, and the “Bath of the Naides”—Primitive Simplicity—A Day on the Lake—“El Pedernal”—A Bath with Alligators—An “Empacho”—A Trial at Medicine, and great Success—Second Night on the Lake—The Volcanoes of Momobacho, Ometepec, and Madeira—Volcanic Scenery—The Coast of Chontales—The Crew on Politics—“Timbucos” and “Calandracas,” or a Glance at Party Divisions—Arrival at “Los Corals”—Some Account of them—Alarming News—A Council of War—Faith in the United States Flag—The Island of Cuba—More News, and a Return of the “Empacho”—Distant View of Granada—Making a Toilet—Bees—Arrival at the Ruined Fort of Granada—How they Land there—Sensation amongst the Spectators—Entrance to the City—The Abandoned Convent of San Francisco—The Houses of the Inhabitants—First Impressions—Soldiers and Barricades—Thronged Streets—Señor Don Frederico Derbyshire—“Our Host”—A Welcome—Official Courtesies—Our Quarters—First Night in Granada, |

91 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER V.—Reception-Day—General Respect and Admiration for the United States—An Evening Ride—The Plaza—Churches—Hospital—The “Jalteva”—Deserted Municipality—Melancholy Results of Faction—The Arsenal—Natural Defences of the City—“Campo Santo”—An Ex-Director and his “Hacienda”—Shore of the Lake in the Evening—Old Castle—The “Oracion”—An Evening Visit to the Señoritas—Opera amidst Orange Groves—“Alertas” and “Quien Vivas?”—The Granadinas at Home—An Episode on Women and Dress—Mr. Estevens—“Los Malditos Inglesas”—A Female Antiquarian Coadjutor—“Cigaritas”—Indian Girls—Countrymen—An American “Medico”—Native Hospitality to Strangers—The Ways infested by “Facciosos”—An American turned Back—Expected Assault on the City, and Patriotic Resolves “To Die under the American Flag”—A Note on Horses and Saddles—Visit to the Cacao Estates of the Malaccas—The Cacao Tree—Day-Dreams—An Adventure, almost—Grievous Disappointment—Somoza, the Robber Chief—Our Armory—Feverishness of the Public Mind—Life under the Tropics—A Frightened American, who had “seen Somoza,” and his Account of the Interview—Somoza’s Love for the Americans—Good News from Leon—Approach of the General-in-Chief, and an Armed American Escort—Condition of Public Affairs—Proclamation of the Supreme Director—Decrees of the Government—Official Announcements, and Public Addresses—How they Exhibited the Popular Feeling—Nicaraguan Rhetoric—Decisive Measures to put down the Insurgents—General Call to Arms—Martial Law—Publication of a “Banda”—Great Preparations to Receive the General-in-Chief and his “Veteranos”—No further Fear of the “Facciosos”—A Break-neck Ride to the “Laguna de Salinas”—A Volcanic Lake—Descent to the Water—How came Alligators there?—Native “Aguardiente” “not bad to take”—Return to the City—A Religious Procession—The Host—Increasing Tolerance of the People—Preparations for “La Mañana.” |

121 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER VI.—Discovery of Nicaragua in 1522; Gil Gonzales de Avila, and his march into the Country; Lands at Nicoya; Reaches Nicaragua and has an Interview with its Cazique; Is closely questioned; Marches to Dirianga, where he is at first received, but afterwards attacked and forced to retreat; Peculiarities of the Aborigines; Their wealth; Arrival of Francisco Hernandez de Cordova; He subdues the country, and founds the cities of Granada and Leon; Return of Gonzales; Quarrels between the Conquerors; Pedro Arias de Avila, the first Governor of Nicaragua; His death; Is succeeded by Roderigo de Contreras; His son, Hernandez de Contreras, rebels against Spain; Meditates the entire independence of all Spanish America on the Pacific; Succeeds in carrying Nicaragua; Sails for Panama; Captures it; Marches on Nombre de Dios, but dies on the way; Failure of his daring and gigantic Project; Subsequent Incorporation of Nicaragua in the Vice-Royalty of Guatemala—The City of Granada in 1665, by Thomas Gage, an English Monk; Nicaragua called “Mahomet’s Paradise;” The Importance of Granada at that Period; Subsequent Attack by the Pirates, in 1668; Is Burnt; Their Account of it; The Site of Granada; Eligibility of its Position; Population; Commerce; Foreign Merchants; Prospective Importance—Lake Nicaragua; Its Discovery and Exploration; Interesting Account of it by the Chronicler Oviedo, written in 1541; Its Outlet Discovered by Captain Diego Machuca; The wild beasts on its Shores; The Laguna of Songozona; Sharks in the Lake, their Rapacity; Supposed Tides in the Lake; Explanation of the Phenomenon, |

157 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER VII.—Narrative Continued—Arrival of the General-in-Chief—The Army—Fireworks by Daylight—Prisoners—Interview with Gen. Muñoz—Arrival of the Californian Escort—“Piedras Antiguas”—The Stone of the Big Mouth—“El Chiflador”—Other Antiquities—Preparations for Departure—Carts and “Carreteros”—Vexatious Delays—Departure—How I got a Good Horse for a Bad Mule on the Road—Distant View of the Lakes—The Freedom of the Forest—Arrival at Masaya—Grand Entree—Deserted Plaza—A Military Execution—A “Posada”—“Hijos de Washington”—Disappointed Municipality—We escape an Ovation—Road to Nindiri—Apostrophe to Nindiri!—Overtake the Carts—“Alguna Fresca”—Approach the Volcano of Masaya—The “Mal Pais”—Lava Fields—View of the Volcano—Its Eruptions—“El Inferno de Masaya,” the Hell of Masaya—Oviedo’s Account of his Visit to it in 1529—Activity at that Period—The Ascent—The Crater—Superstitions of the Indians—The Old Woman of the Mountain—The Descent of the Fray Blas Castillo into the Crater, |

173 |

| |

|

| viiCHAPTER VIII.—Magnificent Views of Scenery—“Relox del Sol”—John Jones and Antiquities—An “Alarm;” Revolvers and a Rescue—Distant Bells—Don Pedro Blanco—Managua—Another Grand Entree—Our Quarters—Supper Service—Enacting the Lion—Virtues of Aguardiente—An “Obsequio,” or Torch-light Procession in Honor of the United States—A National Anthem—Night with the Fleas—Fourth of July and a Patriotic Breakfast—Saint Jonathan—Leave Managua—Matearas—Privileges of a “Compadre”—Lake of Managua—A magnificent View—The Volcano of Momotombo—A Solitary Ride—Geological Puzzle—Nagarote—The Posada—Mules abandoned—A Sick Californian—Dinner at a Padre’s—The Santa Annita—Virtues of a Piece of Stamped Paper—A Storm in the Forest—Pueblo Nuevo—Five Daughters in Satin Shoes—Unbroken Slumbers—Advance on Leon—Axusco—A Fairy-Glen—The great Plain of Leon—A “touch” of Poetry—Meet the American Consul—A Predicament—Cavalcade of Reception—New Illustration of Republican Simplicity—El Convento—A Metamorphosis—The Bishop of Nicaragua—Forest, Miss Clifton, Mr. Clay—Criticism on Oratory—Nine Volcanoes in a row—Distant View of the Great Cathedral—The City—Imposing Demonstrations—The Grand Plaza—A Pantomimic Speech and Reply—The Ladies, “God bless them!”—House of the American Consul—End of the Ceremonies—Self-congratulations thereon—A Serenade—Martial Aspect of the City—Trouble anticipated—Precautions of the Government, |

201 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER IX.—The City of Leon—Originally built on the Shores of the Lake Managua—Cause of its Removal—Its present Site—Dwellings of its Inhabitants—Style of Building—Devastation of the Civil Wars—Public Buildings—The Great Cathedral—Its Style of Architecture; Interior; Magnificent View from the Roof—The “Cuarto de los Obispos,” or Gallery of the Bishops—The University—The Bishop’s Palace—“Casa del Gobierno”—“Cuartel General”—The Churches of La Merced; Calvario; Recoleccion—Hospital of San Juan de Dios—Stone Bridge—Indian Municipality of Subtiaba—Population of Leon—Predominance of Indian Population—Destruction of Stocks—Mixed Races—Society of Leon—The Females; their Dress—Social Gatherings: the “Tertulia”—How to “break the Ice” and open a Ball—Native Dances—Personal cleanliness of the People—General Temperance—“Aguardiente” and “Italia”—Food—The Tortilla—Frijoles—Plantains—The Markets—Primitive Currency—Meals—Coffee, Chocolate, and “Tiste”—Dulces—Trade of Leon, |

237 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER X.—The Vicinity of Leon—The Bishop’s Baths—Fuenta de Axusco—“Cerro de Los Americanos”—A Military Ball and Civic Dinner—General Guerrero—Official Visit from the Indian Municipality of Subtiaba—Simon Roque—A Secret—Address and Reply—Visit Returned—The Cabildo—An Empty Treasury—“Subtiaba, Leal y Fiel”—Royal Cedulas—Forming a Vocabulary—“Una Decima”—The Indians of Nicaragua; Stature; Complexion; Disposition; Bravery; Industry; Skill in the Arts—Manufacture of Cotton—Primitive Mode of Spinning—Tyrian Purple—Petates and Hammocks—Pottery—“Aguacales,” and “Jicoras”—Costume—Ornaments—Aboriginal Institutions—The Conquest of Nicaragua—Enormities practised toward the Indians—Present Condition of the Indians—The Sequel of Somoza’s Insurrection—Battles of the Obraje and San Jorge—Capture and Execution of Somoza—Moderate Policy of the Government—Return of General Muñoz—Medals—Festival of Peace—Novel Procession—A Black Saint, |

261 |

| |

|

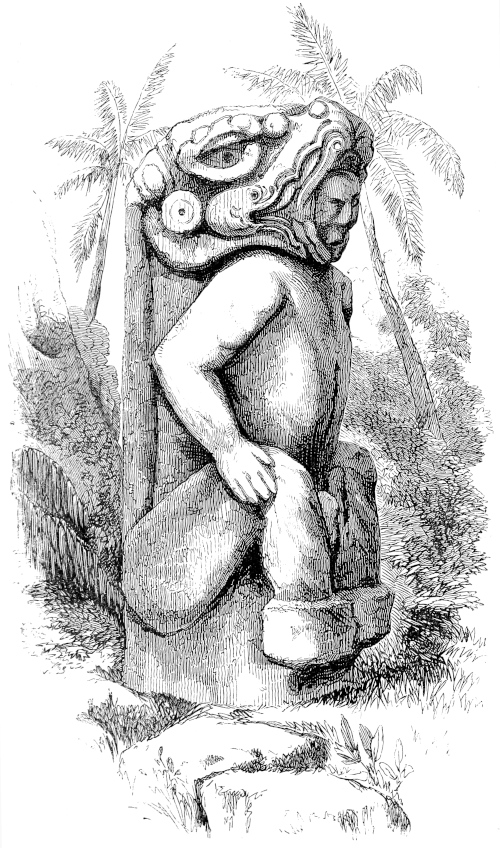

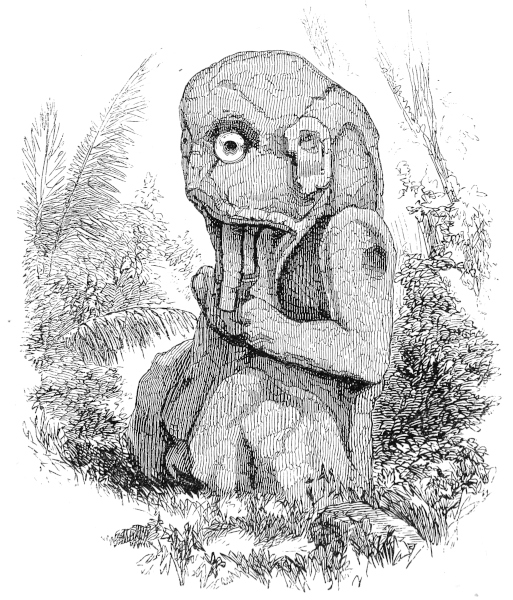

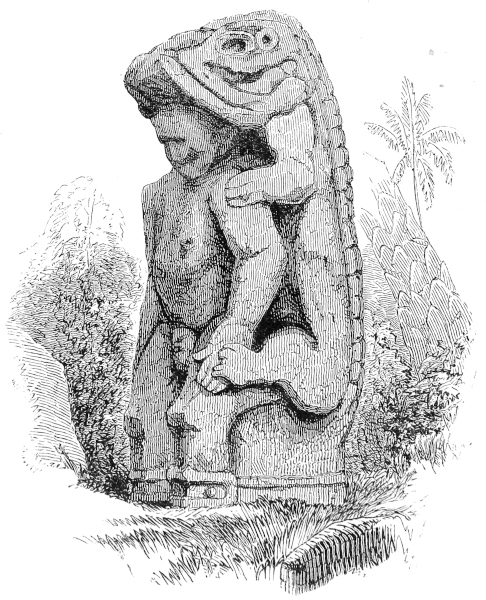

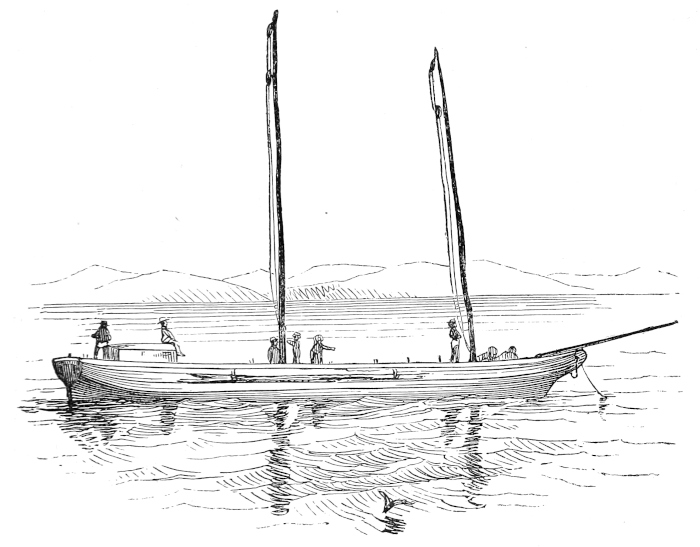

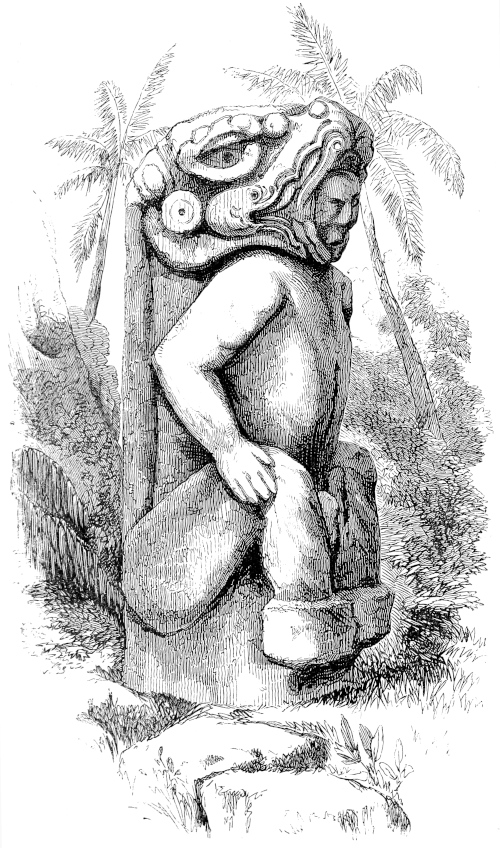

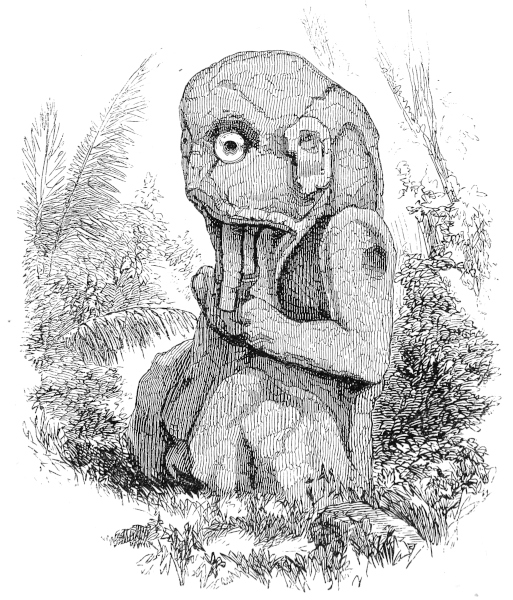

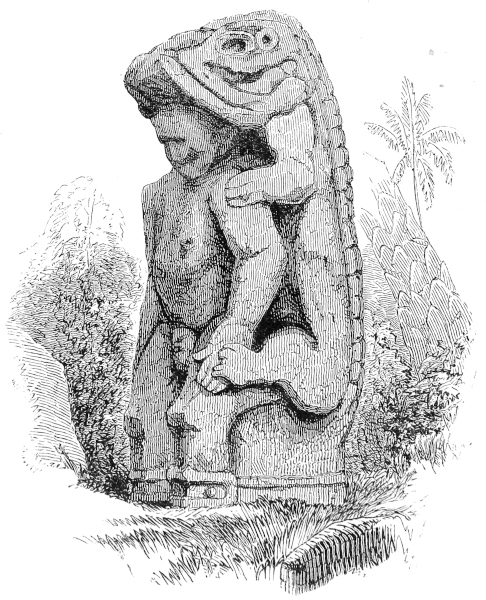

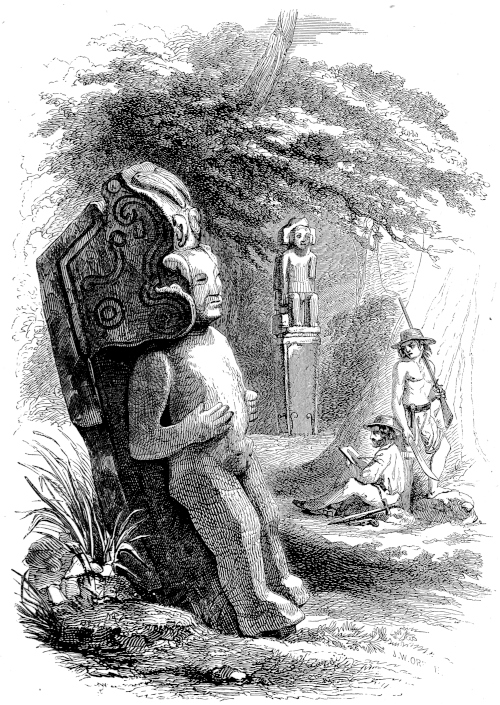

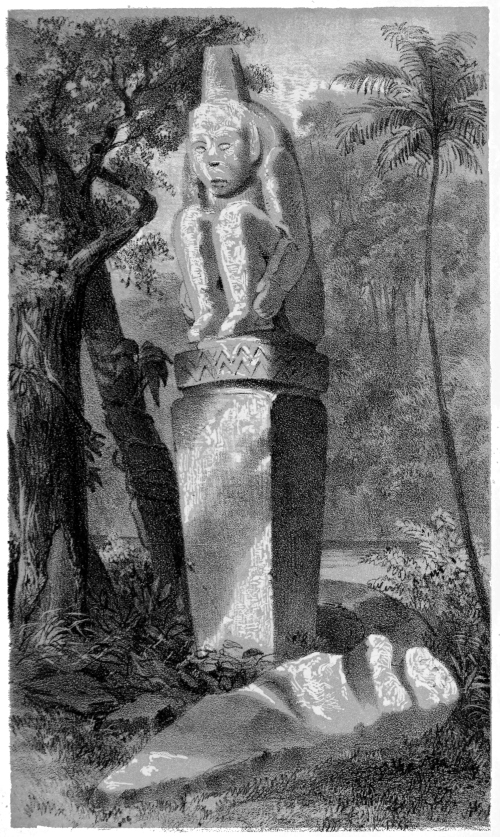

| CHAPTER XI.—Antiquities—Ancient Statue in the Grand Plaza—Monuments on the Island of Momotombita in Lake Managua—Determine to visit them—The Padre Paul—Pueblo Nuevo and our Old Hostess—A Night Ride—“Hacienda de las Vacas”—A Night amongst the “Vaqueros”—The Lake—Our Bongo—Visit the Hot Springs of Momotombo—Attempt to reach one of the “Infernales” of the Volcano—Terrible Heat—Give up the Attempt—Oviedo’s Account of the Volcano—“Punta de los Pajaros”—Momotombita—Dread of Rattlesnakes—The Monuments—Resolve to remove the largest—A Nest of Scorpions—Tribulation of our Crew—Hard Work—How to ship an Idol—Virtues of Aguardiente—“Purchasing an Elephant”—More “Piedras Antiguas”—The Island once Inhabited—Supposed Causeway to the Main-land—A Perilous Night Voyage—Difficult Landing—Alacran, or Scorpion Dance—A Foot-march in the Forest—The “Hacienda de los Vacas” again—Scant Supper—Return to Leon—The Idol sent, via Cape Horn, to Washington—A Satisfied Padre—Idols from Subtiaba—Monstrous Heads—Visit to an Ancient Temple—Fragments—More Idols—Indian Superstitions—“El Toro”—Lightning on Two Legs—A Chase after Horses—Sweet Revenge—“Capilla de la Piedra”—Place of the Idol—The Fray Francisco de Bobadilla—How he Converted the Indians—Probable History of my Idols—The Ancient Church “La Mercedes de Subtiaba”—Its Ruins—“Agarrapatas”—Tropical Insects—Snakes and Scorpions versus Fleas and Wood-ticks—A Choice of Evils, |

285 |

| |

|

| viiiCHAPTER XII.—Amusements in Leon—Cock Fighting—“Patio de Los Gallos”—Decline of the Cock-pit—Gaming—Bull Baiting—Novel Riding—“Una Sagrada Funcion,” or Mystery—A Poem, and a Drama—“Una Compania de Funambulos,” or Rope Dancers—Great Anticipations—A Novel Theatre—The Performance—“La Jovena Catalina” and the “Eccentric Clown, Simon”—“Tobillos Gruesos,” or “Big Ankles”—“Fiestas,“ and Saints’ Days—The “Fiesta” of St. Andrew—Dance of the Devils—Unearthly Music—All-Saints’ Day—A Carnival in Subtiaba—An Abrupt Conclusion, |

313 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XIII.—A Sortie from Leon—Quesalguaque—El Estero de Doña Paula—The “Monte de San Juan”—Summary way of disposing of “Ladrones”—“El Tigre,” Jaguar, or Ounce, Its Habits; How Hunted—The “Lion,” or Puma—The “Coyote”—Posultega—A Specimen Padre—Sobrinas—Chichigalpa—Poised Thunder-storm—The Oracion—Hacienda of San Antonio—Chinandega—A Challenge—El Viejo—Familiar Fixtures—An Enterprizing Citizen and his Tragic Fate—A Decaying Town—Horses vs. Mules—Visit to the Haciendas—An Indigo Estate, and a Mayor Domo—Fine View—The Sugar Estate of San Geronimo—Bachelor Quarters and Hacienda Life—A Fruit Garden—The Bread-Fruit—Sugar-mills, and the Manufacture of Aguardiente—A Sinful Siesta—Visit From the Municipality—“Una Cancion”—Chinandega by Daylight—Realejo—Port and Harbor—The Progress of Enterprize—The Projected New Town of Corinth—Return to Leon, |

329 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XIV.—The Priesthood in Nicaragua—Decline in the Influence of the Church—-Banishment of the Archbishop—Suppression of the Convents—Prohibition of Papal Bulls—Legitimization of the Children of Priests—The Three Abandoned Convents of Leon—Padre Cartine, the last of the Franciscans—Reception, or Clock-room—The Padre’s Pets; His Oratory; Private Apartments; Workshop—A Skull and its History—The Eglesia del Recoleccion—The Padre as a Landlord; As a Painter; As an Uncle; And as Negociator in Marriage—An Auspicious Omen—Death of the Vicar of the Diocess of Nicaragua—His Obsequies—A Funeral Oration—Priestly Eloquence—An Epitaph—General Funeral Ceremonies—Death as an Angel of Mercy—Burial Practices—Capellanias; Their Effects, and the Policy of the Government in Respect to them—Popular Bigotry and Superstition—An Ancient Indulgence—The Potency of an Ejaculation—Remission of Sins—Penetencias—Rationale of the Practice—Novel Penances—Turning Sins to Good Account—Good from Evil—System of the Padre Cartine—The Diocess of Nicaragua, and its Bishop—General Education—Public Schools—The Universities of Leon and Granada—A Sad Picture, |

355 |

| |

|

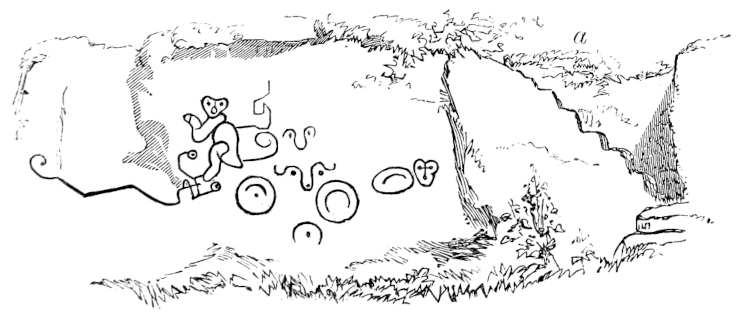

| CHAPTER XV.—Visits to the capital City, Managua—Legislative Assembly; How to procure a Quorum—Executive Message—Ratification of Treaty with the United States—Antiquities—Lake of Nihapa—Huertas—Dividing Ridge—Traces of Volcanic Action—Hacienda de Ganado—An Extensive Prospect—Extinct Crater—Ancient Paintings on the Cliffs—Symbolical Feathered Serpent—A Natural Temple—Superstitions of the Indians—Salt Lake—Laguna de Las Lavadoras—A Courier—Three Months Later from Home—The Shore of Lake Managua—Aboriginal Fisheries—Ancient Carving—Population of Managua—Resources of surrounding Country—Coffee—Inhabitants—Visit Tipitapa—Sunrise on the Lake—Hot Springs—Outlet of Lake—Mud and Alligators—Dry Channel—Village of Tipitapa—Surly Host—Salto de Tipitapa—Hot Springs again—Stone Bridge—Face of the Country—Nicaragua or Brazil Wood—Estate of Pasquel—Practical Communism—Matapalo or Kill-tree—Landing and Estero of Pasquel or Panaloya—Return—Depth of Lake Managua—Communication between the two Lakes—Popular Errors, |

383 |

| |

|

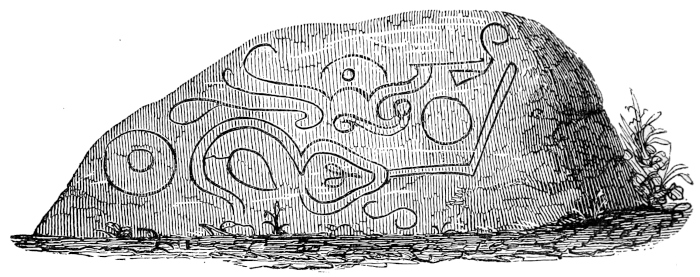

| CHAPTER XVI.—Second Antiquarian Expedition—The Shores of Lake Managua once more—Matearas—Don Henrique’s Comadre—I am engaged as Godfather—An Amazon—Santa Maria de Buena Vista—A “Character” in Petticoats—“La Negrita y La Blanquita”—Purchase of Buena Vista—A Yankee Idea in a Nicaraguan Head—Hints for Speculators—Muchacho vs. Burro—Equestrian Intoxication—Another Apostrophe!—Pescadors—“Hay no mas,” and “Esta aqui,” as Measures of Distance—Managua—The “Malpais,” Nindiri and Masaya—Something Cool—A Pompous Alcalde—How to Arrest Conspirators—Flowers of the Palm—Descent to the Lake—Memorials of Catastrophes—Las Aguadoras—New Mode of Sounding Depths—Ill-bred Monkeys—Traditional Practices—Oviedo’s Account of the Lake in 1529—Sardines—The Plaza on Market Night—A Yankee Clock—Something Cooler—A State Bedroom for a Minister—Ancient Church—Filling out a Vocabulary—“Quebrada de las Inscripciones”—Sculptured Rocks—Their Character—Ancient Excavations in the Rock—“El Baño”—Painted Rocks of Santa Catarina—Night Ride to Granada—The Laguna de Salinas by Moonlight—Granada in Peace—A Query Touching Human Happiness—New Quarters and Old Friends—An American Sailor—His Adventures—“Win or Die”—A Happy Sequel, |

413 |

| |

|

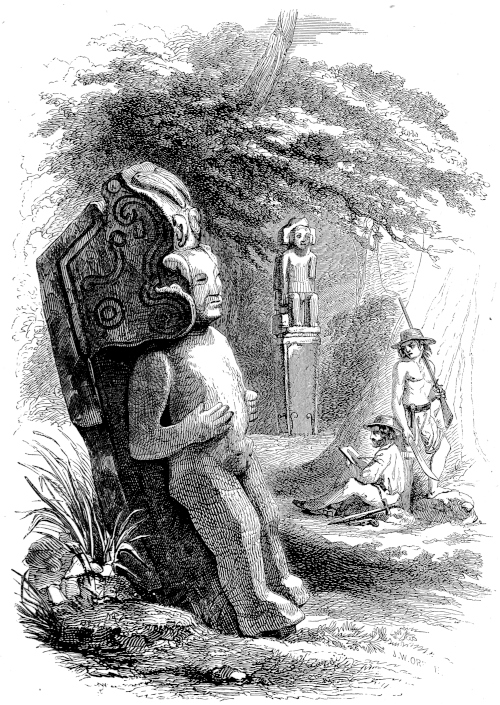

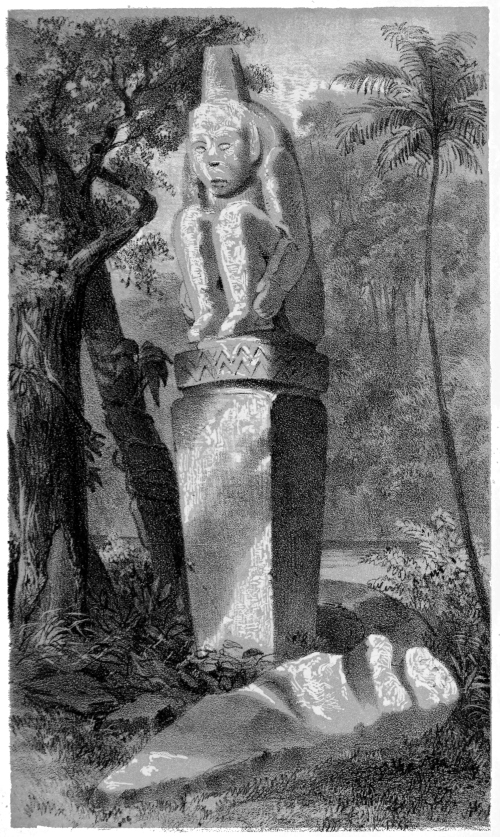

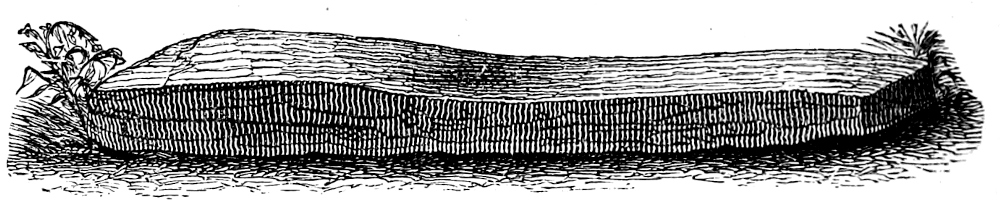

| ixCHAPTER XVII.—Visit to Pensacola—Discovery of Monuments—Search for others—Success—Departure for “El Zapatero”—La Carlota—Los Corales—Isla de La Santa Rosa—A Night Voyage—Arrival at Zapatero—Search for Monuments—False Alarm—Discovery of Statues—Indians from Ometepec—A Strong Force—Further Investigations—Mad Dance—Extinct Crater and Volcanic Lake—Stone of Sacrifice—El Canon—Description of Monuments, and their probable Origin—Life on the Island, |

447 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XVIII.—Return to Granada—A Ball in Honor of “El Ministro”—The Funambulos—Departure for Rivas or Nicaragua—Hills of Scoriæ—The Insane Girl and the Brown Samaritan—A Way-side Idol—Mountain Lakes and Strange Birds—A Sudden Storm—Take Refuge among the “Vaqueros”—Inhospitable Reception—Night Ride; Darkness and Storm—Friendly Indians—Indian Pueblo of Nandyme—The Hacienda of Jesus Maria—An Astonished Mayor Domo—How to get a Supper—Jicorales—Ochomogo—Rio Gil Gonzales—The “Obraje”—Rivas and its Dependencies—Señor Hurtado—His Cacao Plantation—The City—Effect of Earthquakes and of Shot—Attack of Somoza—Another American—His attempt to cultivate Cotton on the Island of Ometepec—Murder of his Wife—Failure of his Enterprize—A Word about Cotton Policy—The Antiquities of Ometepec—Aboriginal Burial Places—Funeral Vases—Relics of Metal—Golden Idols—A Copper Mask—Antique Pottery—A Frog in Verd Antique—Sickness of my Companions—The Pueblo of San Jorge—Shore of the Lake—Feats of Horsemanship—Lance Practice—Visit Potosi—Another Remarkable Relic of Aboriginal Superstition—The Valley of Brito—An Indigo Estate—Cultivation of Indigo—Village of Brito—A Decaying Family and a Decayed Estate—An Ancient Vase—Observations on the Proposed Canal—Return alone to Granada—Despatches—A forced March to Leon, |

491 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XIX.—Volcanoes of Central America; their Number—Volcano of Jorullo—Isalco—The Volcanic Chain of the Marabios—Infernales—“La Baila de Los Demonios”—Volcanic Outburst on the Plain of Leon—Visit to the New Volcano, and Narrow Escape—Baptizing a Volcano—Eruption of Coseguina—Celebration of its Anniversary—Synchronous Earthquakes—Late Earthquakes in Central America—Volcano of Telica—El Volcan Viejo—Subterranean Lava Beds—Activity of the Volcanoes of the Marabios in the 16th Century—The Phenomena of Earthquakes—Earthquake of Oct. 27, 1849—Volcanic Features of the Country—Extinct Craters—Volcanic Lakes—The Volcano of Nindiri or Masaya—Descent into it by the Fray Blas de Castillo—Extraordinary Description, |

525 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XX.—Christmas—Nacimientos—The Cathedral on Christmas Eve—Midnight Ceremonies—An Alarm—Attempt at Revolution—Fight in the Plaza—Triumph of Order—The Dead—Melancholy Scenes—A Scheme of Federation, |

551 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXI.—The “Paseo al Mar”—Preparations for the Annual Visit to the Sea—The Migration—Impromptu Dwellings—Indian Potters—The Salines—The Encampment—First Impressions—Contrabanda—Old Friends—The Camp by Moonlight—Practical Jokes—A Brief Alarm—Dance on the Shore—Un Juego—Lodgings, Cheap and Romantic—An Ocean Lullaby—Morning—Sea Bathing—Routine of the Paseo—Divertisements—Return to Leon, |

561 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXII.—Proposed Visit to San Salvador and Honduras—Departure from |

| Leon—ChinandegaLeon—Chinandega—Ladrones—The Goitre—Gigantic Forest Trees—Port of Tempisque—The Estero Real and its Scenery—A novel Custom house and its Commandante—Night on the Estero—Bay of Fonseca—Volcano of Conseguina—The Island of Tigre—Port of Amapala—View from the Island—Entrance to the Bay—Sacate Grande—Exciting News from Honduras—English Fortifications—Extent, Resources, and Importance of the Bay—Departure for the Seat of War, |

575 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXIII.—Departure for San Lorenzo—Morning Scenes—Novel Cavalcade—A High Plain—Life amongst Revolutions—Nacaome—Military Reception—General Cabañas—An Alarm—Negotiations—British Interference—A Truce—Prospects of Adjustment—An Evening Review—The Soldiery—A Night Ride—Return to San Lorenzo, |

595 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXIV.—La Union—Oysters—American Books—Chiquirin—French Frigate “La Serieuse”—Admiral Hornby of the Asia, 84—French and English war Vessels—Ascent of the Volcano of Conchagua—A Mountain Village—Peculiarities of the Indians—Las Tortilleras—Volcano of San Miguel—Fir Forests—An Ancient Volcano Vent—The Crater of Conchagua—Peak of Scoriæ—View from the Volcano—Enveloped in Clouds—Perilous Descent—Yololtoca—Pueblo of Conchagua again—An Obsequio—Indian Welcome—Semana Santa—Devils—Surrender of Guardiola—San Salvador—Its Condition and Relations, |

613 |

| x |

|

| CHAPTER XXV.—Departure for the United States—An American Hotel in Granada—Los Cocos—Voyage through the Lake—Descent of the River—San Juan—Chagres—Home—Outline of Nicaraguan Constitution—Conclusion of Narrative, |

633 |

| |

|

| APPENDIX. |

| |

|

| CHAPTER I.—General Account of Nicaragua; its Boundaries, Topography, Lakes, Rivers, Ports, Climate, Population, Productions, Mines, etc., etc., |

639 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER II.—The Proposed Inter-Oceanic Canal; Early Explorations; Survey of Colonel Childs in 1851; Various Lines proposed from Lake Nicaragua to the Pacific, etc., etc., |

657 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER III.—Outline of Negotiations in respect to the Proposed Canal, etc., etc. |

672 |

xi

ILLUSTRATIONS.

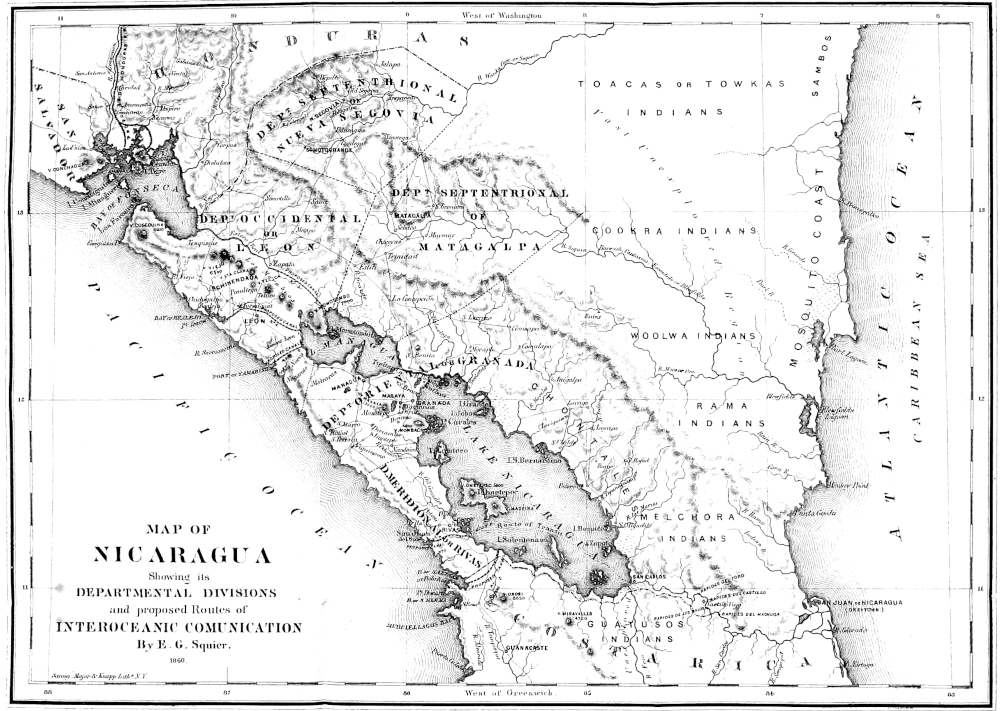

| MAP. |

| General Map of Nicaragua. |

|

| |

|

| LITHOGRAPHS. |

| |

PAGE |

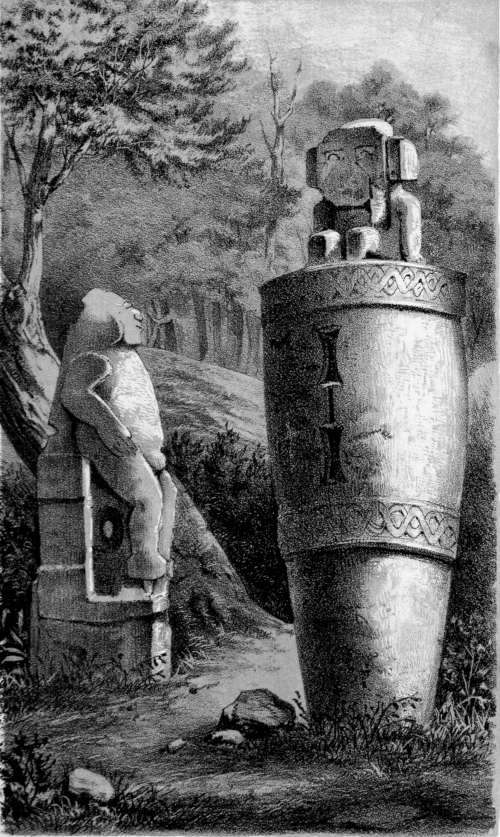

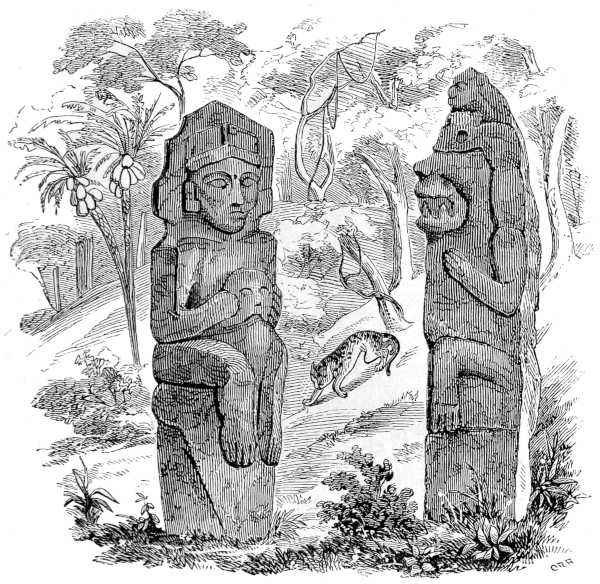

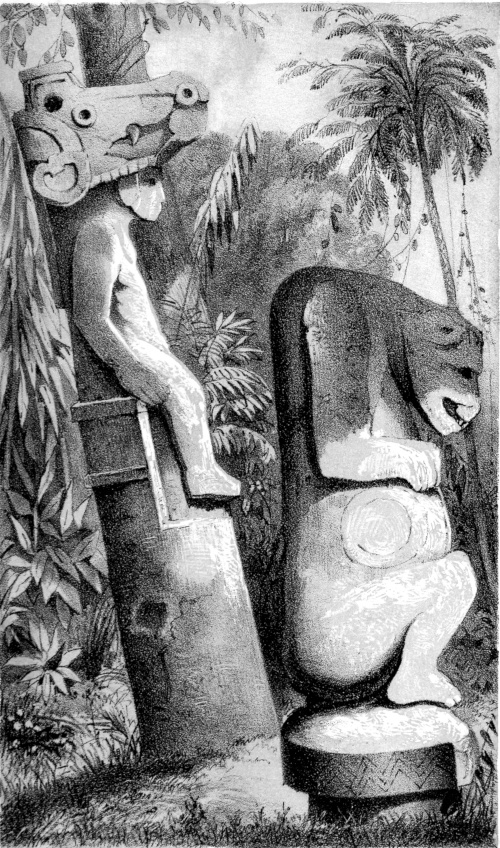

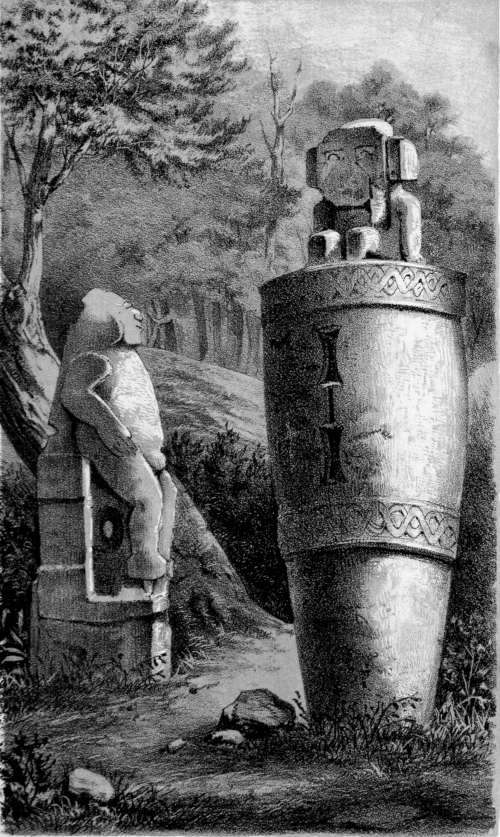

| 1—Idols at Zapatero, Nos. 2 and 3, |

Facing 474 |

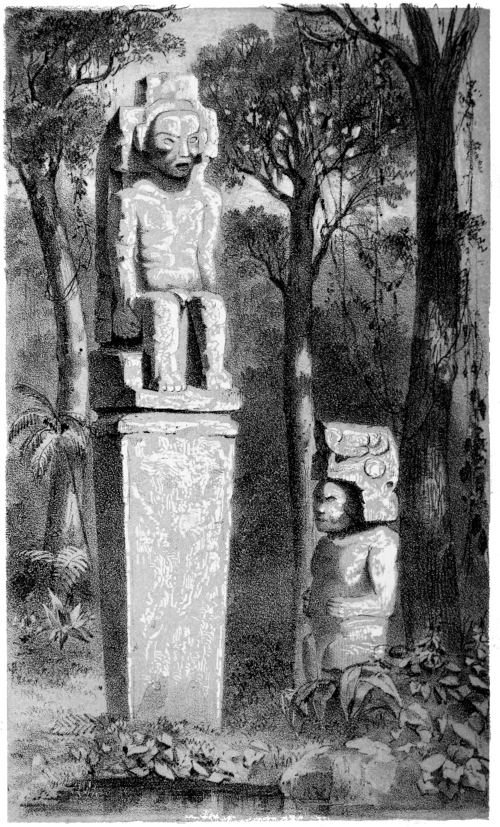

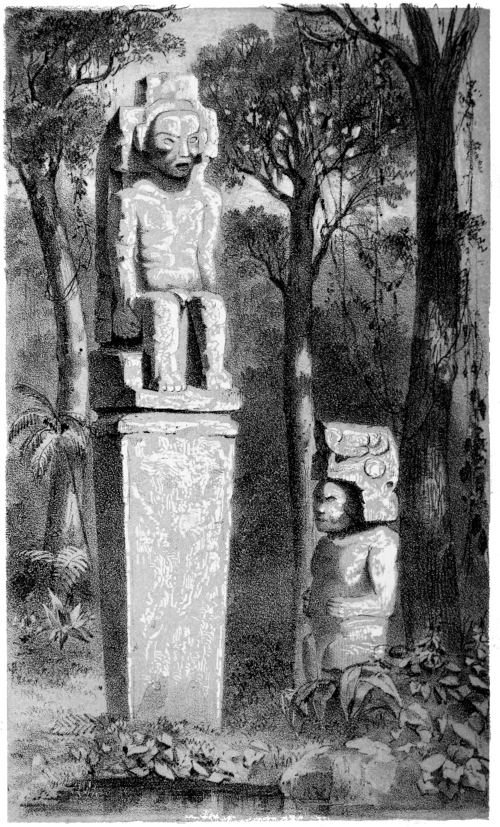

| 2—Idols at Zapatero, Nos. 4 and 5, |

” 478 |

| 3—Idols at Zapatero, Nos. 6 and 7, |

” 479 |

| 4—Idols at Zapatero, Nos. 15 and 16, |

” 486 |

| |

|

| WOOD ENGRAVINGS. |

| |

|

| 1—Arms of Nicaragua, |

Title. |

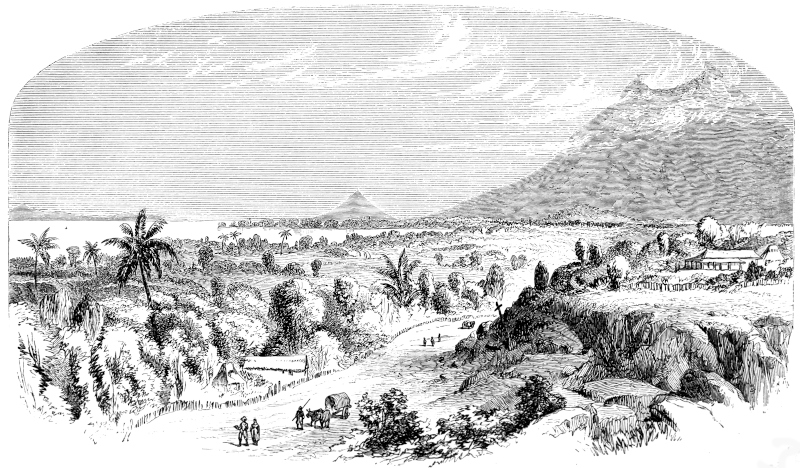

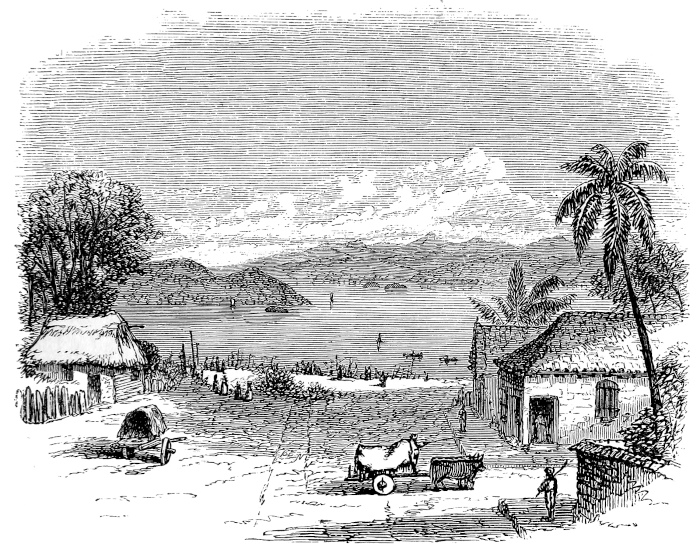

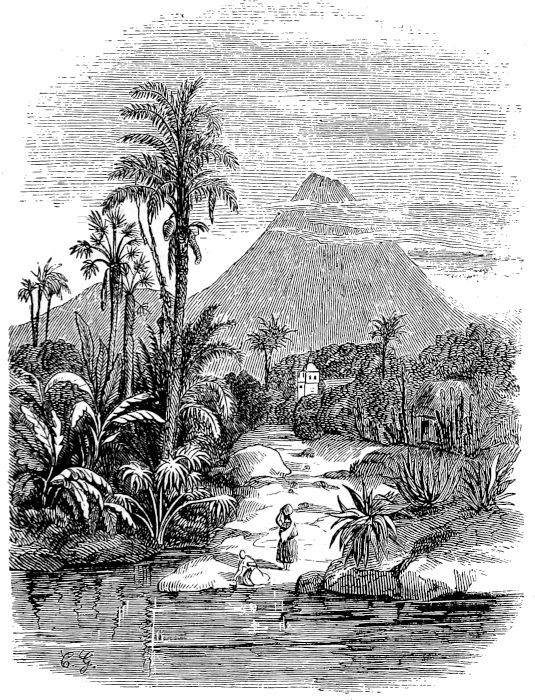

| 2—View of Lake Nicaragua, from the Sandoval Hacienda, near Granada, |

Frontispiece. |

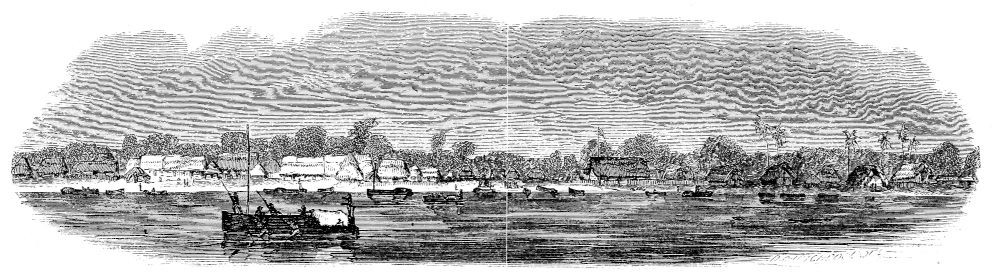

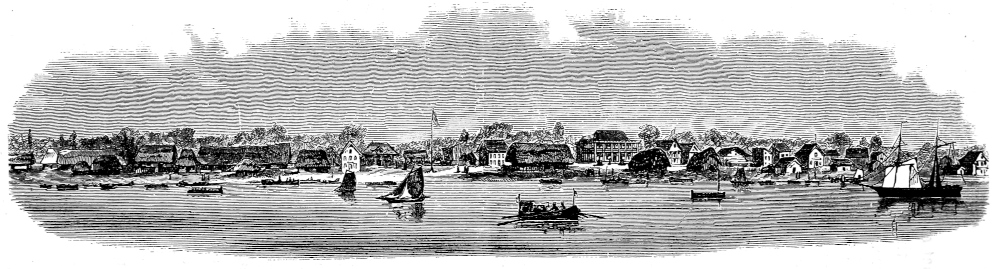

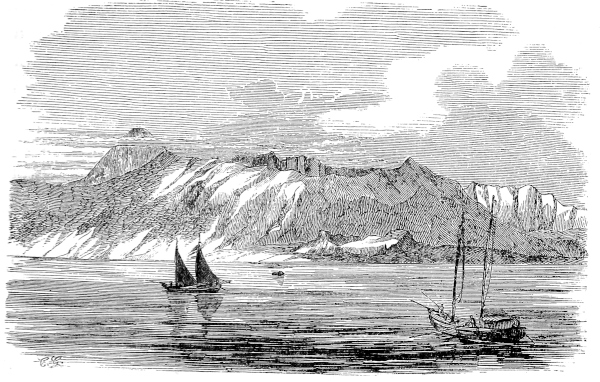

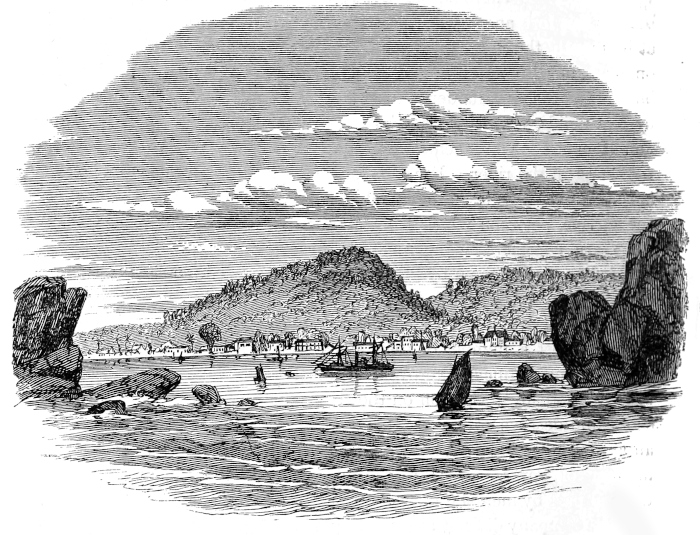

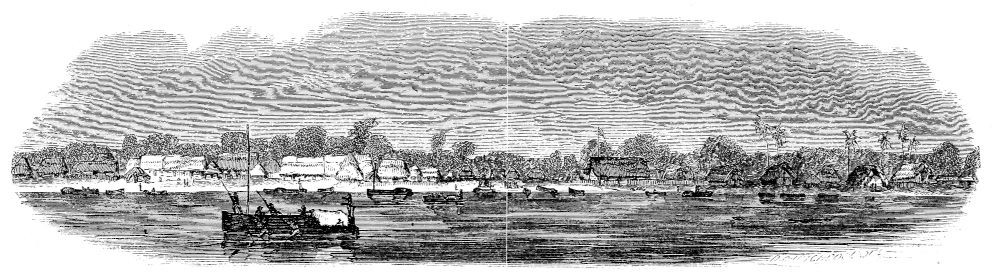

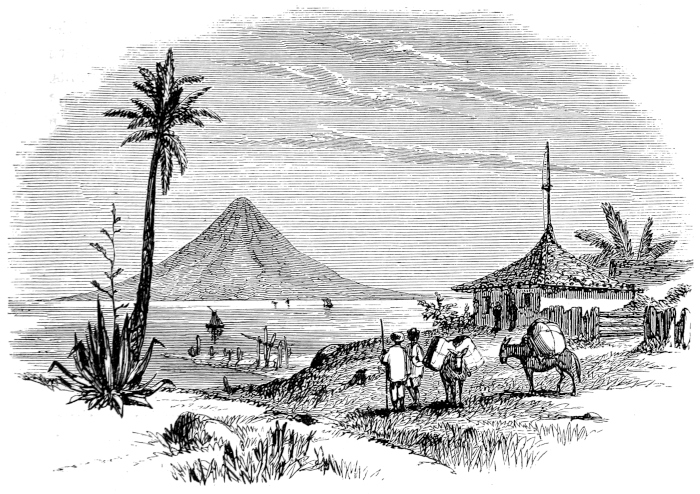

| 3—San Juan de Nicaragua, 1849, |

25 |

| 4—“Our House,” San Juan, |

35 |

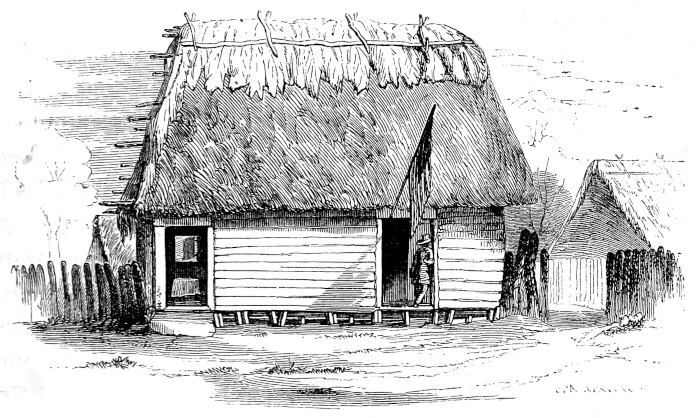

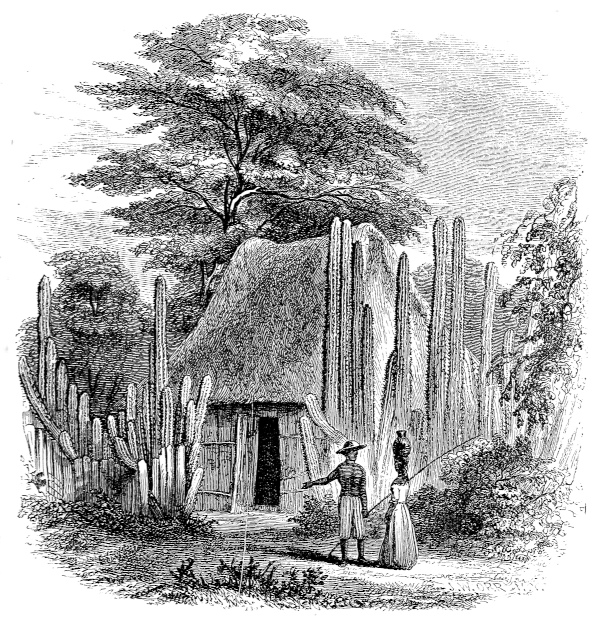

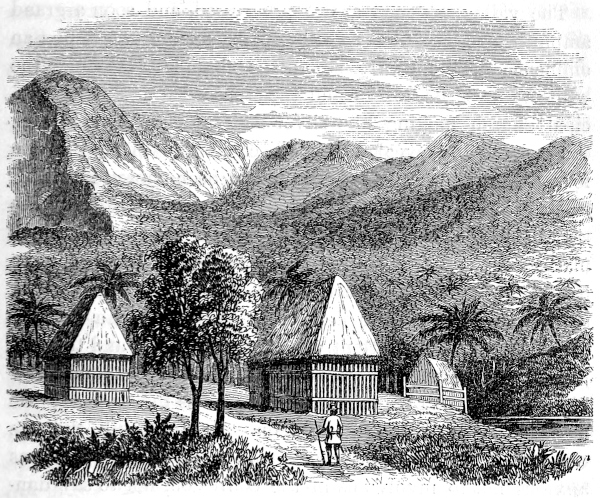

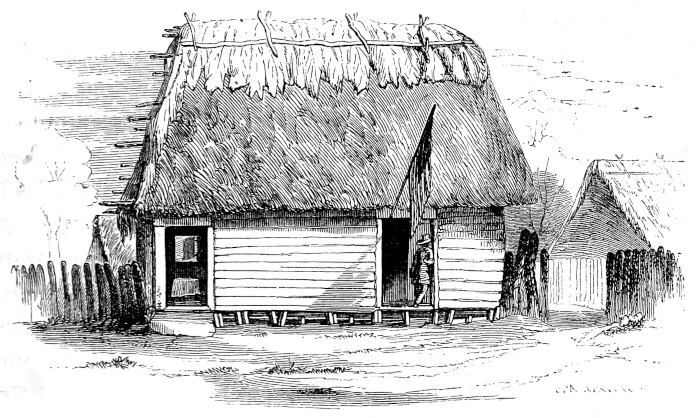

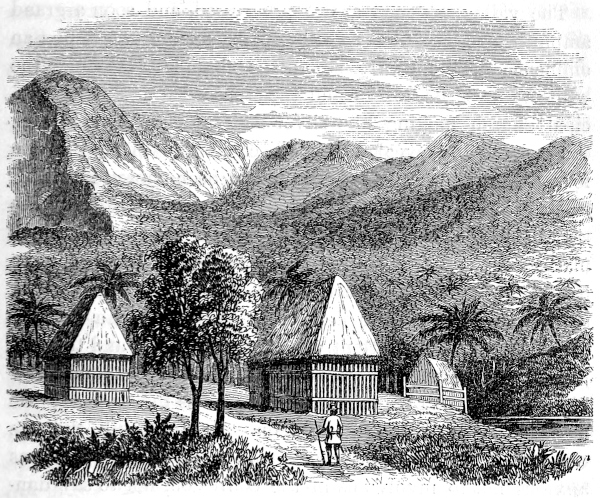

| 5—Hut of Mosquito Indians, |

39 |

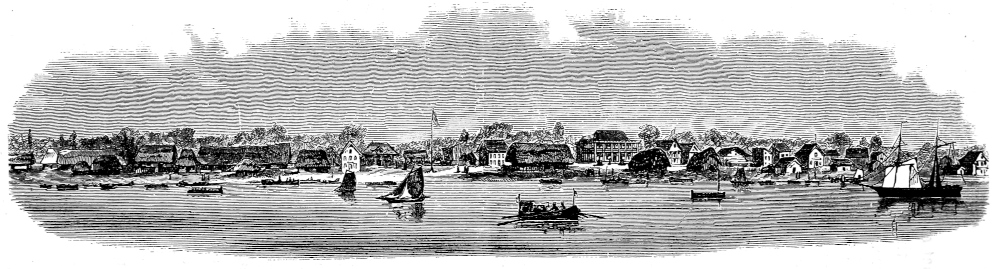

| 6—San Juan de Nicaragua, 1853, |

54 |

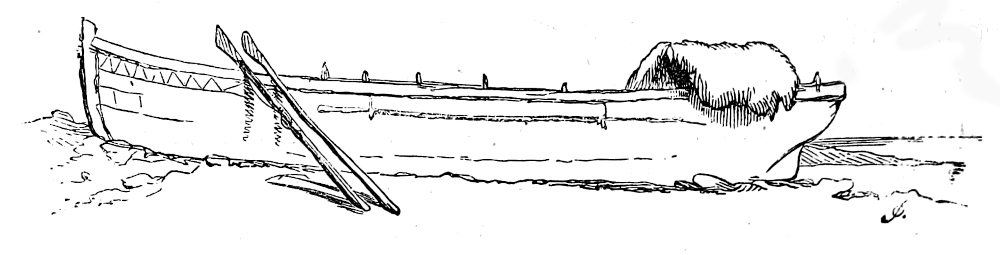

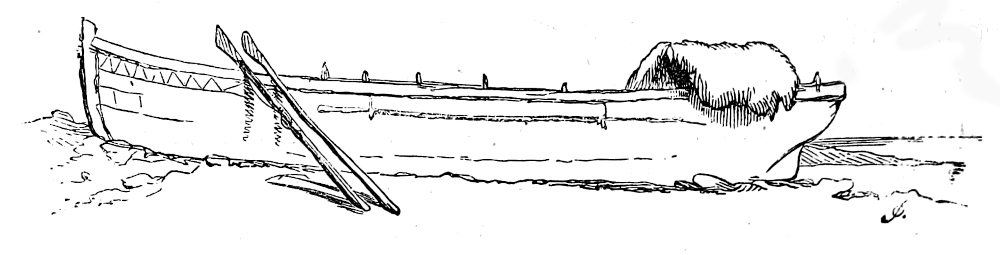

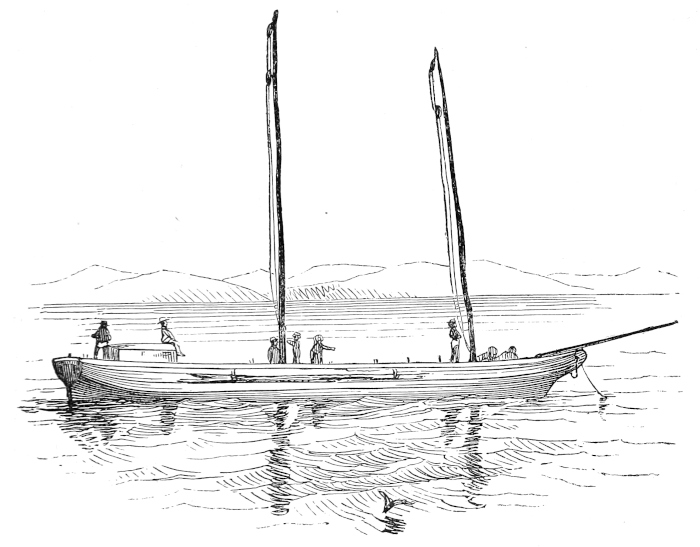

| 7—The Bongo “La Granadina,” |

60 |

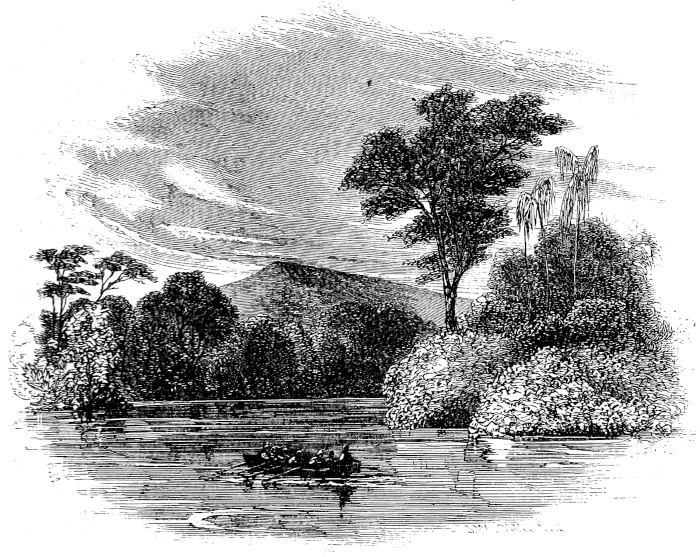

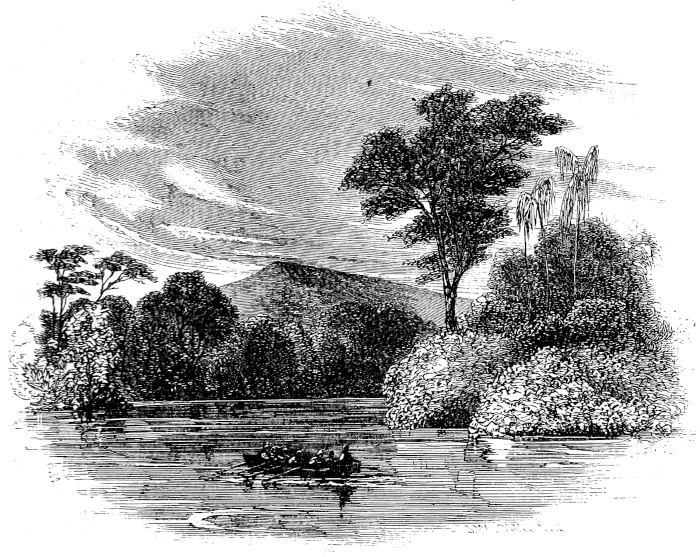

| 8—View on San Juan River, |

73 |

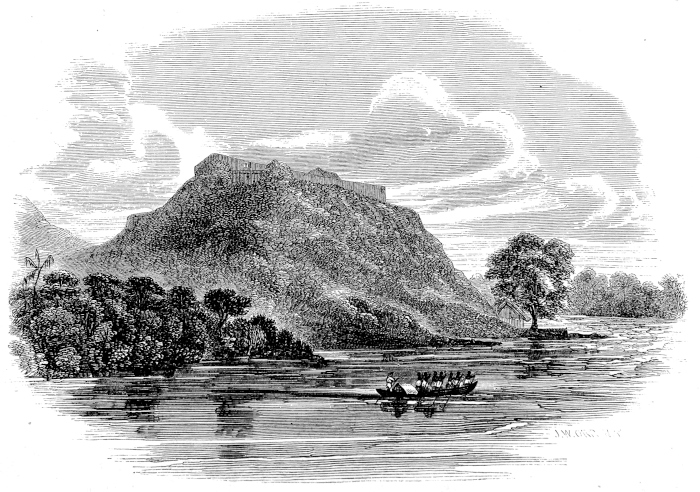

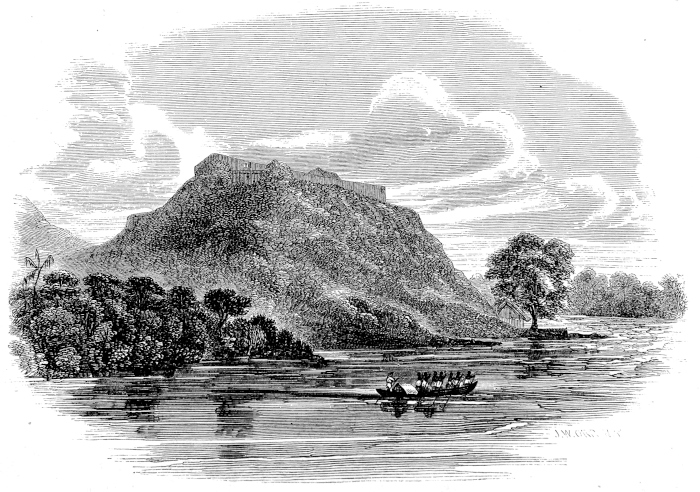

| 9—El Castillo Viejo, or Old Fort, |

77 |

| 10—Sentinel’s Box at El Castillo, |

82 |

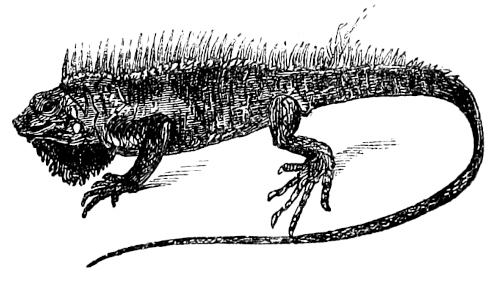

| 11—The Iguana, |

90 |

| 12—Fort of San Carlos, |

95 |

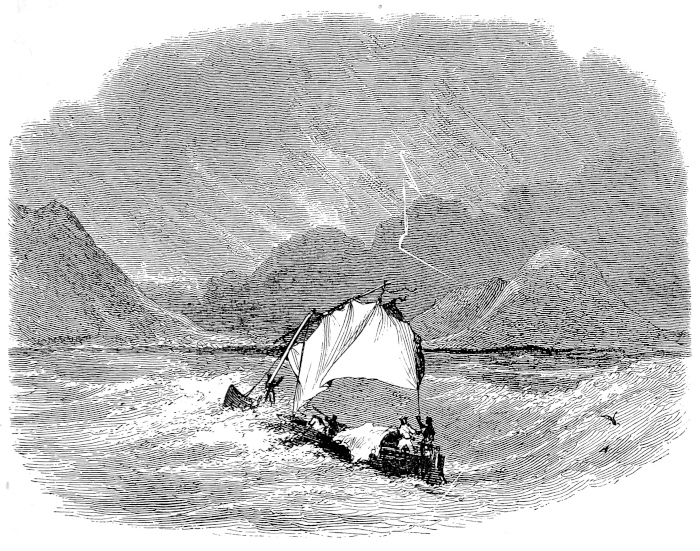

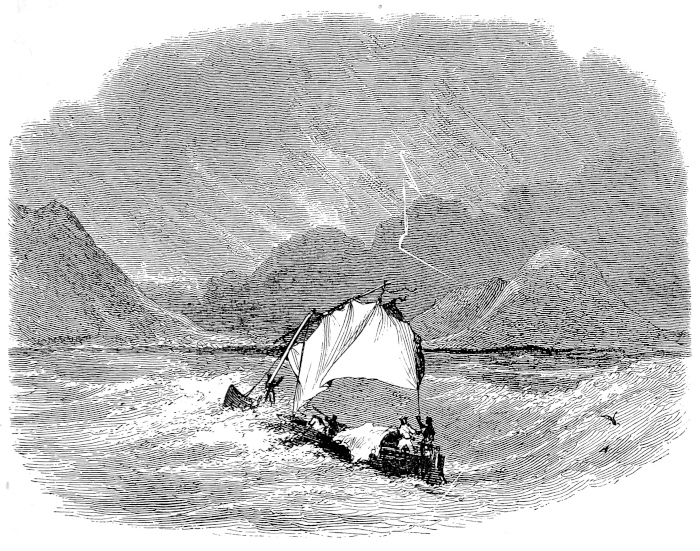

| 13—Storm on Lake Nicaragua, |

99 |

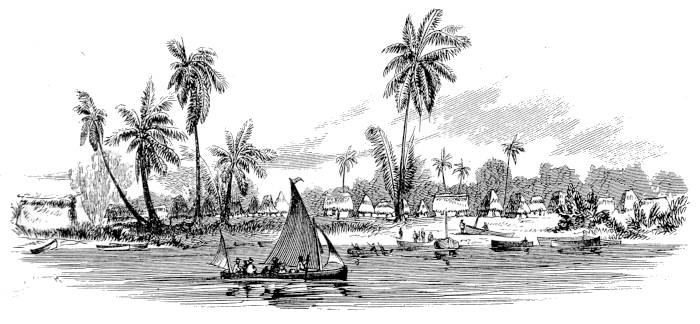

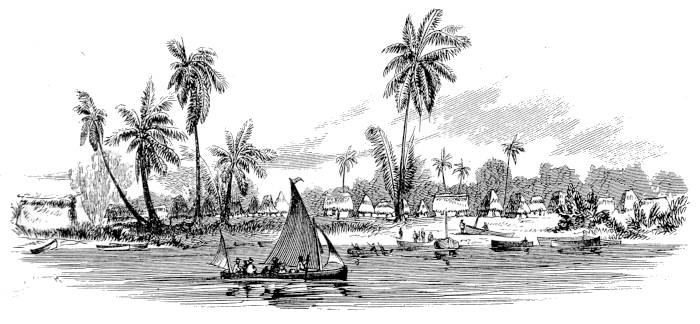

| 14—Pueblo of San Miguelito, |

99 |

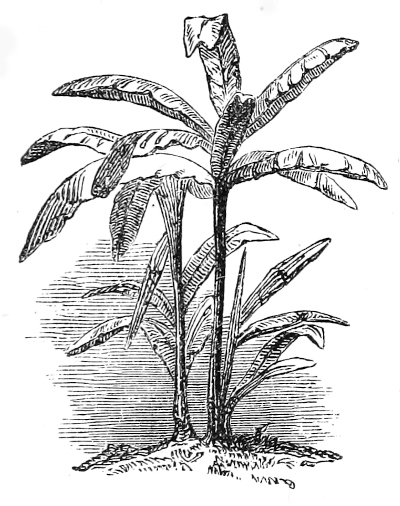

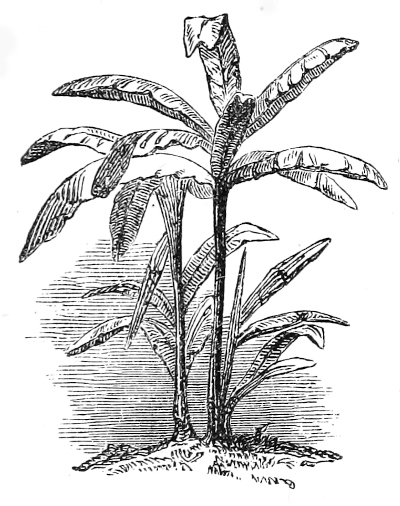

| 15—The Plantain Tree, |

119 |

| 16—Ancient Vase, |

120 |

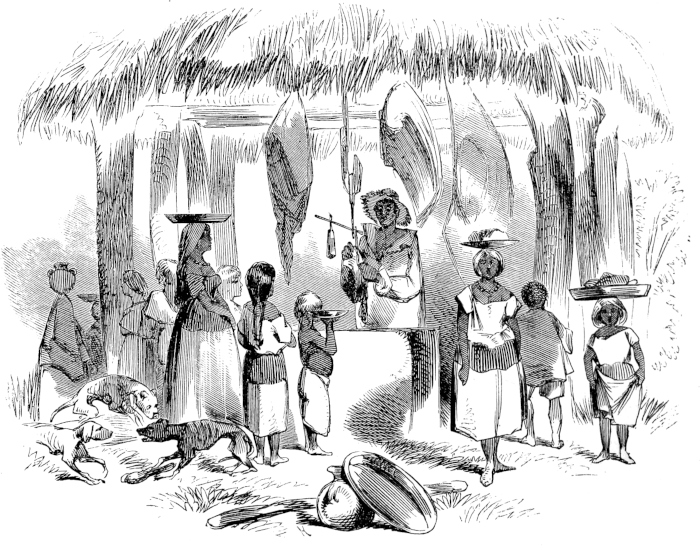

| 17—Nicaraguan Meat Market, |

120 |

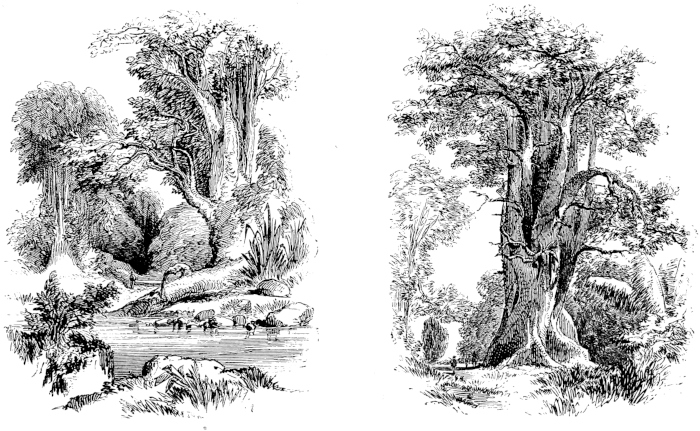

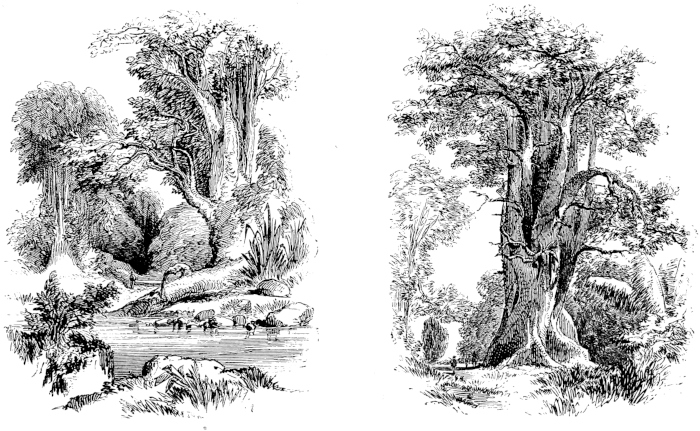

| 18—Views on Road to the Malaccas, |

156 |

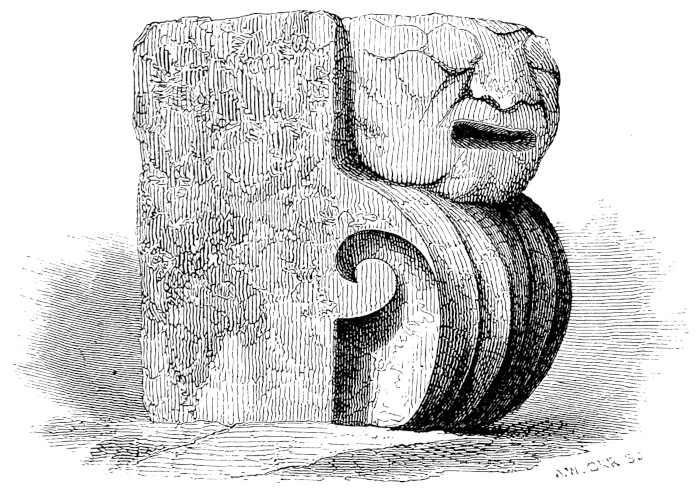

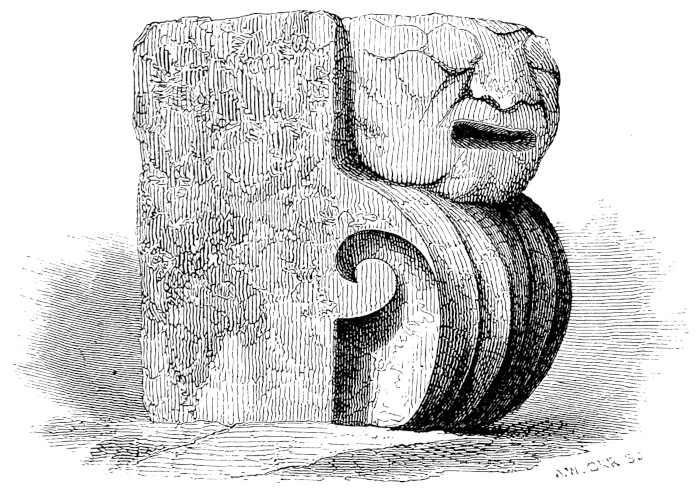

| 19—Piedra de la Boca, |

179 |

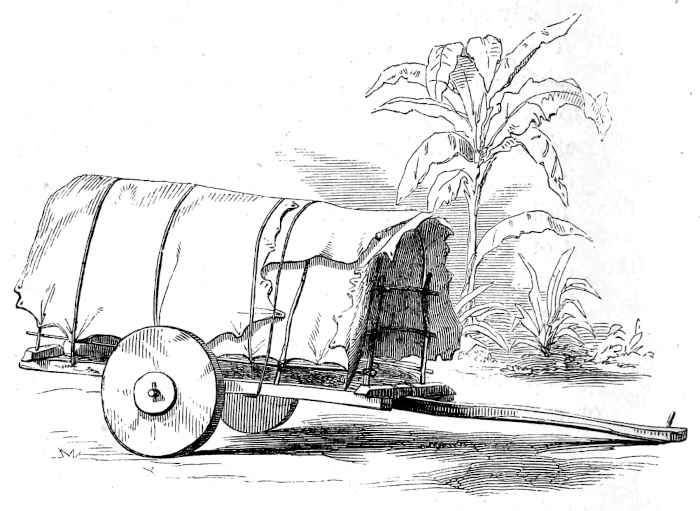

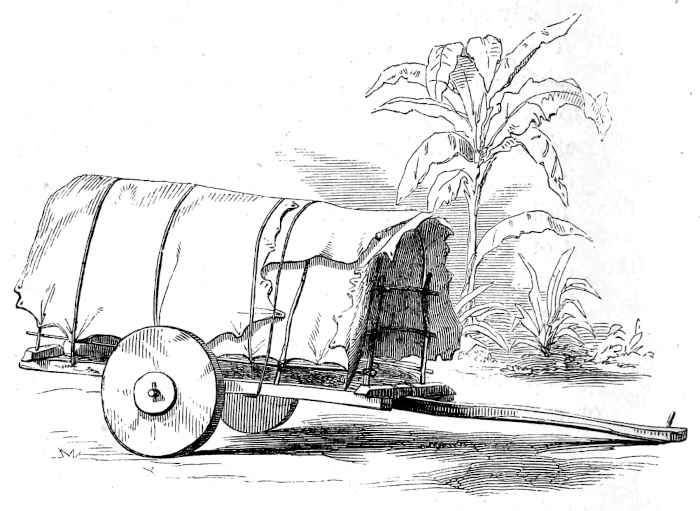

| 20—Nicaraguan Cart, |

182 |

| 21—Agricultural Implements, |

200 |

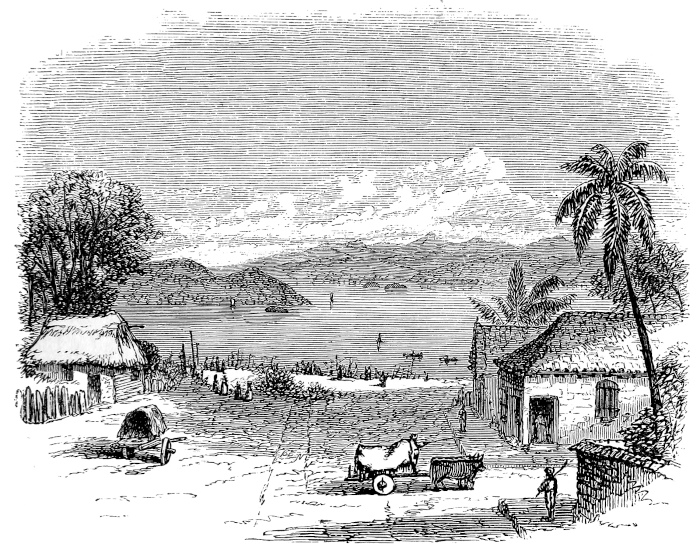

| 22—View of Lake Managua, |

209 |

| 23—View near Nagarote, |

209 |

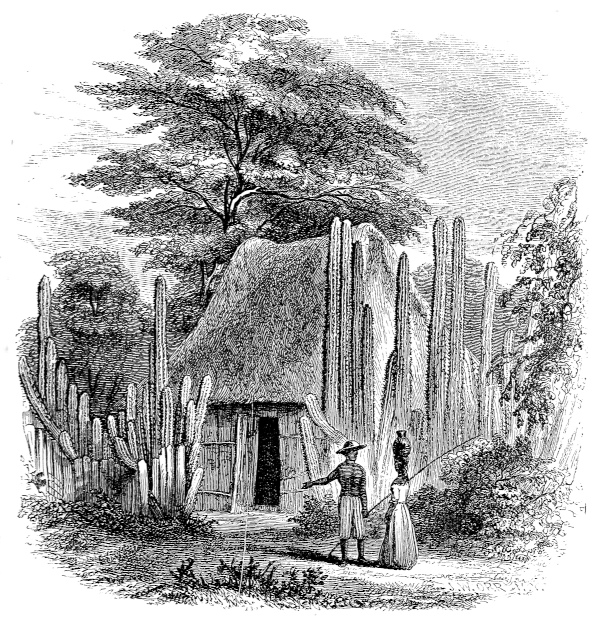

| 24—House in Pueblo Nuevo, |

221 |

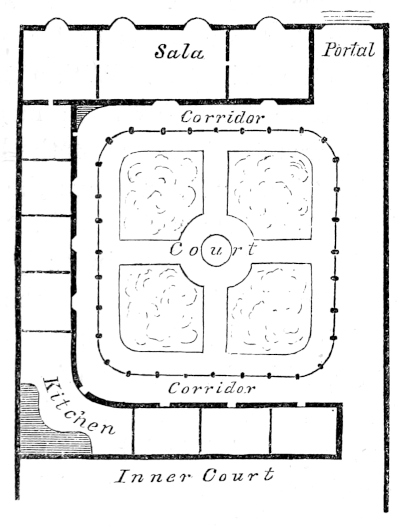

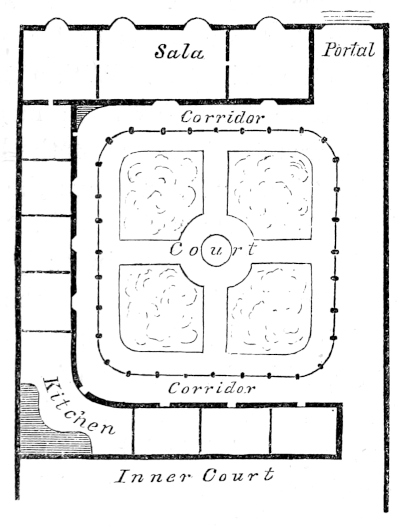

| 25—Plan of House in Leon, |

241 |

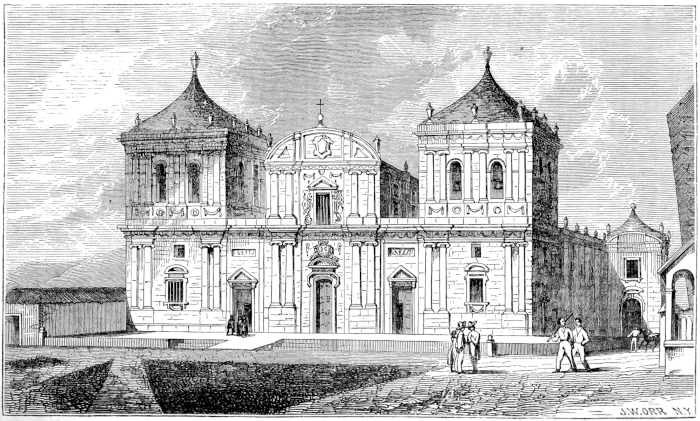

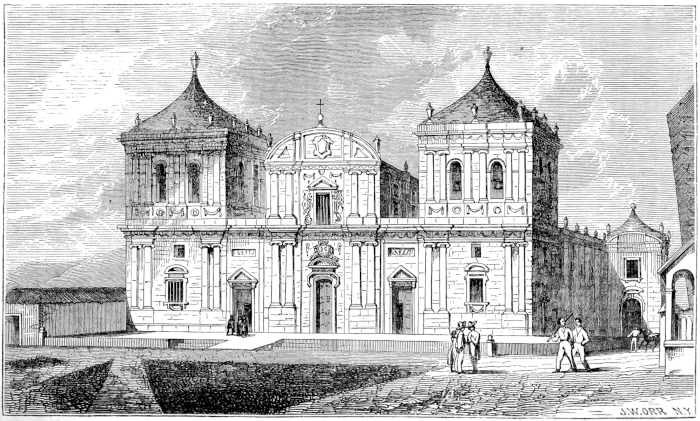

| 26—Great Cathedral of Leon, |

244 |

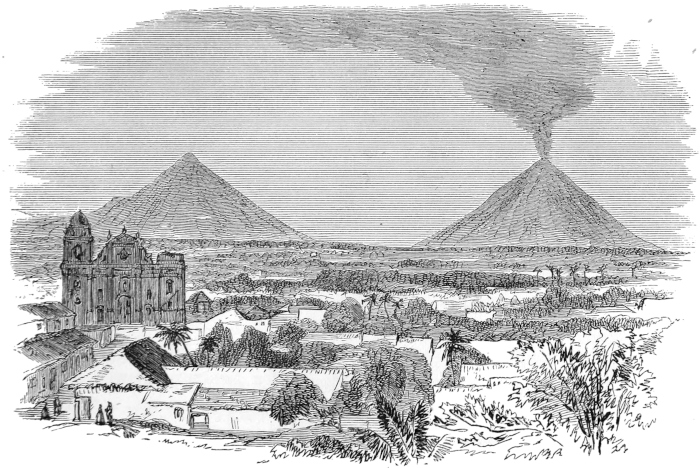

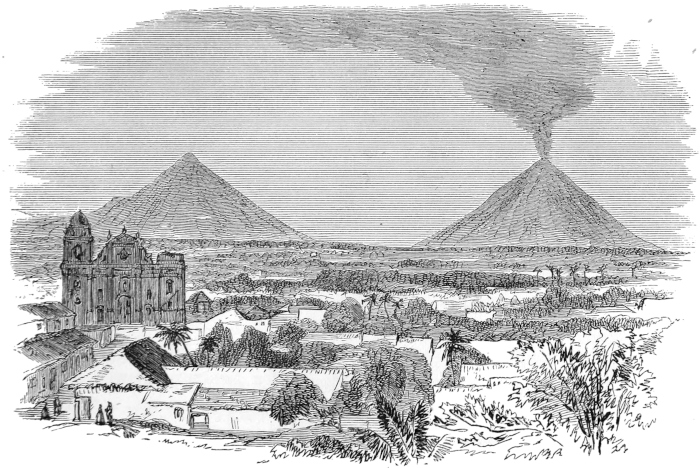

| 27—Church of Merced and Volcano of El Viejo, |

247 |

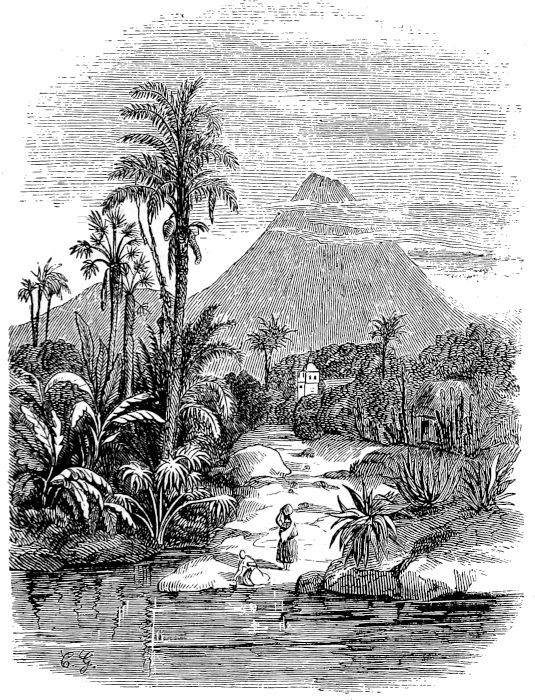

| 28—Volcanoes of Axusco and Momotombo, |

247 |

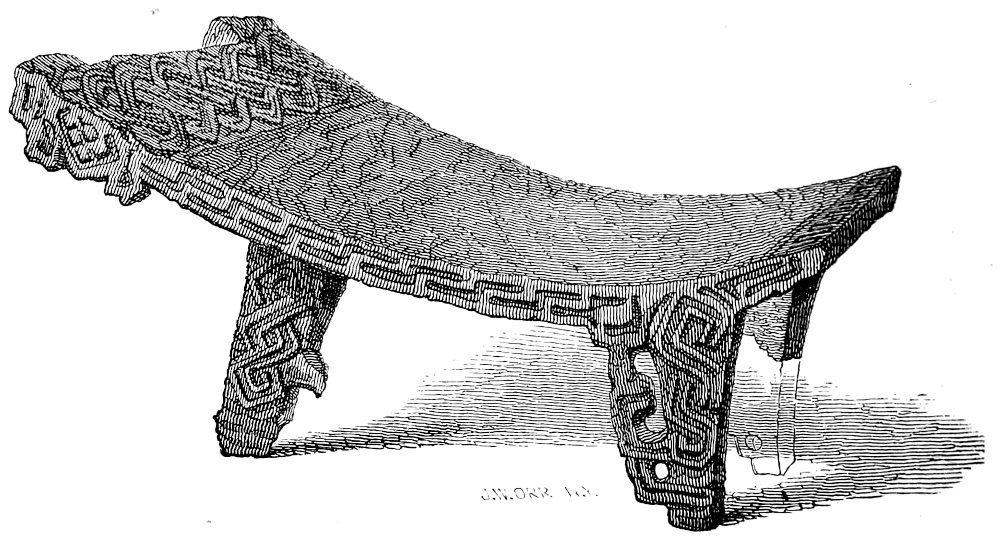

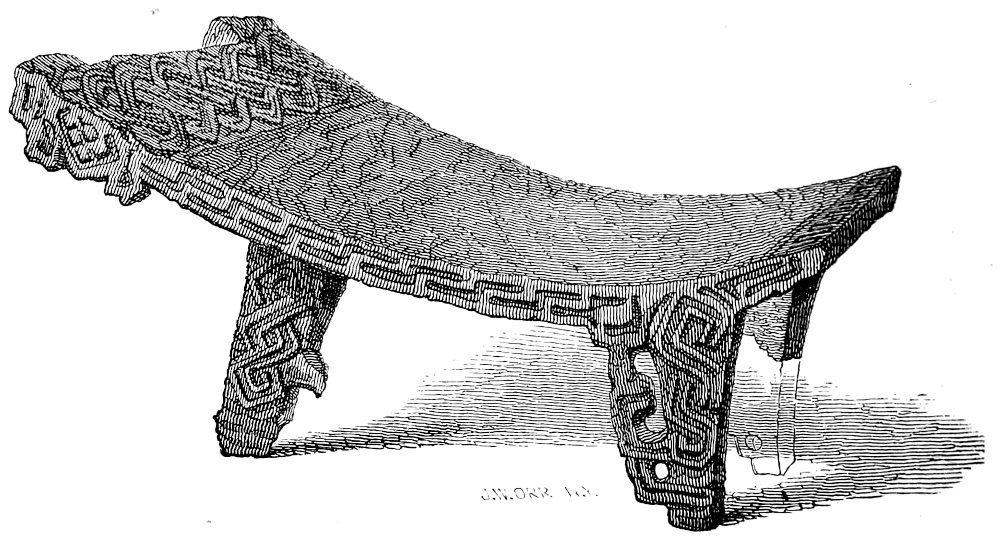

| 29—Ancient Metlal or Grinding Stone, |

256 |

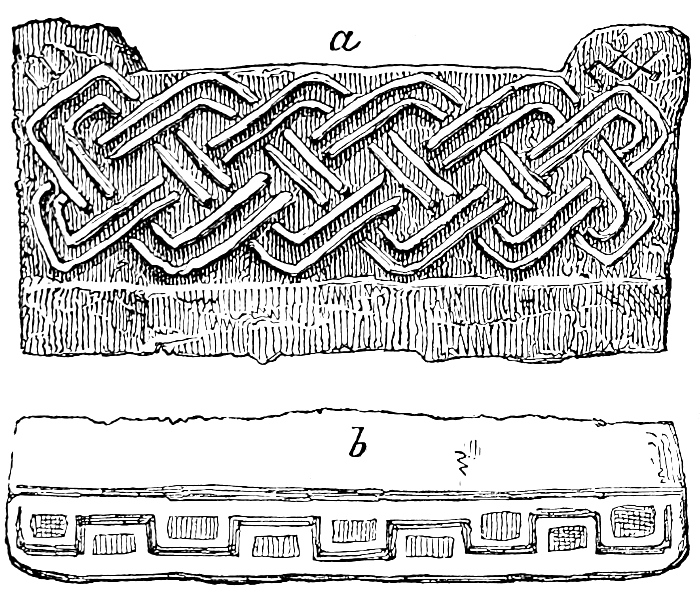

| 30—Ornaments on Same, |

257 |

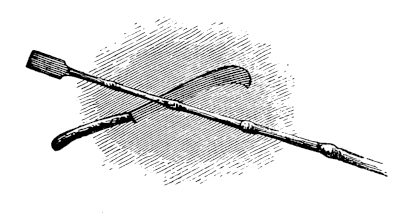

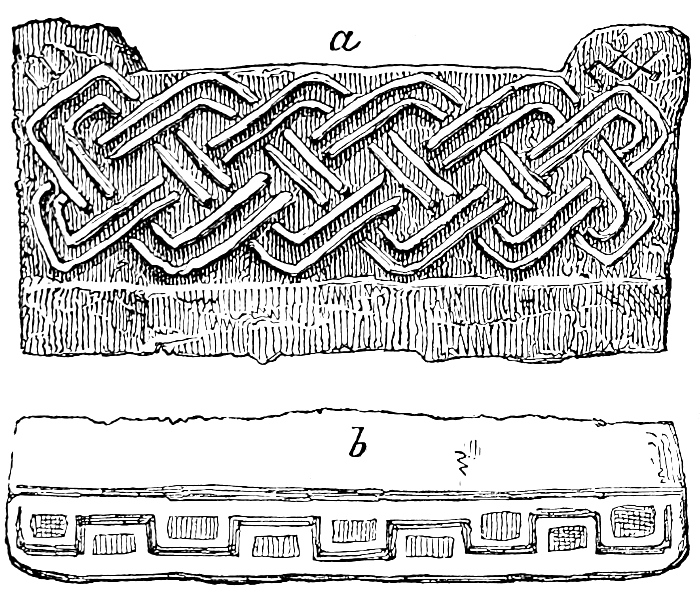

| 31—Machete and Toledo, |

260 |

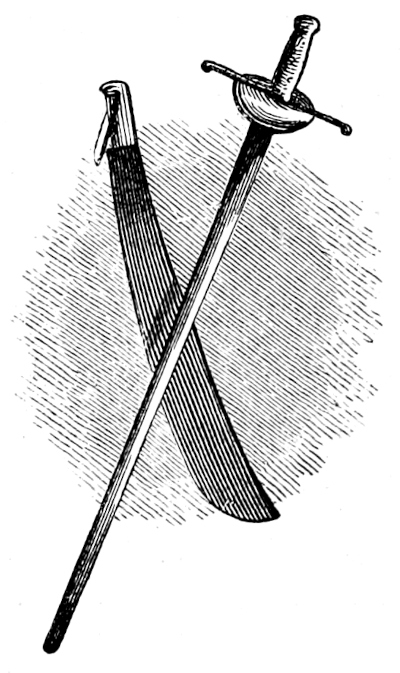

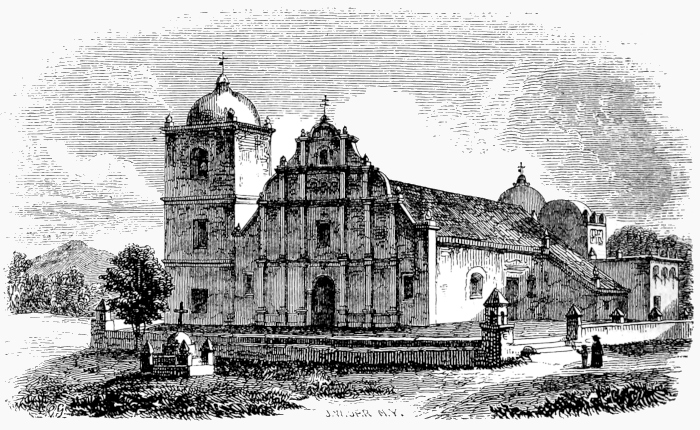

| 32—Parochial Church of Subtiaba, |

266 |

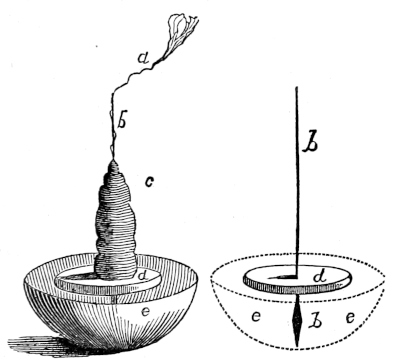

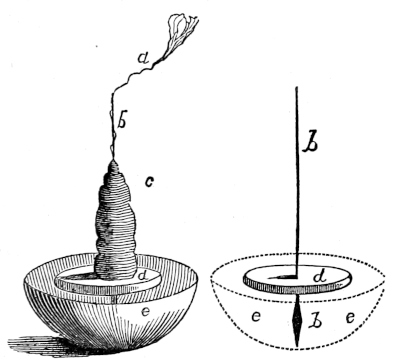

| 33—Primitive Spinning Apparatus, |

269 |

| 34—Spinning, from a Mexican MS., |

270 |

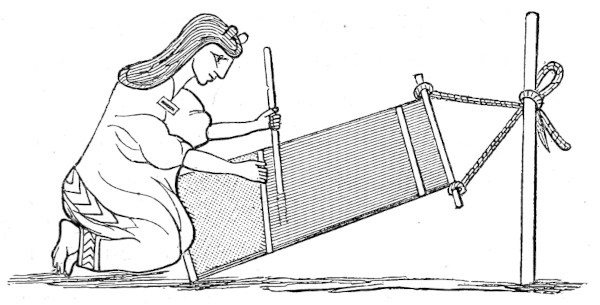

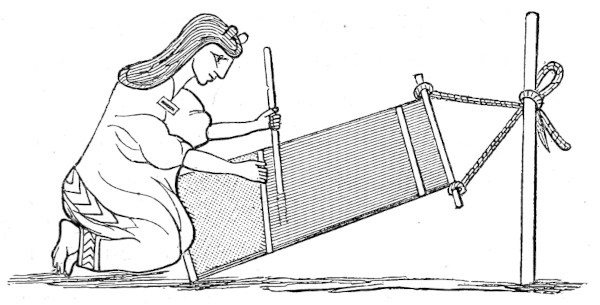

| 35—Primitive Weaving, |

271 |

| 36—Modern Pottery and Carving, |

273 |

| 37—Indian Girl, in full Costume, |

274 |

| 38—Courtyard of House in Leon, |

284 |

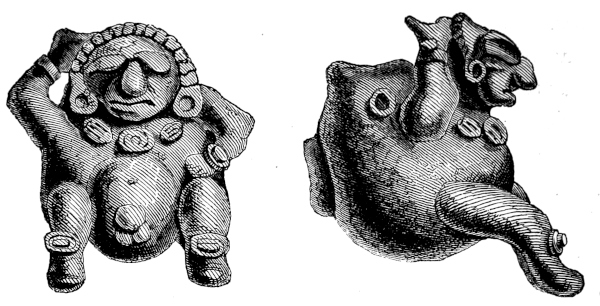

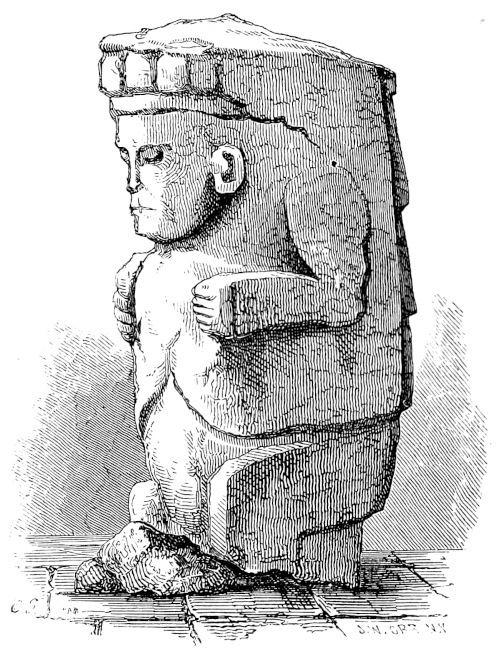

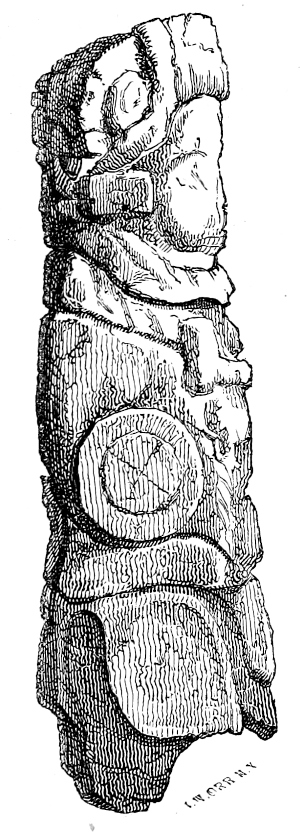

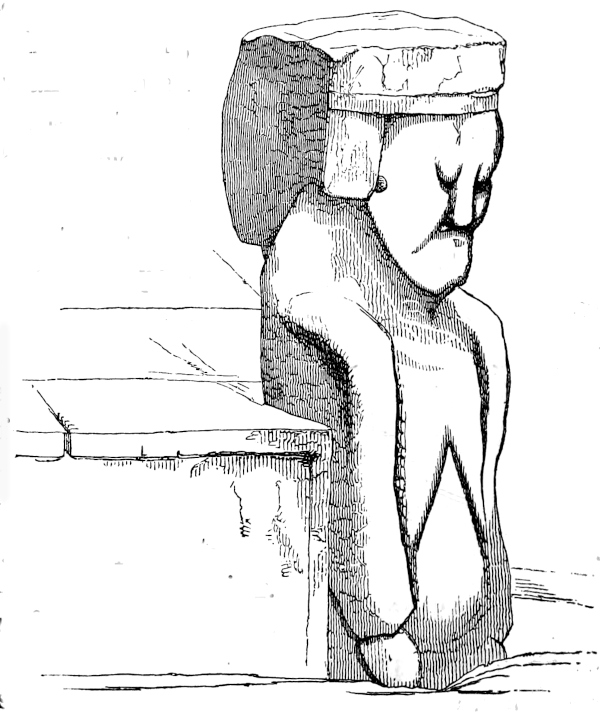

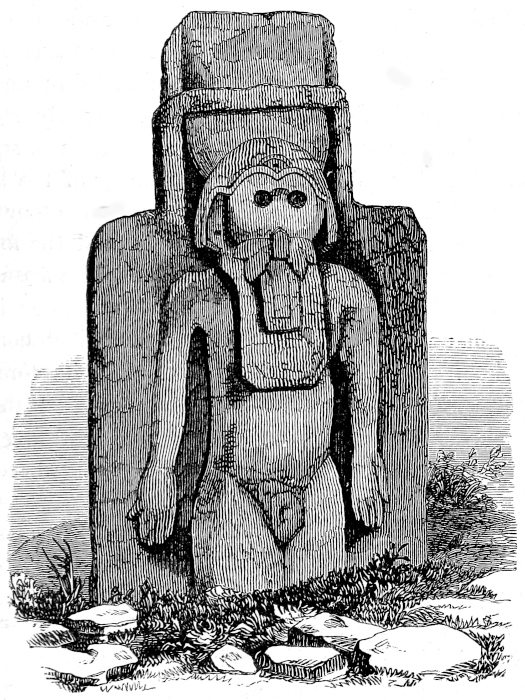

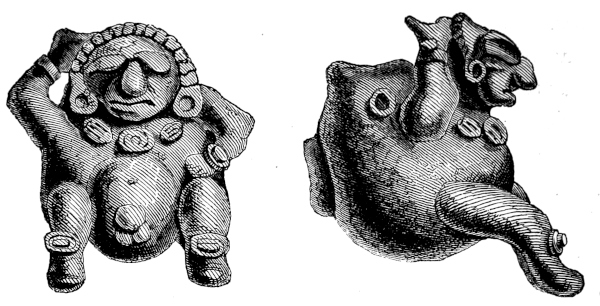

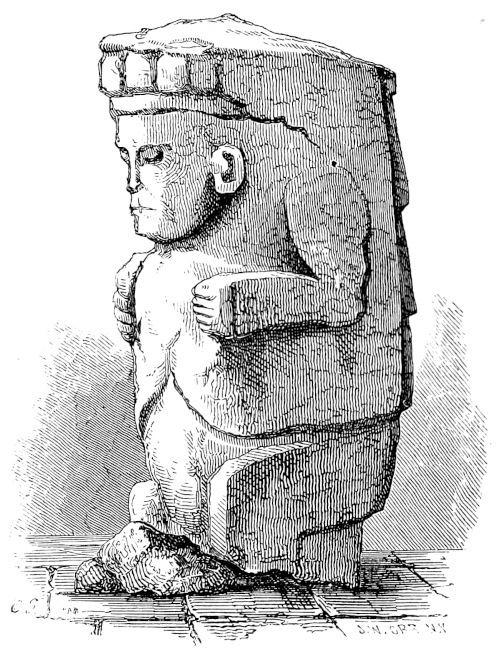

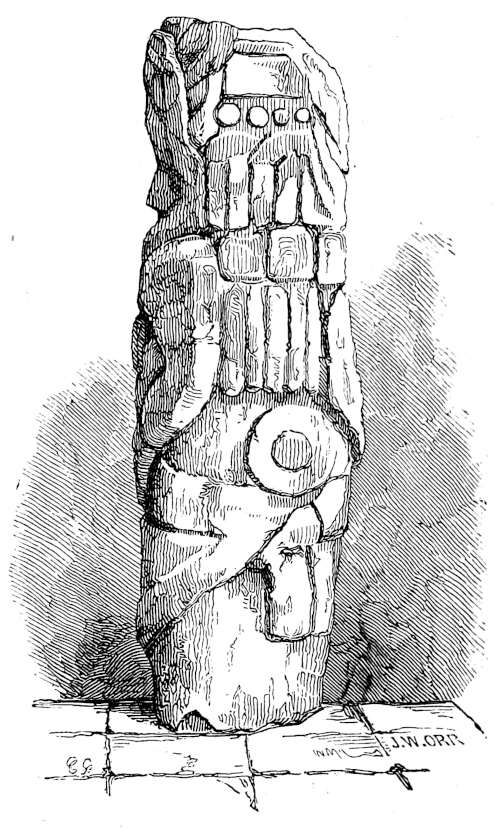

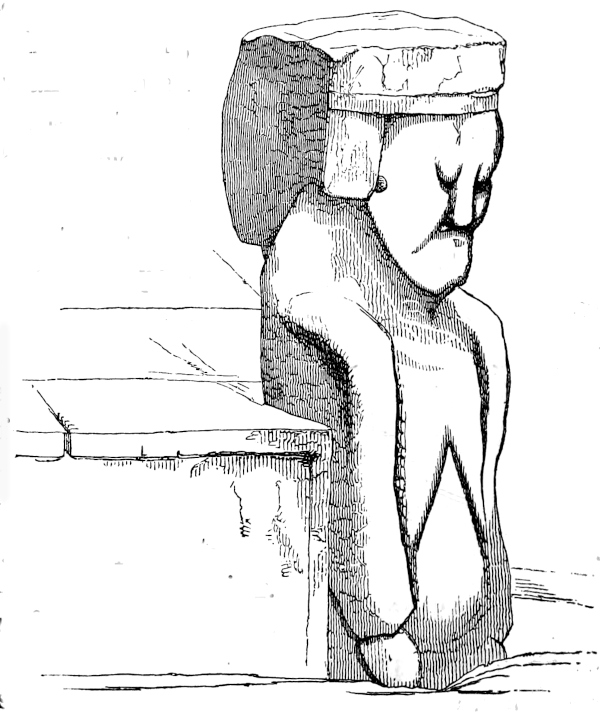

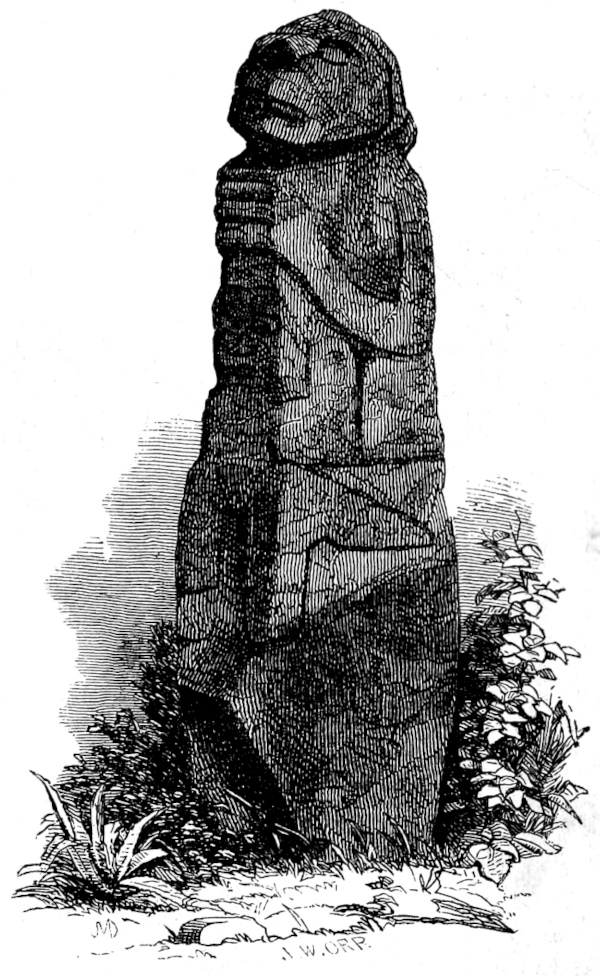

| 39—Idol from Momotombita, No. 1, |

286 |

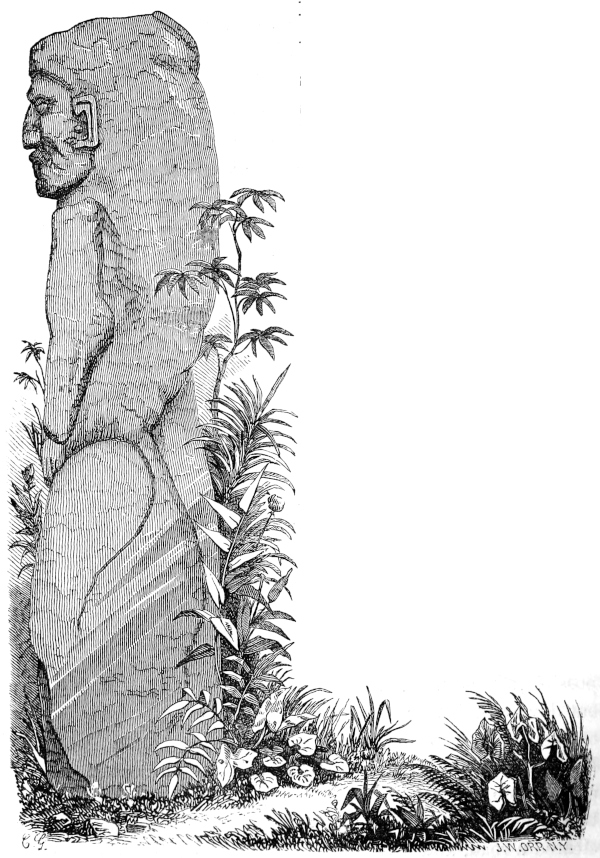

| 40—Idol from Momotombita, No. 2, |

296 |

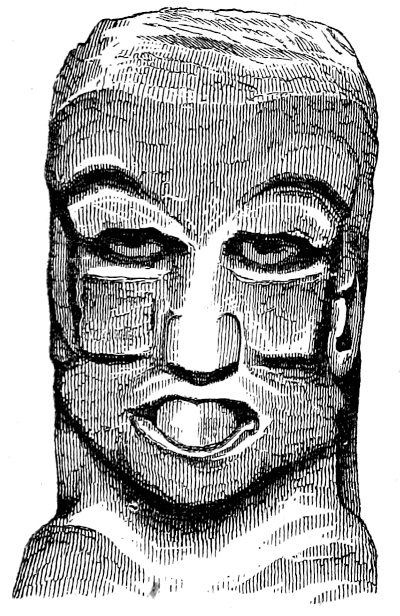

| 41—Front View of Same, |

297 |

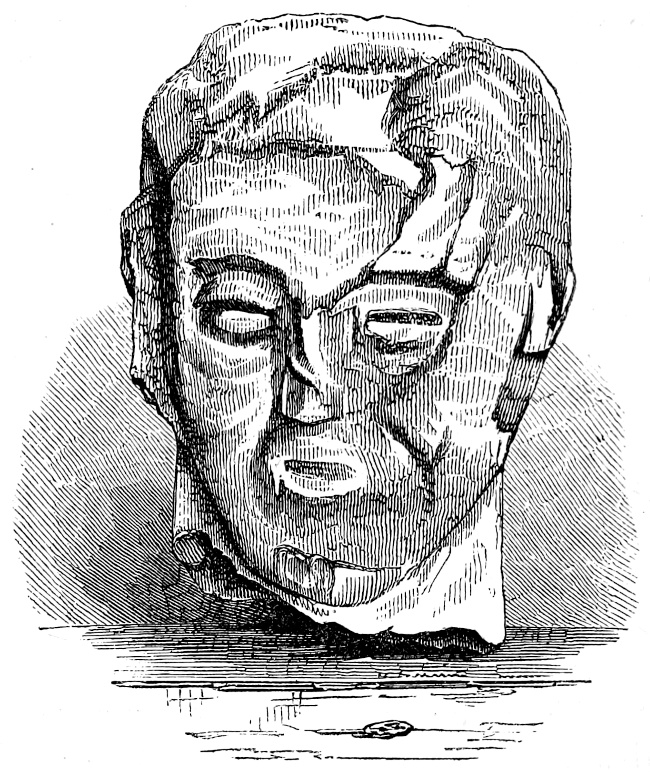

| xii42—Colossal Head from Momotombita, |

298 |

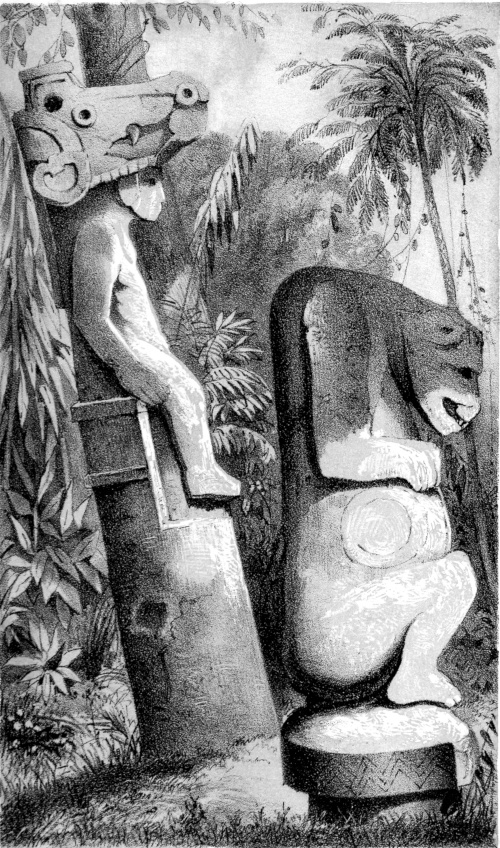

| 43—Idol from Subtiaba, No. 1, |

302 |

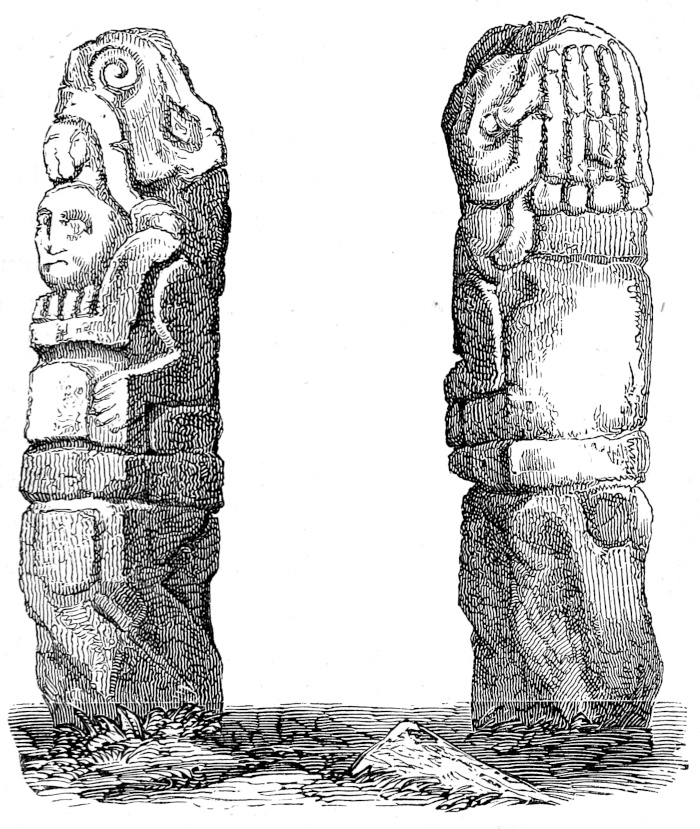

| 44—Idol from Subtiaba, No. 2, |

303 |

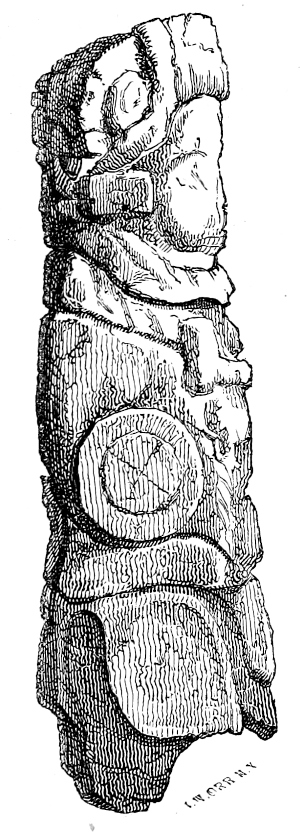

| 45—Idol from Subtiaba, No. 3, |

304 |

| 46—Side View of Idol, No. 1, |

311 |

| 47—Idol from Subtiaba, No. 4, |

312 |

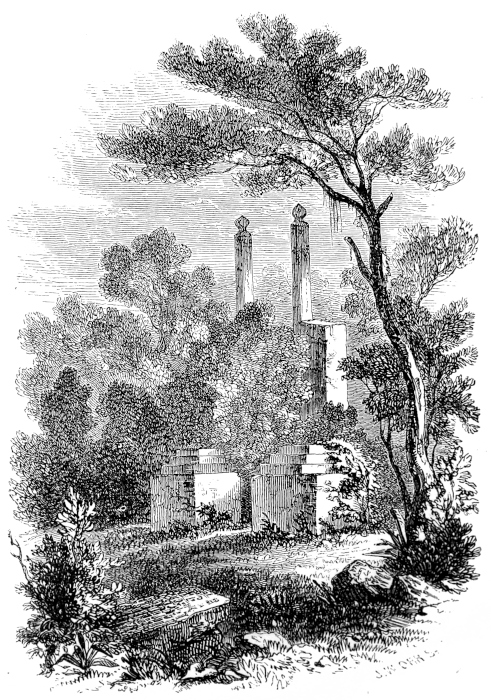

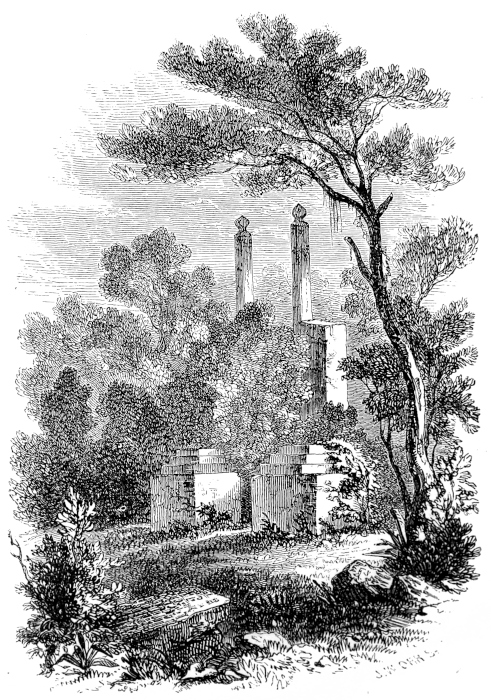

| 48—Ruins of Ancient Church, |

312 |

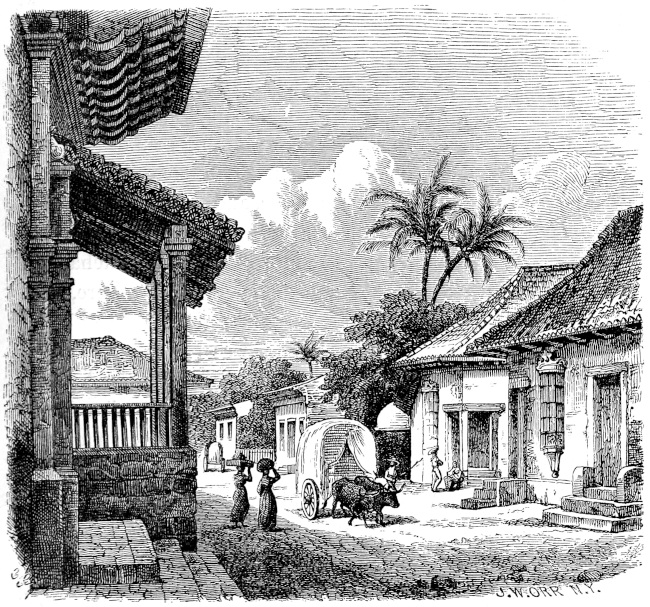

| 49—Street View in Leon, |

323 |

| 50—Nicaraguan Plough, |

327 |

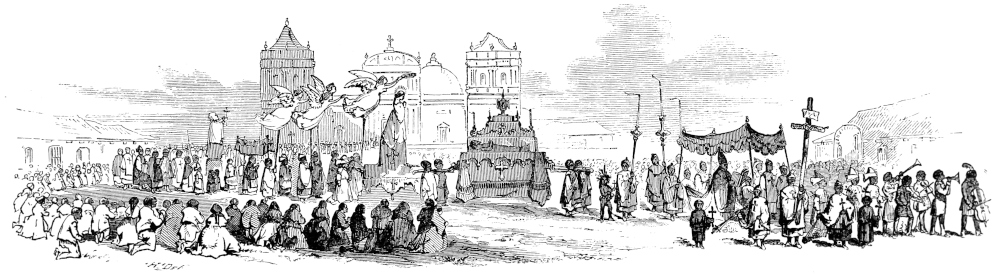

| 51—Procession of Holy Week, |

328 |

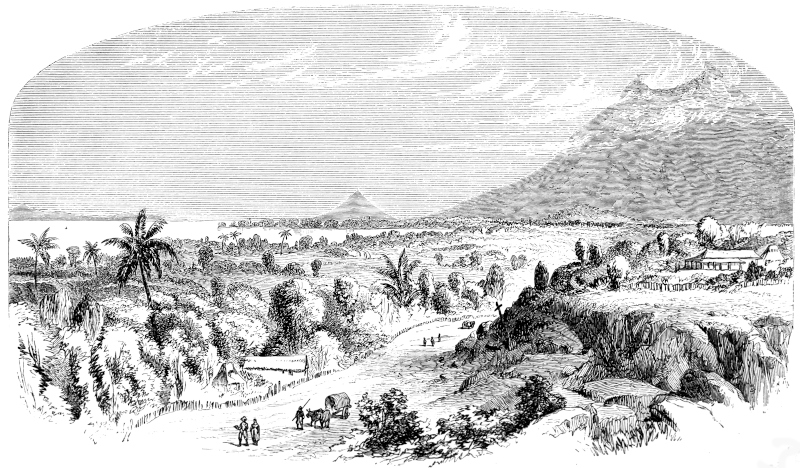

| 52—General View of Chinendaga, |

349 |

| 53—Church and Plaza of Chinendaga, |

351 |

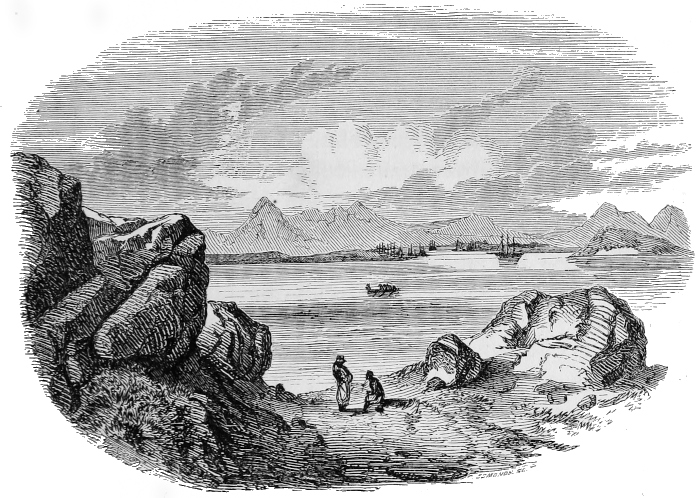

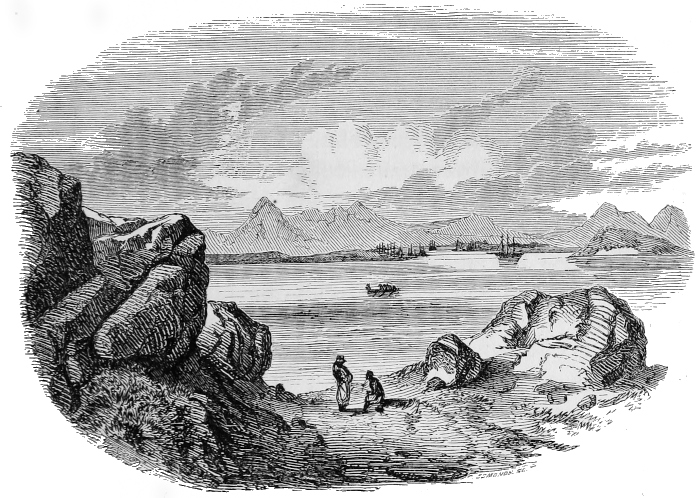

| 54—Port of Realejo, |

351 |

| 55—Lake Nihapa, an Extinct Crater, |

392 |

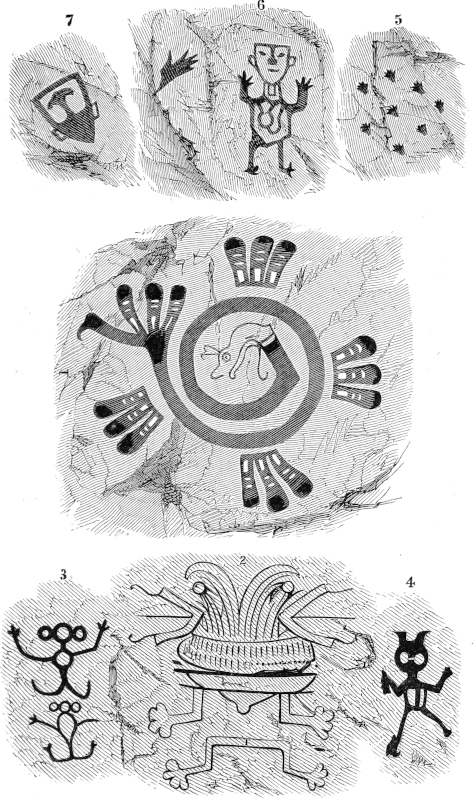

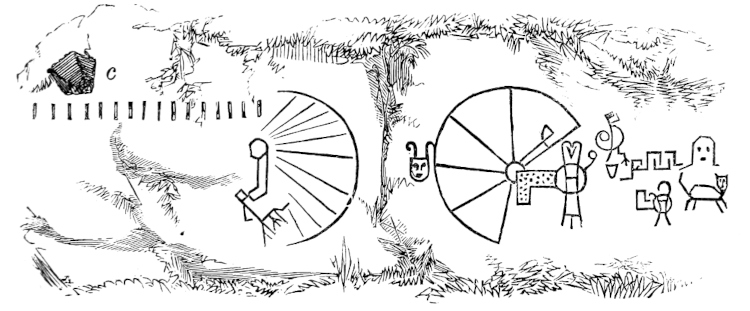

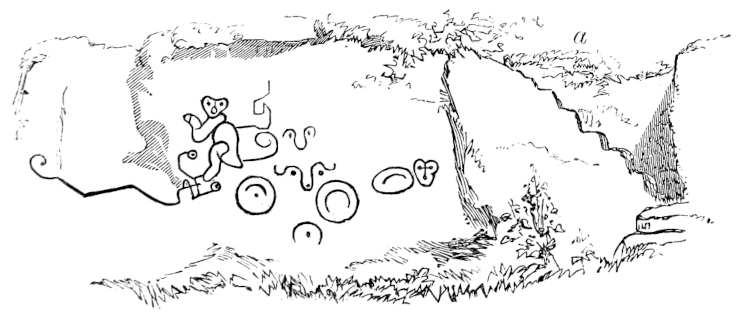

| 56—Painted Rocks of Managua, |

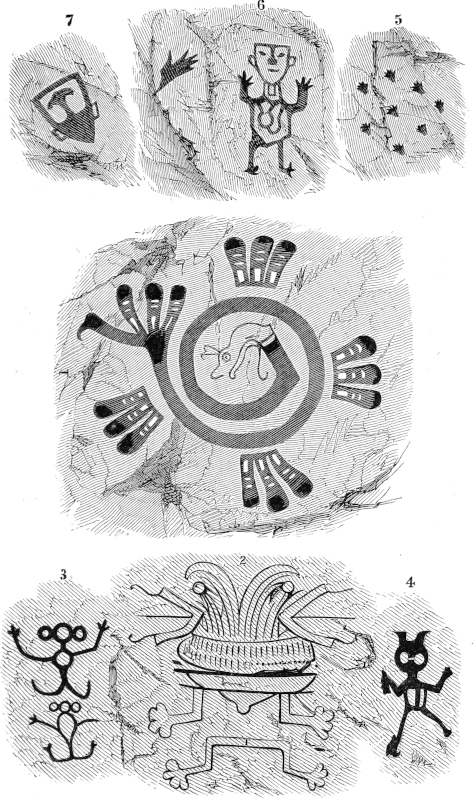

393 |

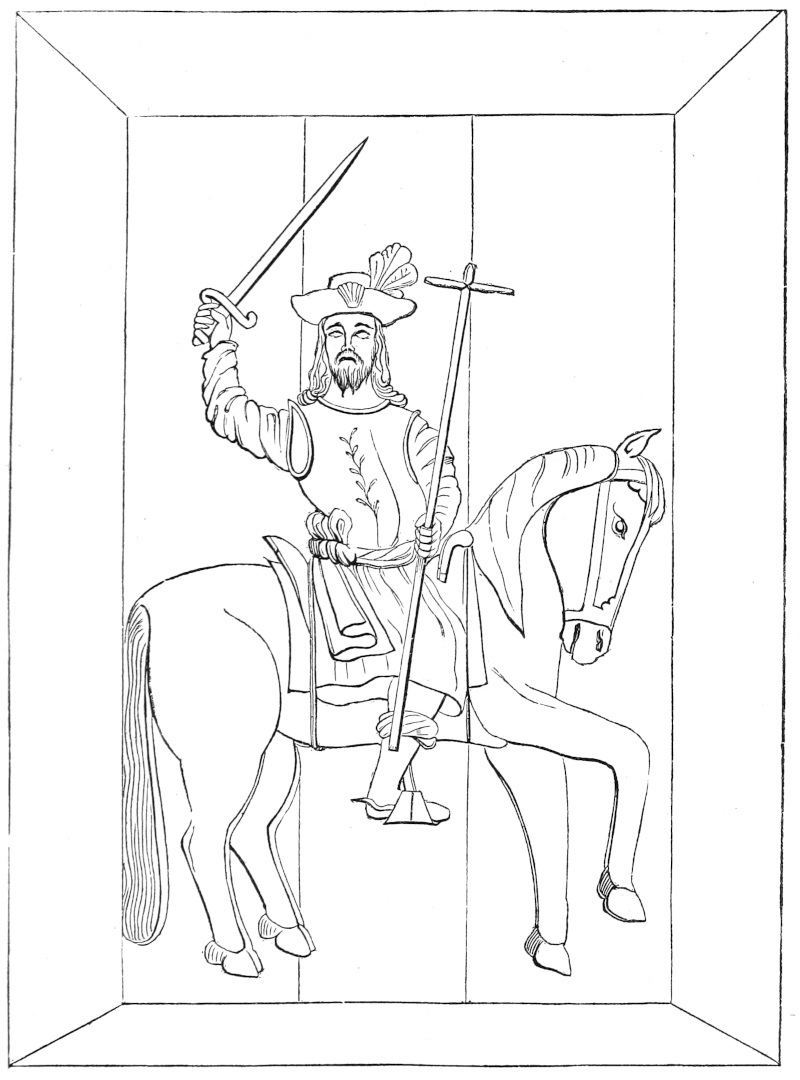

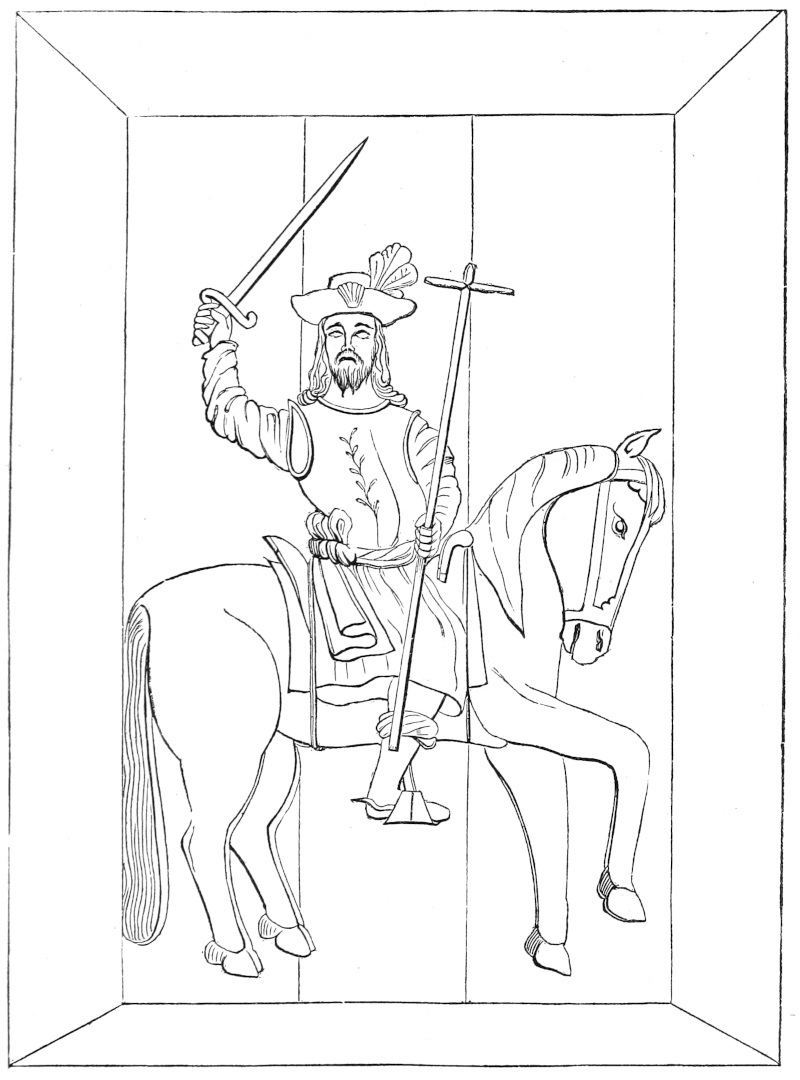

| 57—Santiago, an Ancient Carving, |

401 |

| 58—Idol at Managua, |

402 |

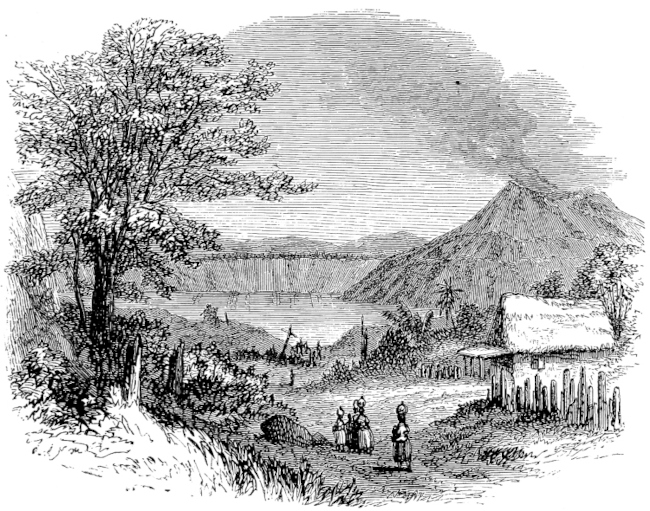

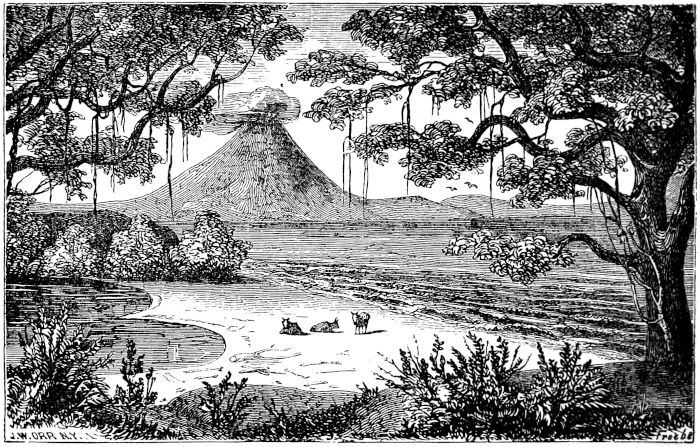

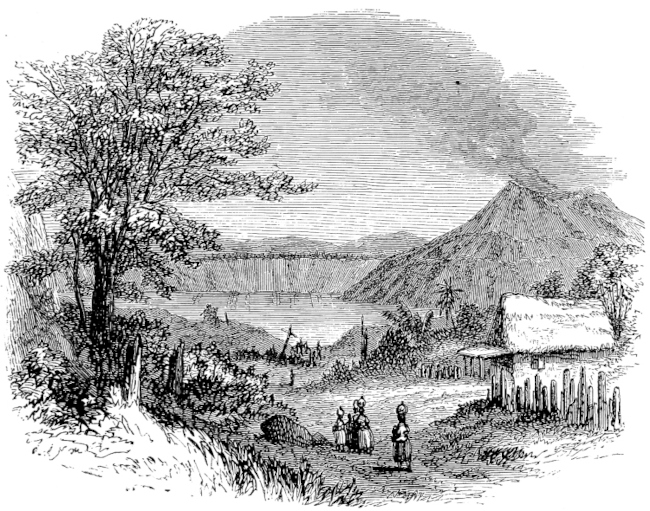

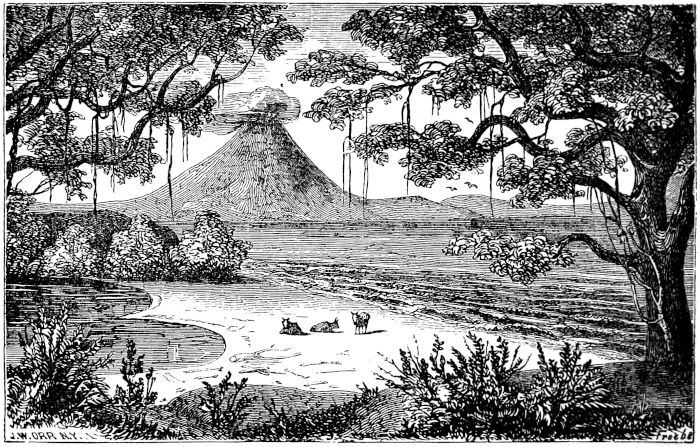

| 59—Lake and Volcano of Masaya, |

425 |

| 60—Ruined Gateway, Masaya, |

425 |

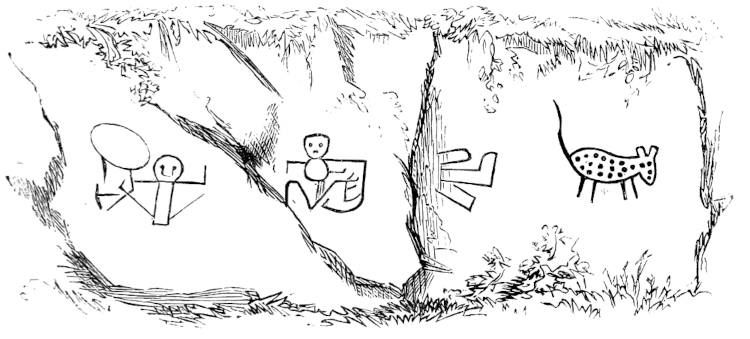

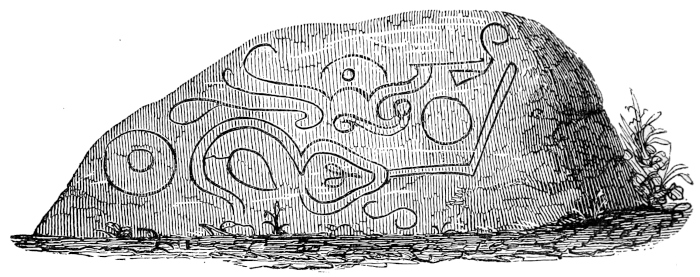

| 61—Sculptured Rocks of Masaya, |

437 |

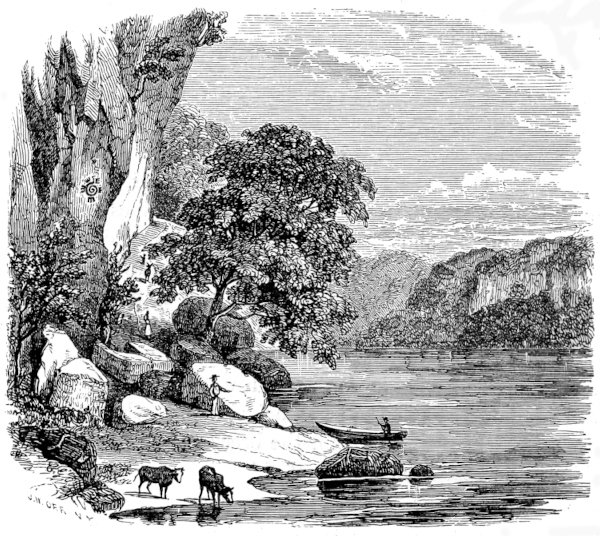

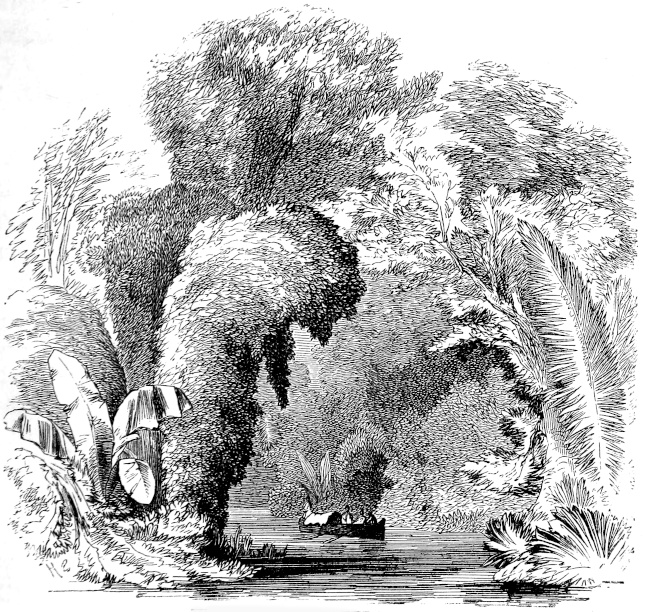

| 62—View in the “Quebrada de las Inscripciones,” |

439 |

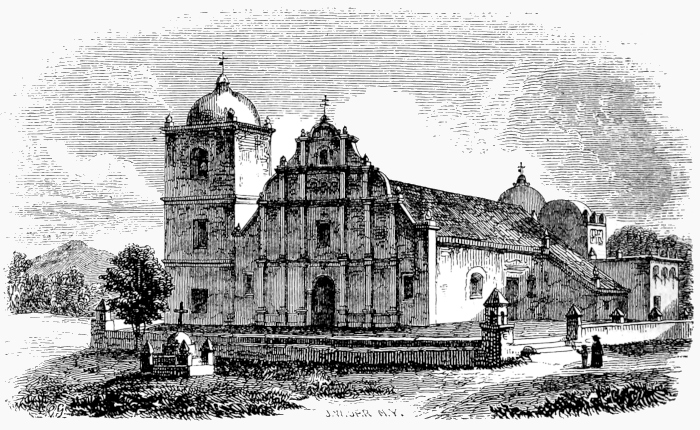

| 63—Church of San Francisco, Granada, |

443 |

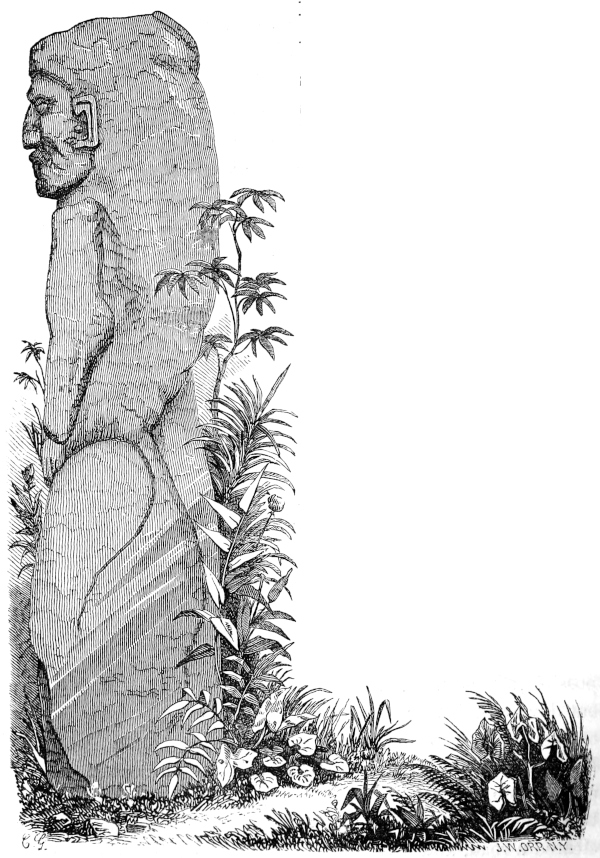

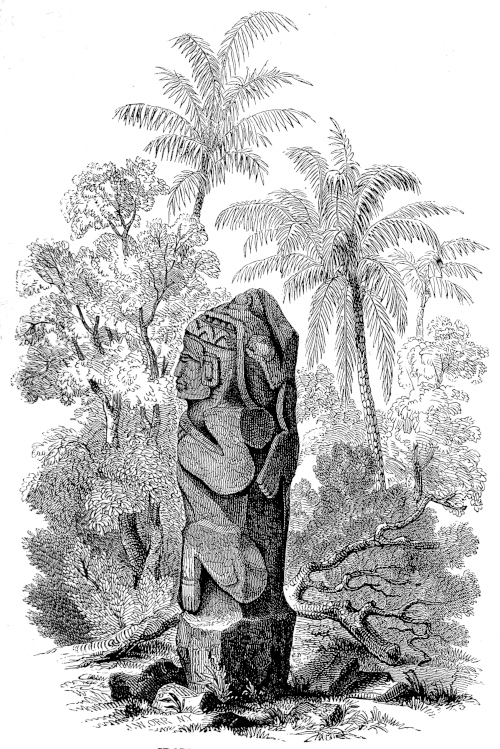

| 64—Idol at Pensacola, No. 1, |

451 |

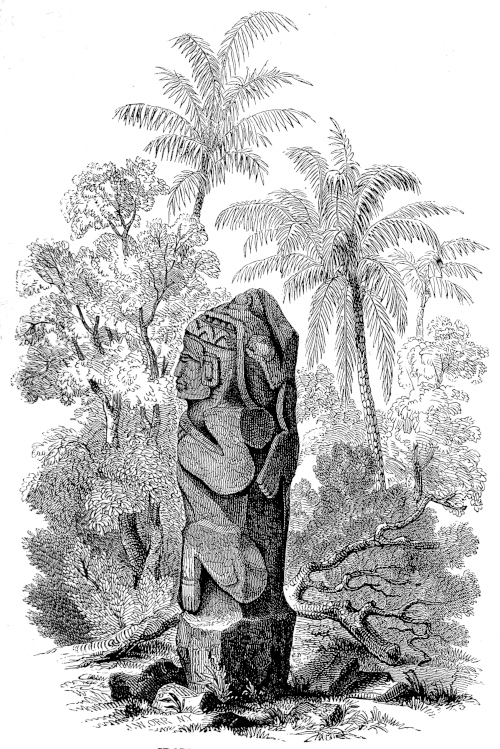

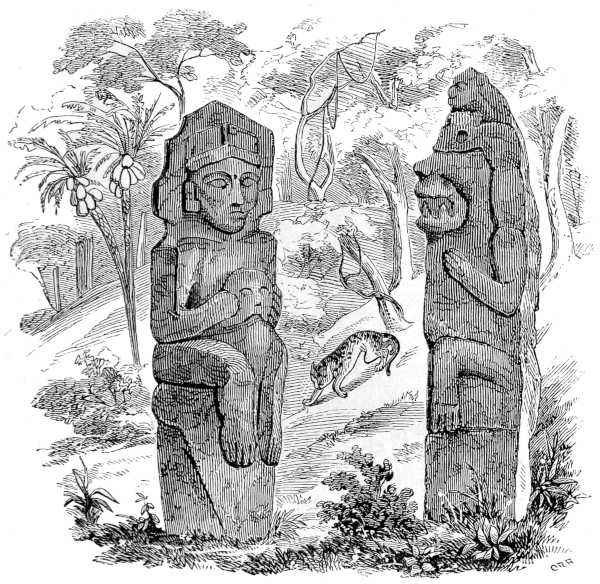

| 65—Idol at Pensacola, No. 2, |

455 |

| 66—Idol at Pensacola, No. 3, |

455 |

| 67—The Bongo “La Carlota,” |

459 |

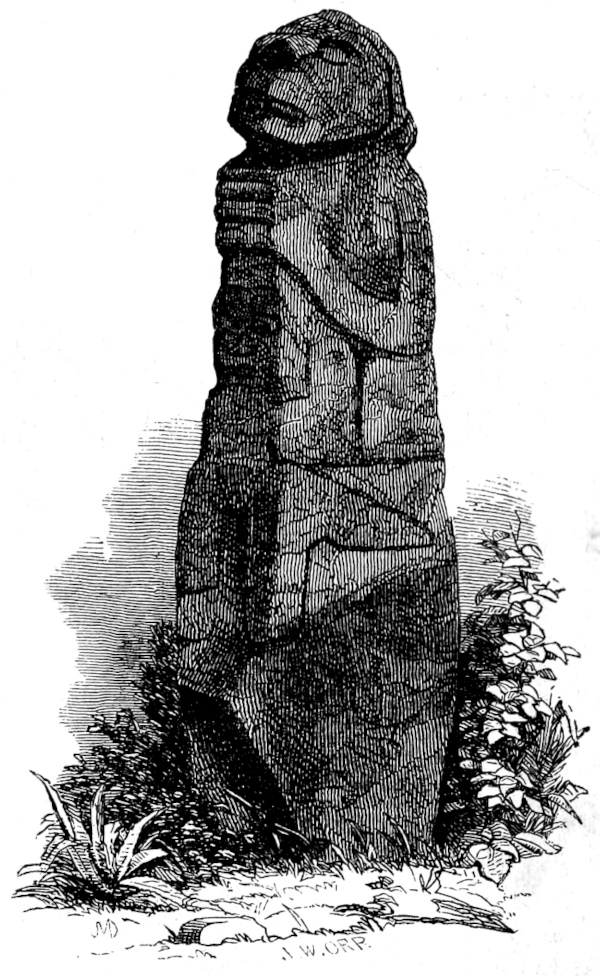

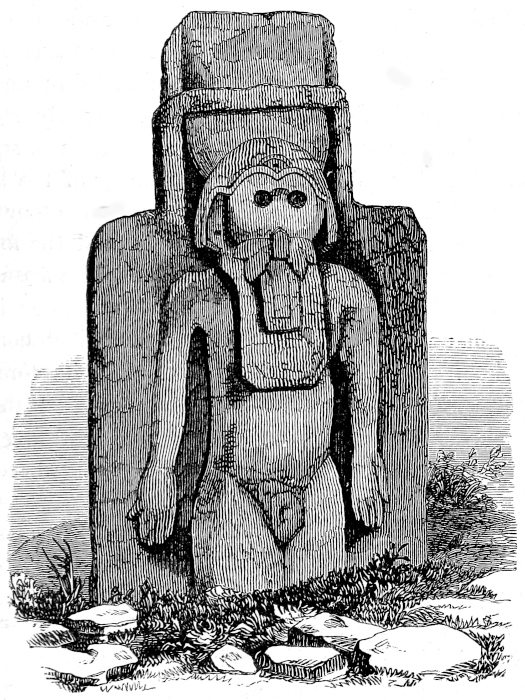

| 68—Idol at Zapatero, No. 1, |

471 |

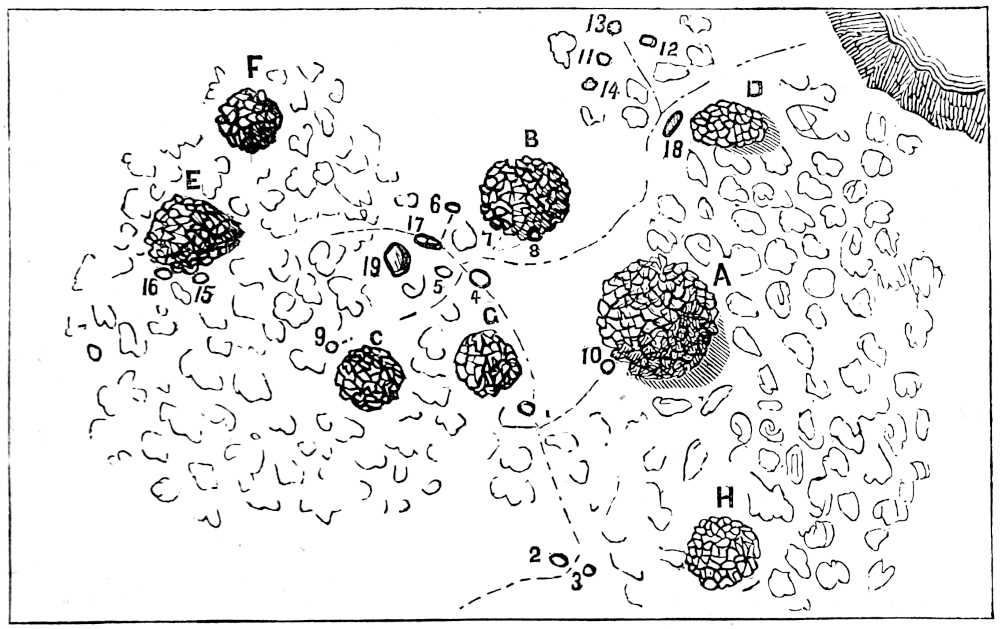

| 69—Stone of Sacrifice, |

476 |

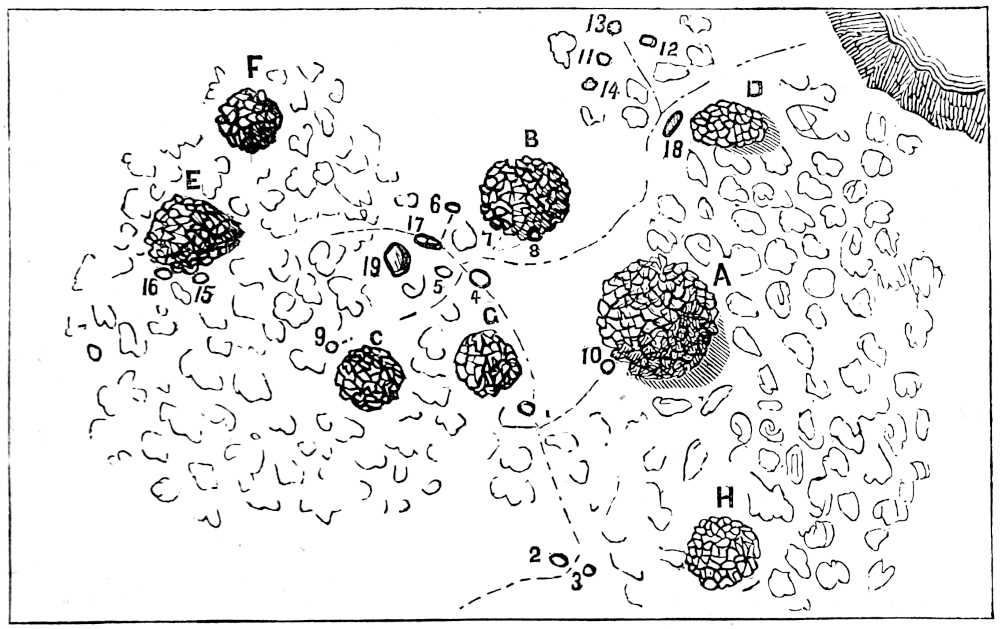

| 70—Plan of Monuments, |

477 |

| 71—Idol at Zapatero, No. 9, |

481 |

| 72—Idol at Zapatero, No. 10, |

483 |

| 73—Idols at Zapatero, Nos. 11 and 12, |

485 |

| 74—Idol at Zapatero, No. 13, |

486 |

| 75—Sculptured Rock, |

488 |

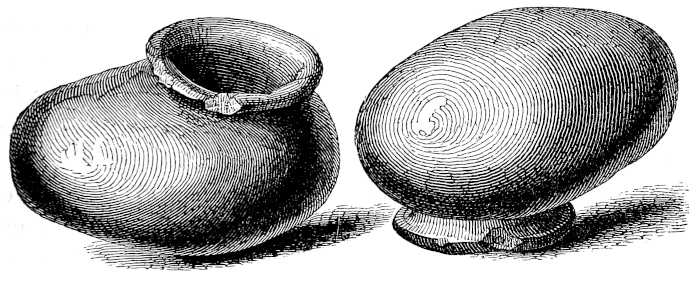

| 76—Burial Vases from Omotepec, |

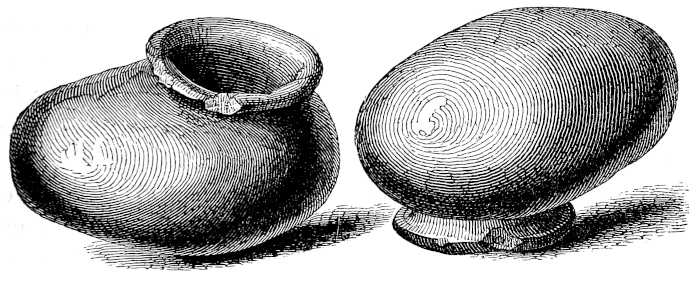

509 |

| 77—Vases from Omotepec, |

510 |

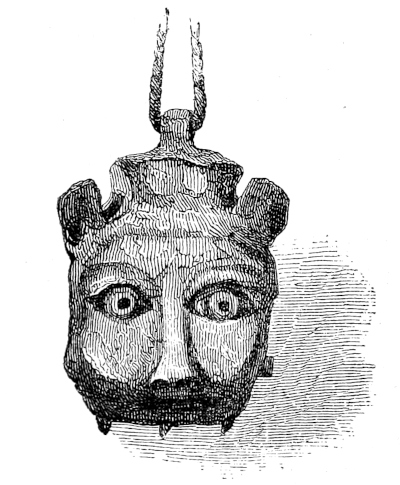

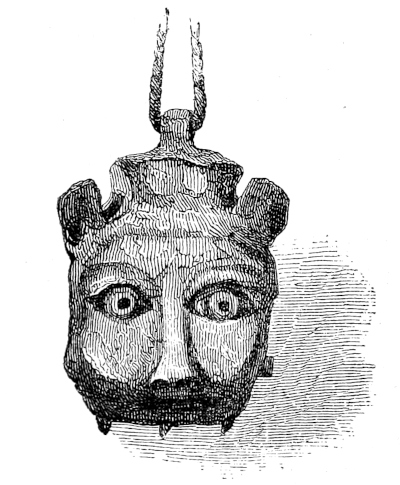

| 78—Copper Mask, |

511 |

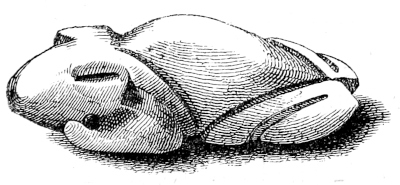

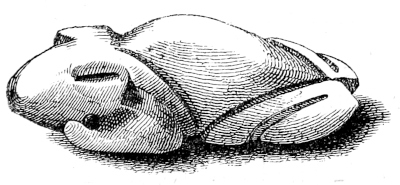

| 79—Frog in Green Stone, |

511 |

| 80—Group of Aboriginal Relics, |

515 |

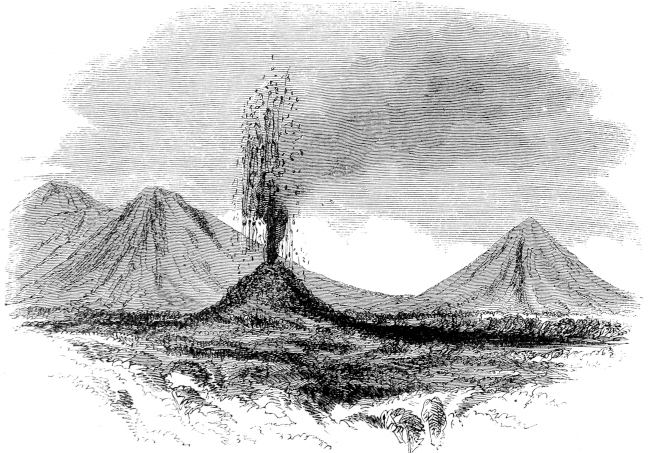

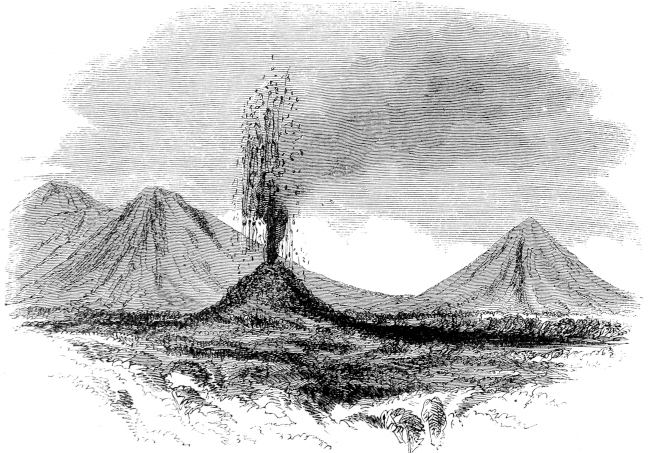

| 81—New Volcano on Plain of Leon, |

515 |

| 82—The Paroquet, |

550 |

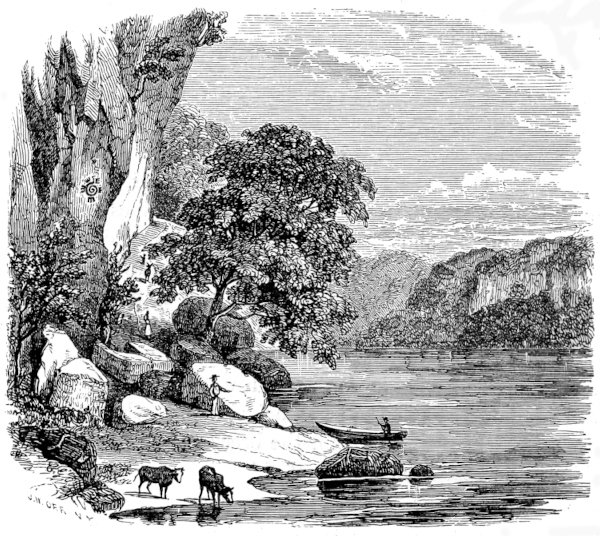

| 83—View on Lake Managua, |

560 |

| 84—The Toucan, |

574 |

| 85—The Crimson Crane, |

582 |

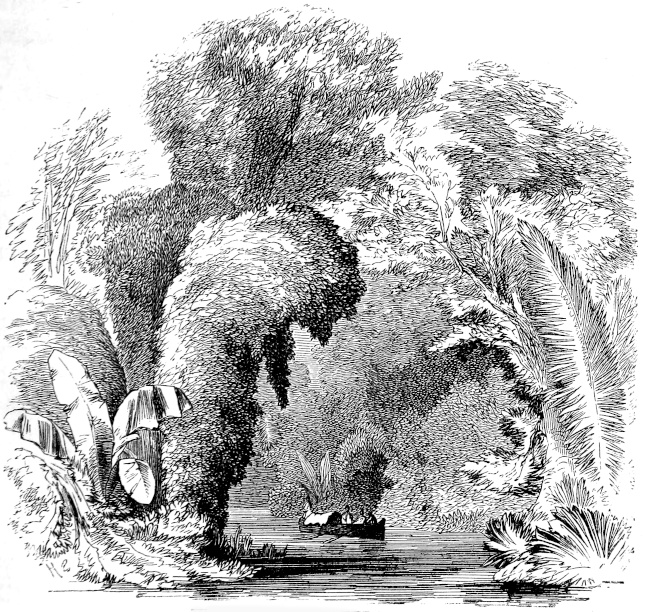

| 86—View on the Estero Real, |

587 |

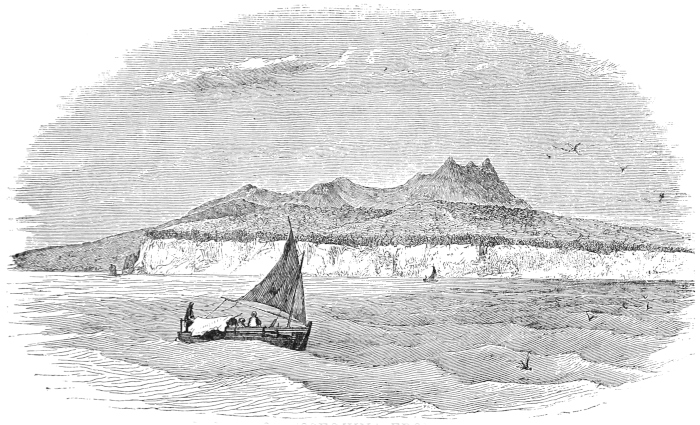

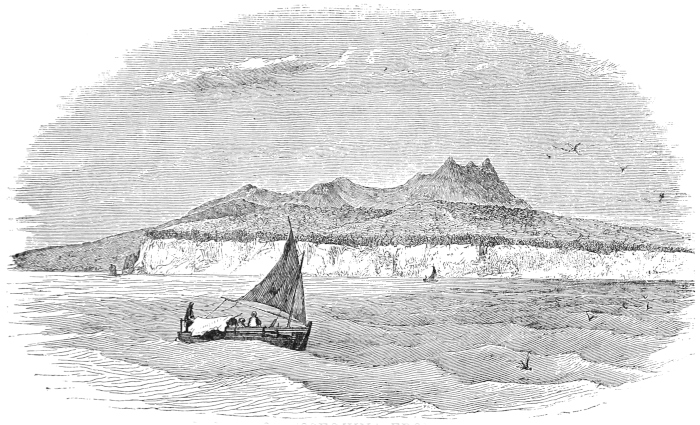

| 87—Volcano of Coseguina from the Sea, |

587 |

| 88—Volcano of Coseguina, |

589 |

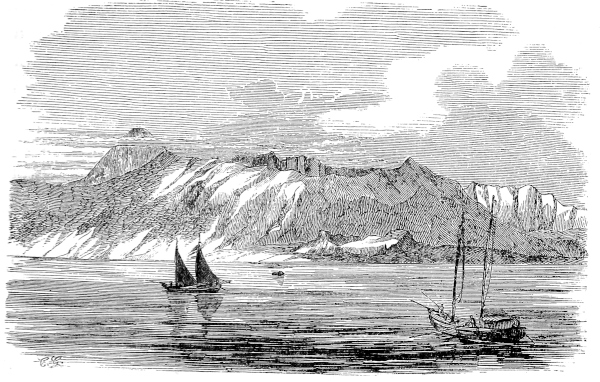

| 89—Mountain Scenery in Honduras, |

601 |

| 90—La Union and Volcano of Conchagua, |

612 |

| 91—Church of La Union, |

612 |

| 92—Las Tortilleras, |

621 |

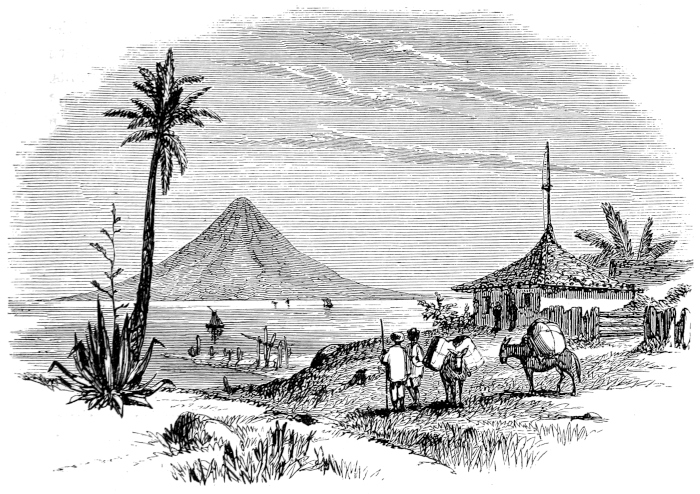

| 93—Volcano of Omotepec from Virgin Bay, |

643 |

| 94—Port of San Juan del Sur, |

646 |

| 95—Mouth of Rio Lajas, |

660 |

xiii

PREFACE

TO REVISED EDITION.

Since the publication of the original edition of this

work, in 1852, the beautiful but hapless Republic of

Nicaragua has been the theatre of a series of startling

events which have concentrated upon it not only the

attention of the American public, but of all civilized

nations. It has been made the arena of aimless, and

not always reputable diplomatic contests, and of an

obstinate and bloody struggle between a handful of

Northern adventurers and an effete and decadent race.

And unless the future shall strangely betray the indications

of the present, it is destined to pass through

a succession of still severer throes, in its advance to

that political status and commercial importance inseparable

from its geographical position and natural

resources. For, in Nicaragua, and there alone, has

xivNature combined those requisites for a water communication

between the seas, which has so long been

the dream of enthusiasts, and which is a desideratum

of this age, as it will be a necessity of the next.

There too has she lavished, with a bountiful hand,

her richest tropical treasures; and the genial earth

waits only for the touch of industry to reward the

husbandman a hundredfold with those products, which,

while they contribute to his wealth, add to the comfort

and give employment to the laborer of distant

and less favored lands.

Public interest, and especially American interest

in Nicaragua must therefore constantly increase; and

the desire to know the characteristics of the country,

its scenery and products, and the habits and

customs of its people, can never diminish. In the

Narrative which follows, these are faithfully presented;

and though, in some cases, there may be a needless

amplitude of incidents, yet even this is probably

not without its use in relieving descriptions and details

which might otherwise prove dry and repulsive

in form. In all essential respects, Nicaragua is little

changed since 1850, and since a later visit of the

author in 1854. It is true, Granada has been added

xvto its list of ruined cities, and Rivas and Masaya

bear the scars of battles on their walls. The people

have perhaps a more thoughtful look, as becomes

men realizing that the fulness of time has finally

brought them within the circle of the world’s movement,

and that they must assume and discharge the

responsibilities of their new position, or give place to

those who are equal to the requirements of this age

and prompt to recognize their duties to their fellow

men.

But in all other respects, as I have said, the country

is unchanged. Its high and regular volcanic

cones, its wooded plains, broad lakes, bright rivers,

and emerald verdure are still the same. The aguadora

still steps along firmly under her heavy water

jar, or climbs, panting, up the cliffs that surround the

Lake of Masaya. The naked children, in average

color possibly a shade lighter than before, still bestride

the hips of nurse or mother. Small and pensive

mules still trudge to market, ears and feet alone

visible beneath their green loads of sacate. The

mozo and his machete, the red-belted cavalier, on scarlet

pillion, pricking his champing horse through the

streets, the languid Señora puffing the smoke of her

xvicigaretta in lazy jets through her nostrils—the sable

priest, with gallo under his arm, hurrying to the nearest

cock pit—the shrill quien vive of the bare-footed

sentinel—the rat-tat-too of the afternoon drum—the

eternal Saints’ days, and banging bombas—all, all are

the same!

New York, September, 1859

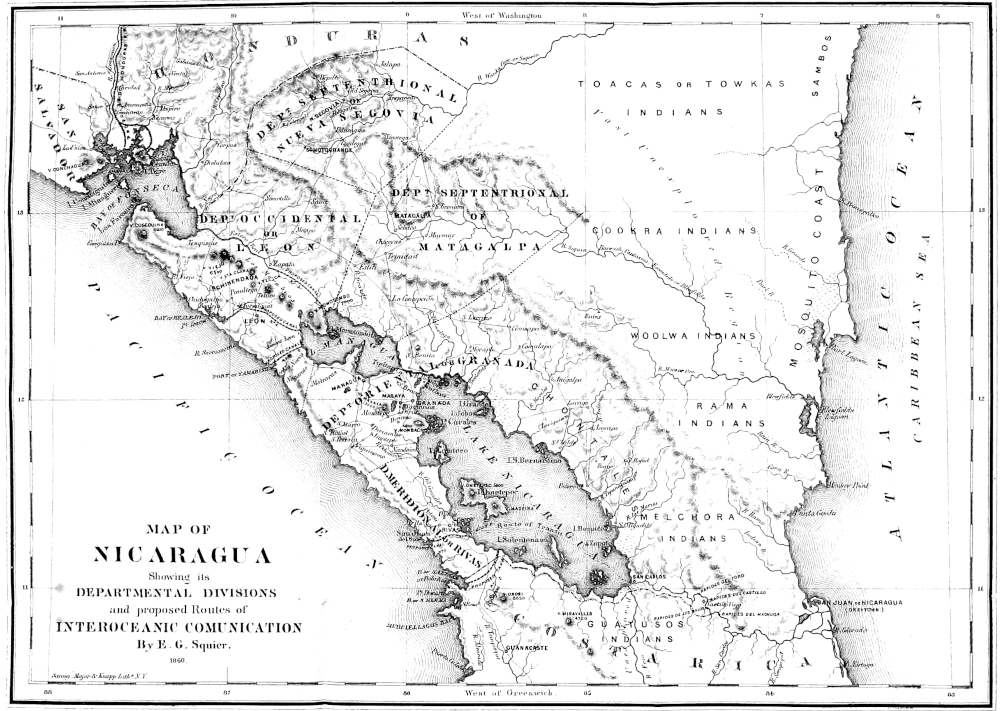

MAP OF

NICARAGUA

Showing its

DEPARTMENTAL DIVISIONS

and proposed Routes of

INTEROCEANIC COMMUNICATIONCOMMUNICATION

By E. G. Squier.

1860

CHAPTER I.

THE BRIG FRANCIS—DEPARTURE FROM NEW YORK—SAN DOMINGO—THE COAST

OF CENTRAL AMERICA—MONKEY POINT—SHREWD SPECULATIONS—A NAKED

PILOT—ALMOST A SHIPWRECK—SAN JUAN DE NICARAGUA—MUSIC OF THE

CHAIN CABLE—A POMPOUS OFFICIAL—DELIVERING A LETTER OF INTRODUCTION—TERRA

FIRMA AGAIN—“NAGUAS” AND “GUIPILS”—THE TOWN AND

ITS LAGUNA—SNAKES AND ALLIGATORS—PRACTICAL EQUALITY—CELT VS.

NEGRO—A WAN POLICEMAN—THE BRITISH CONSUL GENERAL FOR MOSQUITIA—“OUR

HOUSE” IN SAN JUAN—AN EMEUTE—PIGS AND POLICE—A VISCOMTE

ON THE STUMP—A SERENADE—MOSQUITO INDIANS—A PICTURE OF PRIMITIVE

SIMPLICITY.

The following narrative will serve to give a general, and,

on the whole, it is believed, a correct notion of the State or

Republic of Nicaragua, and of the character and peculiarities

of its inhabitants, as they would be apt to impress themselves

on the mind of a traveller without strong prejudices, with

good health and a cheerful temper, and disposed withal to

regard men and things from a sunny point of view. Matters

of a didactic kind, statistics, and information on special subjects,

such as the proposed Interoceanic Canal, are left to

find a place, as they best can, after impressions and incidents—the

round of beef, in this instance, following the sweets

and pastry.

The point in Nicaragua most accessible to the traveller

from the United States, is the now well-known port of San

Juan de Nicaragua, which our respected uncle of England,

in furtherance of some occult designs of his own, has vainly

endeavored to christen anew with the ghastly name of “Greytown.”

The little brig “Francis” was up for this port in the

18early part of May, in the year of grace 1849; and, for satisfactory

reasons, overruling all choice in the premises, berths

were engaged in her for myself and companions. She lay at

the foot of Roosevelt street, in the terra incognita beyond the

Bowery,—a pigmy amongst the larger vessels which surrounded

her. We reported ourselves on board, in compliance

with the special request of the owners, at 9 o’clock on

the morning of the 11th, just as the human tide ebbed from

the high-water mark of Fourth street and Union Square, and

subsided for the day amongst the rugged banks and dangerous

shallows of Wall and Pearl streets.

The Francis had received her freight, and her decks were

encumbered with pigs and poultry, spars and tarpaulins, to

say nothing of water casks and tar barrels, forbidding in

advance any peregrinations, by unsteady landsmen, beyond

the quarter deck. The quarter deck was so called by courtesy

only: it was elevated but a few inches above the waist,

and, deducting the room occupied by hen-coops, water-casks,

and the man at the helm, afforded but about ten square

feet of space, in which the unfortunate passengers might

“recreate” themselves. This might have sufficed for men of

moderate desires, but then it was far from being “contiguous

territory.”

In a word, we found ourselves in the midst of a confusion

which none but the experienced traveller can coolly contemplate.

Our friends, or rather the more daring of them,

scrambled over the intervening decks, or hailed us from the

rigging of the neighboring vessels. We would have invited

them on board, but there was no room to receive them; besides

the descent was perilous. All partings are much alike,

but ours were made with a prodigious affectation of good

spirits. We were to have sailed precisely at ten; but when

eleven was chimed, the number which had come “expressly

to see us off,” was sensibly diminished; and at twelve we

were left to our own contemplations.

19There was a prodigious pulling of ropes; the same boxes

were tumbled from one place to another and back again;

trunks disappeared and came to light, and it seemed as if

everybody was engaged in a grand search for nobody knew

what. At one o’clock the pilot came on board. The delay

had become painful, and now we thought the time for sailing

had arrived. But the pilot was a fat man, and sat down imperturbably

upon a water-cask. “Well, Mr. Pilot, are we

off?” He deigned no audible reply, but glanced upwards significantly

towards the streamer at the masthead. The wind

blew briskly in from the Narrows. So we seated ourselves

upon the water-casks also, and watched the men who were

painting the next ship, and almost nodded ourselves to sleep,

to the monotonous “yo-ho” of the sailors unloading an Indiaman

near by. The roar of Broadway fell subdued and distant

upon our ears; and the ferry-boats and little steamers

in the river seemed to move about in silence, going to and

fro apparently without an object, like ants around an anthill.

By-and-by a little, black bull-dog of a steamer thrust itself

valiantly through the crowd of vessels, made a rope fast to

our bows, and dragged us, with a jerk, triumphantly into the

stream, past Governor’s Island, down to the outer bay, and

then left us to take care of ourselves. That night the sun

went down cold and filmy, and the Francis tumbled roughly

about amidst the dark waves of the Atlantic. * * * A

calm under the high capes of San Domingo,—an infinitude of

thunder squalls, with the pleasant consciousness of a hundred

kegs of gunpowder stowed snugly around the foot of the

mainmast,—a “close shave” on the coral reefs below Jamaica,—for

twenty-six mortal days this was all which we

had of relief from the detestable monotony of shipboard.

Blessed be steam! * * * *

It was a dark and rainy morning, when “Land on the lee-bow,”

was sung out by the man at the helm, and in less time

20than is occupied in writing it, the occupants of the close little

cabin made their way on deck, to look for the first time upon

the coast of Central America. The dim outlines of the land

were just discernible through the murky atmosphere, and

many and profound were the conjectures hazarded as to what

precise point was then in view. The result finally arrived at

was, that we were off “Monkey Point,” about thirty miles

to the northward of our destined port. This conclusion was

soon confirmed by observing, close under the shadow of the

shore, an immense rock, rising with all the regularity of the

Pyramids to the height of three hundred feet; a landmark

too characteristic to be mistaken.

We were sweeping along with a stiff breeze, and were

comforted with the assurance that we should be in port to

breakfast, “if,” as the cautious captain observed, “the wind

held.” But the perverse wind did not hold, and in half an

hour thereafter we were rocking about with a wash-tubby

motion, the most disagreeable that can be imagined, and of

which we had had three days’ experience under the Capes of

San Domingo. The haze cleared a little, and with our

glasses we could make out a long, low line of shore, covered

with the densest verdure, with here and there the feathery

palm, which forms so picturesque a feature in all tropical

scenery, lifting itself proudly above the rest of the forest, and

the whole relieved against a background of high hills, over

which the gray mist still hung like a veil.

Some of the party could even make out the huts on the

shore; but the old man at the helm smiled incredulously,

and said there were no huts there, and that the unbroken and

untenanted forest extended far back to the great ridge of the

Cordilleras. So it was when the adventurous Spaniards

coasted here three centuries ago, and so it had remained ever

since. These observations were interrupted by a heavy

shower, acceptable for the wind it brought, which filled the

idle sails, and moved us towards our haven. And though

21the rain fell in torrents, it did not deter us from getting

soaked, in vain endeavors to harpoon the porpoises that

came tumbling in numbers around our bows.

But the shower passed, and with it our breeze, and again

the brig rocked lazily on the water, which was now filled

with branches of trees, and among the rubbish that drifted

past, a broken spear and a cocoa-nut attracted particular

attention; the one showed the proximity of a people whose

primitive weapons had not yet given place to those more

effective, of civilized ingenuity, and the other was a certain

index of the tropics. The shower passed, but it had carried

us within sight of our port. Those who had previously seen

cabins on the shore could not now perceive any evidences of

human habitation, and stoutly persisted that we had lost our

reckoning, and that we were far from our destined haven.

But a trim schooner which was just then seen moving rapidly

along under a pouring shower, in the same direction with

ourselves, silenced the pretended doubters, and became immediately

a subject of great speculation. It was finally

agreed on all hands that it must be the B——, a vessel which

left New York three days before us, the captain of which had

boasted that he would “beat us in, by at least ten days.” So

everybody was anxious that the little brig should lead him

into the harbor, and many were the objurgations upon the

wind, and desperate the attempts of the sailors to avail themselves

of every “cat’s-paw” that passed.

The excitement was great, and some of the impatient passengers

inquired for sweeps, and recommended putting out

the yawl to tow the vessel in. They even forgot, such was

the excitement, to admire the emerald shores which were now

distinct, not more than half a mile distant, and prayed that a

black-looking thunder-storm, looming gloomily in the east,

might make a diversion in our favor. And then a speck was

discerned in the direction of the port; and by-and-by the

movement of the oars could be seen, and bodies swaying to

22and fro, and in due time a pit-pan, a long, sharp-pointed canoe,

pulled by a motley set of mortals, stripped to the waist, and

displaying a great variety of skins, from light yellow to coal

black, darted under our bows, and a burly fellow in a shirt

pulled off his straw hat to the captain, and inquired in bad

English, “Want-ee ah pilot?” The mate consigned him to

the nether regions for a lubber, and inquired what had become

of his eyes, and if he couldn’t tell the Francis anywhere;

the Francis, which “had made thirty-seven voyages to this

port, and knew the way better than any black son of a gun

who ever put to sea in a bread-trough!” And then the black

fellow in a shirt and straw hat was again instructed to go

below, or if he preferred, to go and “pilot in the lubberly

schooner to windward.” The black fellow looked blacker

than before, and said something in an unintelligible jargon to

the rest, and away they darted for the schooner.

Meantime the flank of the thunder storm swept towards

us, piling up a black line of water, crested with foam, while

it approached with a noise like that of distant thunder. It

came upon us; the sails fluttered a moment and filled, the

yards creaked, the masts bent to the strain, and the little brig

dashed rapidly through the hissing water. In the darkness

we lost sight of the schooner, and the shore was no longer

visible, but we kept on our way; the Francis knew the road,

and seemed full of life, and eager to reach her old anchorage.

“Don’t she scud!” said the mate, who rubbed his hands in

very glee. “If this only holds for ten minutes more, we’re

in, like a spike!”—and, strange to say, it did hold; and when

it was past we found ourselves close to “Point Arenas,” a

long narrow spit, partly covered with water, which shuts in

the harbor, leaving only a narrow opening for the admission

of vessels. The schooner was behind us, but here was a

difficulty. The bar had changed since his last trip; the captain

was uncertain as to the entrance, and the surf broke

heavily under our lee. Excitement of another character prevailed

23as we moved slowly on, where a great swell proclaimed

the existence of shallows. The captain stood in the bow,

and we watched the captain. Suddenly he cried, “Hard

a-port!” with startling emphasis, and “Hard a-port!” was

echoed by the helmsman, as he swept round the tiller. But

it was too late; the little vessel struck heavily as the wave

fell.

“Thirty-seventh, and last!” muttered the mate between

his teeth, as he rushed to the fastenings, and the main-sail

came down on the run. “Round with the boom, my men!”

and the boom swung round, just as the brig struck again,

with greater force than before, unshipping the rudder, and

throwing the helmsman across the deck. “Round again, my

men! lively, or the Francis is lost!” cheered the mate, who

seemed invested with superhuman strength and agility; and

as the boom swung round the wave fell, but the Francis did

not strike. “Clear she is!” shouted the mate, who leaped

upon the companion-way, and waved his hat in triumph;

and turning towards the schooner, “Do that, ye divil, and

call yerself a sailor!” There was no doubt about it; the

Francis was in before the schooner; and notwithstanding

the accident to her rudder, she passed readily to her old anchoring

ground, in the midst of a spacious harbor, smooth as

a mill-pond. There was music in the rattling cable as the

anchor was run out, and the Francis moved slowly round,

with her broadside towards the town. The well was tried,

but she had made no water, which was the occasion for a new

ebullition of joy on the part of the mate.

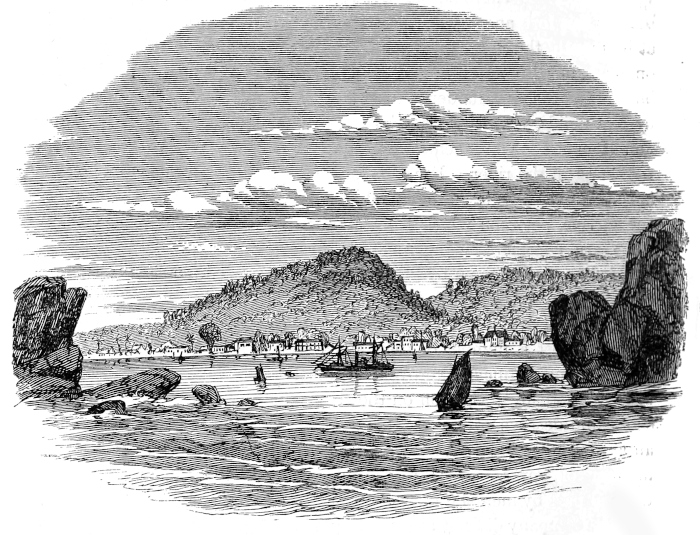

All danger past, we had an opportunity to look about us.

We were not more than two cable-lengths from a low sandy

shore, upon which was ranged, in a line parallel to the water,

a double row of houses, or rather huts, some built of boards,

but most of reeds, and all thatched with palm-leaves. Some

came down to the water, like sheds, and under one end were

drawn up pit-pans and canoes. Larger contrivances for navigating

24the San Juan river, resembling canal-boats, were also

moored close in shore, and upon each might be seen a number

of very long and very black legs, every pair of which

was surmounted by a very short white shirt. In the centre

of the line of houses, which was no other than the town of

San Juan de Nicaragua, was an open space, and in the middle

of this was a building larger than the others, but of like construction,

surrounded by a high fence of canes, and near one

end rose a stumpy flag-staff, and from its top hung a dingy

piece of bunting, closely resembling the British Union Jack;

and this was the custom-house of San Juan, the residence of

all the British officials; and the flag was that of the “King

of the Mosquitos,” the “ally of Great Britain!”

But of this mighty potentate, and how the British officials

came there, more anon. Just opposite us, on the shore,

was an object resembling some black monster which had

lost its teeth and eyes, and seemed sorry that it had left its

kindred at the Novelty Works. It was the boiler of a

steamer, which some adventurous Yankees had proposed

putting up here, but which, from some defect, had proved useless.

Behind the town rose the dense tropical forest. There

were no clearings, no lines of road stretching back into the

country; nothing but dense, dark solitudes, where the tapir

and the wild boar roamed unmolested; where the painted

macaw and the noisy parrot, flying from one giant cebia to

another, alone disturbed the silence; and where the many-hued

and numerous serpents of the tropics coiled among the

branches of strange trees, loaded with flowers and fragrant

with precious gums. The whole scene was unprecedentedly

novel and picturesque. There was a strange blending of objects

pertaining to the extremes of civilization. The boiler

of the steamer was side by side with the graceful canoe,

identical with that in which the simple natives of Hispaniola

brought fruits to Columbus; and men in stiff European costumes

were seen passing among others, whose dark, naked

27bodies, protected only at the loins, indicated their descent

from the aborigines who had disputed the possession of the

soil with the mailed followers of Cordova, and made vain

propitiations to the symbolical sun to assist them against

their enemies. Here they were, unknowing and careless

alike of Cordova or the sun, and ready to load themselves

like brutes, in order to earn a sixpence with which to get

drunk that night, in concert with the monotonous twanging

of a two-stringed guitar!

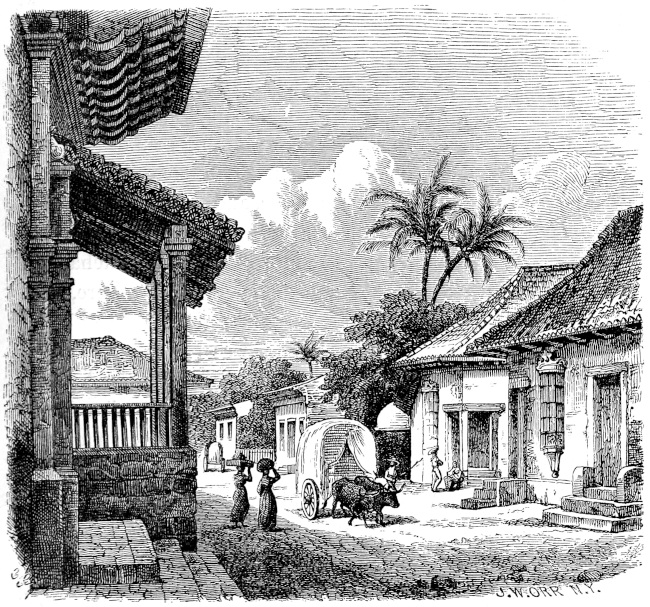

SAN JUAN DE NICARAGUA.—1849.

Our anchor was hardly down before a canoe came alongside,

containing as variegated an assortment of passengers as

can well be conceived. Among them were the officers of the

port, whose importance was made manifest from the numerous

and unnecessary orders they gave to the oarsmen, and

the prodigious bustle they made in getting up the side.

They looked inquiringly at the bright silken flag which one

of the party held in his hands, and which looked brighter

than ever under the rays of the setting sun. The eagles on

the caps of the party were also objects which attracted many

inquiring glances; and directly the captain was withdrawn

into a corner, and asked the significance of all this. The

answer seemed to diminish the importance of the officials

materially, and one approached, holding his sombrero reverently

in his hand, and said that “Her Britannic Majesty’s

Consul-General in Mosquitia, Mr. C——, was now resident

in the town, and that he should do himself the honor to

announce our arrival immediately, and hoped we had had a

pleasant voyage, and that we would avail ourselves of his

humble services;” to all of which gracious responses were

given, together with a drop of brandy, which last did not

seem at all unacceptable. I had warm letters of introduction

to several of the leading inhabitants of San Juan, and accordingly

began to make inquiries as to their whereabouts of a

respectable looking negro, who was amongst the visiting party.

To my first question, as to whether Mr. S—— S—— was

28then in town, the colored gentleman uncovered his head,

bowed low, and said the humble individual named was before

me. I also uncovered myself, bowed equally low, and

assured him I was happy to make his acquaintance, delivering

my letter at the same time with all the grace possible

under the circumstances.

He glanced over its contents, took off his hat again, and

bowed lower than before. Not to be behindhand in politeness,

I went through the same performance, which was responded

to by a genuflection absolutely beyond my power

to undertake, without risk of a dislocation; so I resigned the

contest, and gave in “dead beat,” much to the entertainment

of the Irish mate, who was not deficient in the natural

antipathy of his race towards the negro. Ben, my colored

servant, next received a welcome not less cordial than my

own; and my new acquaintance “was glad to inform me,

that fortunately there was a new house under his charge,

which was then vacant, and that he was happy in putting it

at my disposal.” The happiness was worth exactly eight

dollars, as I discovered by a bill which was presented to me

four days thereafter, as we were on the point of leaving for

the interior; and which, considering that the usual rent of

houses here is from four to five dollars per month, was probably

intended to include pay for the genuflections on shipboard.

We were impatient to land, and could not wait for

the yawl to be hoisted over the side; so we crowded ourselves

into the canoe of the “Harbor Master,” and went on

shore.

The population of the town was all there, many-hued and

fantastically attired. The dress of the urchins from twelve

and fourteen downwards, consisted generally of a straw hat

and a cigar, the latter sometimes unlighted and stuck behind

the ear, but oftener lighted and stuck in the mouth; a costume

sufficiently airy and picturesque, and, as B—— observed,

“excessively cheap.”

29Most of the women had a simple white or flowered skirt

(nagua) fastened above the hips, with a “guipil” or sort of

large vandyke, with holes, through which the arms were

passed, and which hung loosely down over the breast. In

some cases the guipil was rather short, and exposed a dark

strip of skin from one to four inches wide, which the

wanton wind often made much broader. It was very clear

that false hips and other civilized contrivances had not

reached here, and it was equally clear that they were not

needed to give fullness to the female figures which we saw

around us. All the women had their hair braided in two

long locks which hung down behind, and which gave them

a school-girly look quite out of keeping with the cool, deliberate

manner in which they puffed their cigars, occasionally

forcing the smoke in jets from their nostrils. Their feet

were innocent of stockings, but the more fashionable ladies

wore silk or satin slippers, which (it is hoped our scrutiny

was not indelicately close) were quite as likely to be soiled on

the inside as the out. A number had gaudy-colored rebosos

thrown over their heads, and altogether, the entire group,

with an advance-guard of wolfish, sullen-looking curs, was

strikingly novel, and not a little picturesque. We leaped

ashore upon the yielding sand with a delight known only to

the voyager who has been penned up for a month in a small,

uncomfortable vessel, and without further ceremony passed

through the crowd of gazers, and started down the principal

avenue, which, as we learned, had been called “King street”

since the English usurpation. The doors of the various

queer-looking little houses were all open, and in all of them

might be seen hammocks suspended between the front and

back entrances, so as to catch the passing current of air. In

some of these, reclining in attitudes suggestive of most

intense laziness, were swarthy figures of men, whose constitutional

apathy not even the unwonted occurrence of the

arrival, at the same moment, of two ships could disturb. The

30women, it is needless to say, were all on the beach, except a

few decrepit old dames, who gazed at us from the door-ways.

Passing through the town, we entered the forest, followed by

a train of boys and some ill-looking, grown-up vagabonds.

The path led to a beautiful lagoon, fenced in by a bank of

verdure, upon the edges of which were a number of women,

naked to the waist, who had not yet heard the news; they

were washing, an operation quite different from that of our

own country, and which consisted in dipping the clothes in

the water, placing them on the bottom of an old canoe, and

beating them violently with clubs. Visions of buttonless

shirts rose up incontinently in long perspective, as we turned

down a narrow path which led along the shores of the lagoon,

and invited us to the cool, deep shades of the forest. A flock

of noisy paroquets were fluttering above us, and strange fruits

and flowers appeared on all sides. We had not gone far

before there was an odor of musk, and directly a plunge in

the water. We stopped short, but one of the urchins waved

his hand contemptuously, and said “Lagartos!” And sure

enough, glancing through the bushes, we saw two or three

monstrous alligators slowly propelling themselves through

the water. “Devils in an earthly paradise!” muttered

B——, who dropped into the rear. The urchins noticed

our surprise, and by way of comfort, a little naked rascal in

advance observed, looking suspiciously around at the same

time, “Muchas culebras aqui,”—“Many snakes here!” This

interesting piece of intelligence opened conversation, and we

were not long in ascertaining that but a few days previously,

two men had been bitten by snakes, and had died in frightful

torments. It was soon concluded that we had gone far

enough, and that we had better defer our walk in the woods

to another day. It is scarcely necessary to observe, that it

was never resumed.

Returning, we met my colored friend, who informed me

that there was a quantity of hides stored in the house selected

31for my accommodation, but that he would have them removed

that evening, and the house ready for our reception in the

morning. Regarding ourselves as guests, whom it became

to assent to whatever suggestion our host might make, we

answered him that the arrangement was perfectly satisfactory,

that we could sleep that night comfortably on board the

vessel—a terrible fib, by the way, for we knew better—and

that he might take his time in making such provision for us

as he thought proper. We then sauntered through the

town, looking into the door-ways, catching occasional glimpses

of the domestic economy of the inhabitants, and admiring

not a little the perfect equality and general good understanding

which existed between the pigs, babies, dogs, cats, and

chickens. The pigs gravely took pieces of tortillas from the

mouths of the babies, and the babies as gravely took other

pieces away from the pigs. B—— observed that this was

as near an approach to those millennial days when the lion

and the lamb should lie down together as we should probably

live to see, and suggested that a particular “note” should be

made of it for the comfort of Father Miller and the Second-Advent

Saints in general. There was one house in which

we noticed a row of shelves containing sundry articles of

merchandise, among which long-necked bottles of various

pleasant hues were most conspicuous, and in front of which

was a rude counter, behind which again was a short lady of

considerably lighter complexion than the average, to whom

our colored friend tipped his hat gallantly, informing us at

the same time that this was the “Maison de Commerce de

Viscomte A. de B—— B—— et Co.;” the “Et Co.” consisting

of the Viscomte’s wife, two sons, and five daughters,

whose names all appeared in full in the Viscomte’s circulars.

Had we been told that here was the residence of some cazique

with an unpronounceable name, we might have thought the

thing in keeping, and passed on without ceremony; but a

Viscomte was not to be treated so lightly, and we turned

32and bowed profoundly to the short lady behind the counter,

who rose and courtesied with equal profundity.

We reached the beach just as the sun was setting, where

we found our mate with the yawl: “An’ it bates any city

ye’ve seen, I’ll be bound! It’s pier number one, is this

blessed spot of dirt where ye are just now; may be ye don’t

know it! And yonder hen-coop is the custom-house, be sure!

and that dirty clout is the Nagur King’s flag, bad luck to it!

and it’s meself who expects to live to see the stripes and forty

stars to back ’em, (divil a one less!) wavin’ here! Hurrah

for Old Zack!—an’ it’s him that can do it!”

It was clear that our mate, who had not looked at a bottle

during the whole voyage, thought a “d’hrap” necessary to

neutralize the miasma of San Juan.

“Perhaps ye know what ye’r laughing at, my dark boy;

an’ it’s meself that’ll be afther givin’ ye a taste of the way

we Yankees do the thing, savin’ the presence of his honor

here,” said the mate, dashing his hat on the ground, and

advancing a step toward my new acquaintance, who recoiled

in evident alarm. We interposed, and the mate cooled at

once, and shook hands cordially with the colored gentleman,

although he spoiled the amende by immediately going to the

water’s brink and carefully washing his palms.

While this scene was transpiring, a ghostly-looking individual,

wan with numberless fevers, approached us. He

was dressed in white, wore a jacket and a glazed cap, and

upon the latter, in gilded capitals, we read “Police.” He

took off his cap, bowed low, for he was used to it, and said

that Her Britannic Majesty’s Consul General presented his

respects to the gentlemen, regretted that, being confined to

his house by bodily infirmity, he could not wait on them in

person, and hoped that under the circumstances the gentlemen

would do him the favor to call upon him.

We responded by following the lead of the wan policeman

(there was only one other, the rest had run away,) who

33opened a wicket leading within the cane enclosure of the

custom-house, entered that building, and ascending a rough,

narrow, and ricketty flight of stairs, we were ushered into

what at home would be called a shocking bad garret, but

which were the apartments of Her Britannic Majesty’s Consul

General. A long table stood in the centre, and a couple of

candles flared in the breeze that came in at the unglazed

openings at either end of the apartment, giving a dim intermittent

light, by means of which, however, we succeeded in

discovering Mr. C——, the Consul General. He was reclining

on a rude settee, and rose with difficulty to welcome us. He

apologized for his rough quarters, betraying by his pronunciation

that his youth at least had been passed among the

haunted glens of Scotland. He had formerly been a member

of Parliament, and had been nearly a year on this coast, in a

service clearly little congenial to his feelings, and far from

being in accordance with his notions of honor and justice.

We found him intelligent and agreeable, and as free from

prejudices as a Briton could be, without ceasing to be a Briton

and a Scot.

The evening passed pleasantly, (“barring” the mosquitos,)

and though we were told of scorpions, which are often found

when people turn down their blankets, and of numerous

lizards, which insinuate themselves over night in one’s boots,

we were too glad to get on shore to be much alarmed by the

recital. Upon leaving, we were pressed to come every day

to the consulate to dine; for we were assured, and with truth,

that it was impossible to procure a reasonably decent meal

elsewhere in the town. The Nicaraguans at the fort above,

it was asserted, had bought up all the vegetables and edibles

intended for San Juan, having determined to starve the hated

English out, and there was not a foot of cultivated ground

within fifty miles; consequently the market was poorly supplied,

except with ship provisions, and of these we had had

quite enough. This was far from being comfortable, for we

34had expected to find at San Juan a profusion of all the productions

of the tropics, concerning which travellers had

written so enthusiastically; to be put, therefore, on allowances

of ship-biscuit and salt pork, was too much to permit

any consideration of delicacy, so we accepted Mr. C——’s

generous offer, returning on board to be phlebotomized

by a horde of barbarous mosquitos, and to get up next

morning feverish and unrefreshed, and only prevented from

appealing to the medicine-chest by the happy consciousness

that we were near the land.

The cook’s nondescript mess to which we had been treated

every morning since we left New York, and which had been

called by way of courtesy “breakfast,” was soon disposed of,

and we went on shore, where our colored friend received us

with a low bow, informing us at the same time that our house

was ready. He led the way to a building not far distant

from the “Maison de Commerce,” opening upon aristocratic

King street. It was constructed of rough boards, and was

elevated on posts, so that everybody who entered had to take

a short run and flying leap, and was fortunate if he did not

miss his aim and bark his shins in the attempt. It was satisfactory

to know that the structure was comparatively new,

and that the colonies of scorpions, lizards, house-snakes,

cockroaches, and the other numerous, nameless, and nondescript

vermin which flourish here, had not had time to multiply

to any considerable extent. And though there was a

large pile of tobacco in bales in one corner, with no other

object movable or immovable in the room, the novelty of

the thing was enough to compensate for all deficiencies, and

we ordered our baggage to be at once brought to the house.

By way, doubtless, of indicating the capacity of the structure,

our colored friend told us that this had been the headquarters

of a party of Americans bound for California for the space

of six weeks, and that forty of the number had contrived to

quarter here; a new and practical illustration of the indefinite

35compressibility of Yankee matter, which surpassed all

our previous conceptions. Our friend had provided for us

in other ways, and had engaged a place where we might

obtain our breakfasts, and proposed to introduce us to the

family which was to furnish that important meal. The

house was close by, and we were collectively and individually

presented to Monsieur S——, who had been a grenadier

under Napoleon, had served in numerous campaigns, had

been in many bloody battles, and had probably escaped being

shot because he was too thin to be hit. We were also introduced

to the spouse of Monsieur S——, who was the very

reverse of her lord, and who gave us a very good breakfast

and superb chocolate, for which we paid only a dollar each

per day. It was a blessed thing for our exchequer that we

didn’t dine, sup, and lodge there! At the same place breakfasted

a couple of Spanish gentlemen, who had come out in

the schooner, with a valuable cargo of goods for the interior.

Our hostess certainly could not have had the heart to charge

them a dollar for breakfast, for they had heard of revolutions

and a terrible civil war in Nicaragua, and had been frightened

36out of their appetites. A “bad speculation” at the best

was before them, perhaps pecuniary ruin. We pitied them,

but our appetites did not suffer from sympathy.

The day was passed in receiving visits of ceremony,

arranging our new quarters, rigging hammocks, (which we

obtained, at but little more than twice their actual value, at

the “Maison de” Commerce of the Viscomte,) and dragging to

light and air our mildewed wardrobes. We thought of consigning

our soiled linen to the women at the lagoon; but the

sturdy blows of their clubs still sounded in our ears, and we

trusted to the future; but the future brought rough stones in

place of the smooth canoe!

That night we passed comfortably in our new quarters,

interrupted only by various droppings from the roof, which

the active fancies of sundry members of the party converted

into scorpions and other noxious insects. All slept, notwithstanding,

until broad daylight next morning, when every

one was roused by the firing of guns, and a great noise of

voices, apparently in high altercation, combined with the

cackling of hens, the barking of dogs, and the squealing of

pigs; a noise unprecedented for the variety of its constituent

sounds.

“A revolution, by Jove!” exclaimed M——, whose brain

was full of the news from the interior; “it has got here

already!”

The doors were nevertheless thrown open, and every unkempt

head was thrust out to discover the cause of the

tumult. The scene that presented itself passes description.

There was a mingled mass of men, women, and children,

some driving pigs and poultry, others flourishing sticks; here

a woman with a pig under one arm and a pair of chickens in

each hand; there an urchin gravely endeavoring to carry a

long-nosed porker, nearly as large as himself, and twice as

noisy; there a busy party, forming a cordon around a mother

pig with a large family, and the whole excited, swaying,

37screaming mass retreating before the two policemen in white,

each bearing a sword, a pistol, and a formidable looking

blunderbuss.

“They are driving out the poor people,” said M——; “it

is quite too bad!”

But the manner in which two or three old ladies flourished

their sticks in the faces of our wan friend and his companion,

betokened, I thought, anything but bodily fear. Still, the

whole affair was a mystery; and when the crowd stopped

short before our doors, and every dark visage, in which anger

and supplication were strangely mingled, was turned towards

us, each individual vociferating the while, at the top of his

voice, we were puzzled beyond measure. “Death to the

English!” was about all we could gather, until the wan policeman

came up and explained, under a torrent of vituperation,

that he and his companion were merely carrying into

effect a wholesome regulation which Her Majesty’s Consul

General had promulgated, to the effect that the inhabitants of

San Juan (which he called Greytown) should no longer allow

the pigs and poultry to roam at large, but should keep them

securely “cooped and penned,” under penalty of having

them shot by Her Majesty’s servants; and as the aforesaid

pigs and poultry had roamed at their will since the time

“the memory of man runneth not back thereto,” and as

there were neither coops nor pens, it was very clear that the

wholesome regulation could be but partially complied with.

A stout mulatto, behind the policeman, carried a pig and

several fowls, which had evidently met a recent and violent

end; and we had strong misgivings as to the manner in

which the various small porkers and chickens which we had

encountered at the consul’s table had been procured.

The pale policeman grew pathetic, and was almost moved

to tears when he said that, while in the performance of his

duty, he was assailed as we saw, and that all his explanations

were unregarded, and he was disposed to do as his companions

38had done—run away, and leave the town to the dominion

of the pigs and chickens.

The crowd, which had been comparatively quiet during

this recital, now broke out in reply, and gathering countenance

from the presence of the Americans, fairly hustled the

policemen into the middle of the street, and might have

treated them to a cold bath in the harbor, had they not been

recalled by the voice of the Viscomte, who mounted a block

and declaimed furiously, in mingled Spanish and French,

against the “perfidious English,” and talked of natural and

municipal rights in a strain quite edifying, and eminently

French. But as the Viscomte had been instrumental in

bringing the English there, he did not get much of our sympathy.

He had lost a pet pig that morning, which gave pith

to his speech; and we determined to pay our particular respects

to it that evening at the consul’s.

To the appeals made to us directly, we were, as became us,

diplomatically evasive; but the people were easily satisfied,

and late that night we were treated to a serenade, the pauses

of which were filled in with, “Vivan los Americanos del

Norte”Norte”; and next day the news was current that six American

vessels of war were on their way to San Juan to drive out

the English, whose effective force consisted of the wan policeman

and his equally wan companion! And the consul himself

did us the honor to hope that we had said nothing to

encourage the poor people in their perversity, for he almost

despaired of making them respectable citizens! They couldn’t

discern, he was sorry to say, their own best interests. We

might have suggested to him that circumstances here

were quite different from those which surrounded the little

towns of Scotland, and that which might be “good for the

people” in one instance, might be eminently out of place in

another; but then it was none of our business.

During the day we paid a visit to the other side of the

harbor, where some Mosquito Indians, who came down the

39coast to strike turtle, had taken up their temporary residence.

They were the most squalid wretches imaginable, and their

huts consisted of a few poles set in a slanting direction, upon

which was loosely thrown a quantity of palm leaves. The

sides were open, and altogether the structure must have cost

fifteen minutes’ labor. Under this shelter crowded a variety

of half-naked figures, begrimed with dirt, their faces void of

expression, and altogether brutish. They stared at us vacantly,

and then resumed their meal, which consisted of a

portion of the flesh of the alligator and the manitus, chopped

in large pieces and thrown into the fire until the outer portions

were completely charred. These were devoured without

salt, and with a wolfish greediness which was horrible to

behold. At a little distance, away from the stench and filth,

the huts, with the groups beneath and around them, were

really picturesque objects.

One hut had been vacated for the moment; against it the

fishing-rods and spears of its occupants were resting, and in

front a canoe was drawn up; this attracted our particular

notice, and I had a sketch made of it on the spot. As we

40paddled along the shore, we saw many thatched huts in cool,

leafy arbors, surrounded by spots of bare, hard ground, fleckered

with the sunlight, which danced in mazes as the wind

waved the branches above. Around them were dark, naked

figures, and before them were light canoes, drawn close to

the bank, filling out the foreground of pictures such as

we had imagined in reading the quaint recitals of the early

voyagers, and the effects of which were heightened by the

parrots and macaws, fluttering their bright wings on the

roofs of the huts, and deafening the spectator with their

shrill voices. Occasionally a tame monkey was seen swinging

by his tail from the branches of the trees, and making

grimaces at us as we passed.

The habits of the natives were unchanged in the space of

three hundred years; their dwellings were the same; the

scenes we gazed upon were counterparts of those which the

Discoverers had witnessed. Eternal summer reigned above

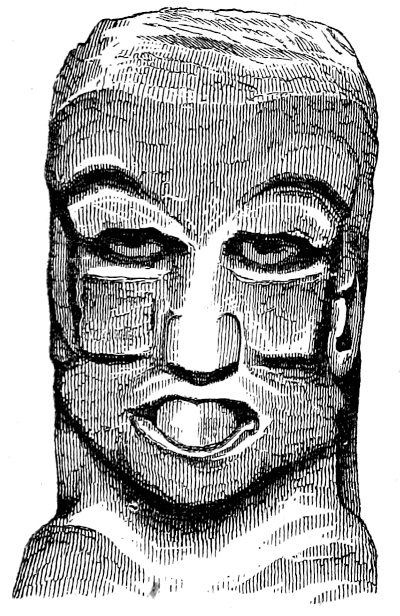

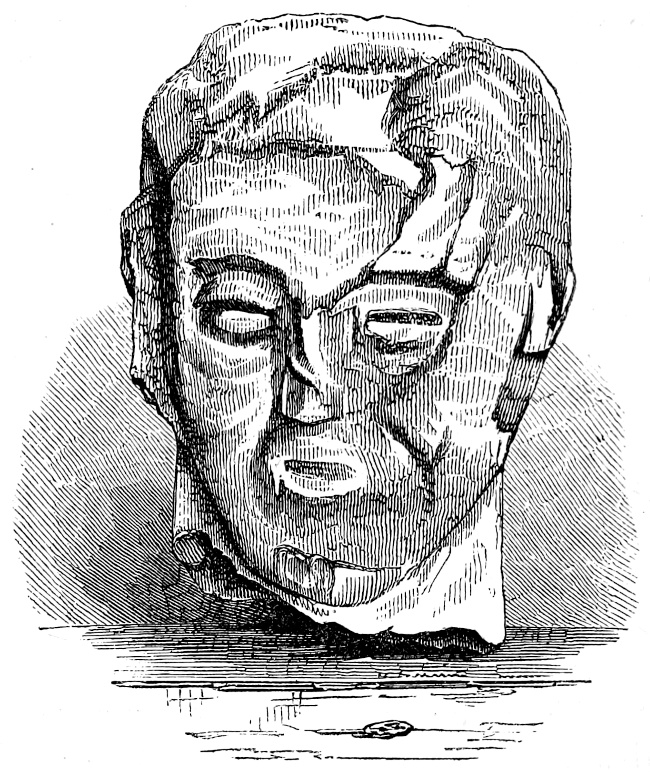

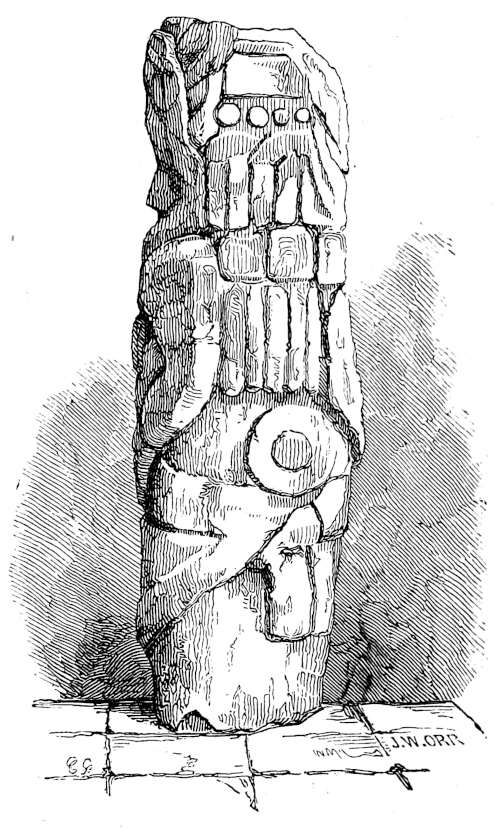

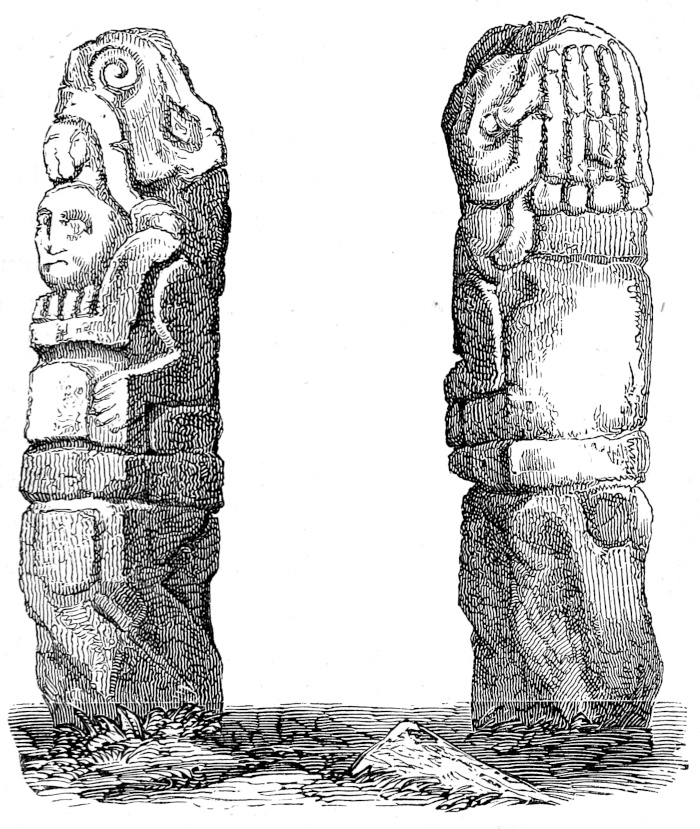

them; their wants were few and simple, and profuse nature